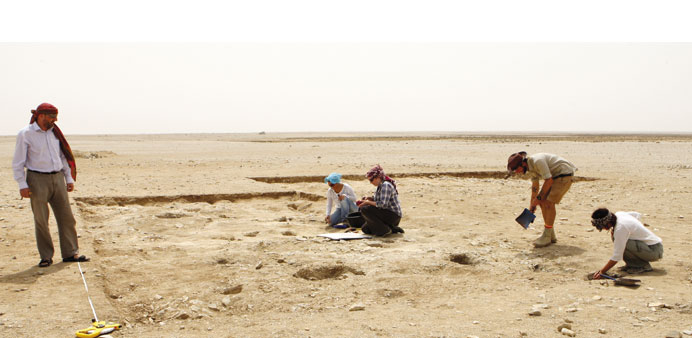

Spencer (second right) and other members of the excavation team at work on the Wadi Debayan archaeological site as Cuttler looks on. PICTURE: Shaji Kayamkulam.

By Bonnie James/Deputy News Editor

A number of “fantastic finds” have been reported from the recently-completed season of archaeological excavation at Qatar’s oldest settlement Wadi Debayan, which had human occupation dating back to 7,500 years ago.

“These include a piece of 6,800-year-old Ubaid pottery from southern Mesopotamia, evidence for structural remains and bone needles,” Qatar National Historic Environment Record (QNHER) Project co-director Richard Cuttler told Gulf Times.

The exploration of Wadi Debayan, is conducted under the QNHER Project, being developed as part of a joint initiative between the Qatar Museums Authority under the guidance of Faisal al-Naimi (head of antiquities) and the University of Birmingham, where Cuttler is a research fellow.

Gulf Times had reported recently that a total of four previously unknown burials, dated over 5,000 years ago, were found at the historic location, situated on the northwestern side of Qatar to the south of the site of Al Zubara and the Rá’s ‘Ushayriq peninsula.

One of the earliest Neolithic-Chalcolithic sites in the Gulf, Wadi Debayan has beneath its surface some of the earliest known structures in Qatar, and is one of only a few known sites of this period.

The extent of human inhabitation was revealed during the summer of 2011 when radiocarbon samples from different parts of the site demonstrated extended periods of occupation between 7,500 and 4,500 years ago. It is still unclear if this represents the same people or if occupation was continuous or seasonal.

“In northern Qatar there are two main wadis, Wadi Al Jalta on the eastern side, which comes out at Al Khor, and Wadi Debayan on the northwest, which comes out close to Al Zubara. Both of these were important to the Neolithic groups here,” Cuttler explained.

Although they were located quite a distance apart, there are lot of similarities between the two wadis as they were both exploited by Neolithic groups. They were using pottery from southern Mesopotamia, and also Obsidian, which is a kind of “volcanic glass” that has been source-matched to Turkey and is evidence for trade routes over 6,000 years ago that spanned a distance of more than 3,000km.

“So far we have opened up an area of approximately 15m by 15m and within that there are evidences for activities of many hundreds of years. We have got about 700 to 800 years of occupation. As the sea level dropped we can see that the occupation has shifted to other areas within the wadi,” he said.

Peter Spencer, site supervisor for the excavation area, observed that the recently-completed season’s focus was on understanding prehistoric activity across the entire landscape of Wadi Debayan.

“This year we unexpectedly found evidence for structural remains, down in the bottom of a trench, from the earliest phases of activity. We got bone needles, sharp enough, for net mending or could have been used for composite fish hooks,” he said.

The Ubaid pottery found this season is part of a dish, which probably would have been about 25cm across and fairly flat. “It has a got a typical green fabric with a black decoration on the inside and it is from Southern Mesopotamia, again indicative of the trade and the connections of that period,” Cuttler maintained.

One of many questions the archaeologists are hoping to resolve is what the inhabitants of Wadi Debayan were trading with southern Mesopotamia? It could be perishable items such as dried fish, or quite possibly, pearls.

“Here we have not found evidence of pearling, but pearls with holes drilled through them have been recovered from other Ubaid sites in the Gulf. We would love to find a pearl here. Every single bucketful of excavated material from Wadi Debayan is sieved,” said Emma Tetlow, the environmental manager for the project.

The team is looking for pearls, small beads made from drilled shells and also otoliths, which look like small stone flakes and are from the inner ears of fish. They have a very distinctive shape and are very indicative of the type of fish. An otolith can be sectioned to show growth rings that indicate approximate age and sometimes the season in which the fish has been caught.

“We have got some great information from the shells, molluscs, giving information about the different environments they were exploiting, because further into the Wadi there were intertidal environments, while there was deeper water at the mouth,” Tetlow explained.

Otolith examinations can reveal what kinds of fish the Wadi Debayan residents were exploiting in deeper and shallower water, and hopefully shed more light on whether they were staying on a seasonal basis or all year round, she added.