|

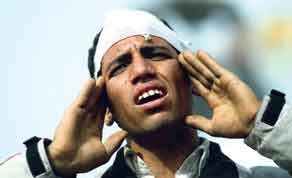

| An injured anti-government protester prays near Tahrir Square in Cairo yesterday |

Young and old, rich and poor, a vast swathe of society demanding veteran President Hosni Mubarak’s ouster came to pray and remember the “martyrs” of clashes that rocked the protest epicentre on Wednesday and Thursday.

The mood had changed in the crowd of tens of thousands, although many men nursed still-bloody wounds or lay exhausted on damp patches of grass, newspapers covering their faces from the Cairo sunshine.

Queues stretched hundreds of metres along a bridge across the Nile, protesters’ cuts stitched up and anger unbowed as they waited to be frisked and have their IDs checked, first by troops and then by protest organisers.

Two of Islam’s five daily prayers were held at once, a special measure that can be taken during time of “jihad” (holy war) or when travelling.

Worshippers used newspapers, banners or even Egyptian flags as impromptu prayer mats, reciting the traditional prayer for the dead for the more than 300 people who have died, according to UN figures, since daily protests erupted.

Many struggled to prostrate properly because of their injuries.

“We were born free and we shall live free,” prayer leader Khaled al-Marakbi said in his sermon. “I ask of you patience until victory.”

Marakbi sobbed gently, as did many others in the vast open-air congregation, still shaken by two days of clashes with Mubarak’s supporters that killed at least eight and injured over 800.

As soon as the prayers were finished, the crowd stood up and repeatedly shouted as one: “Down, down with Hosni Mubarak.”

The one thing which demonstrators said they want is for 82-year-old Mubarak to end the 30 years of his regime in the Arab world’s most populous nation, indelibly marked by corruption, police torture and lack of civil rights.

As on previous days, protesters approached foreign journalists on the square to tell them that the West should not fear the Muslim Brotherhood coming to power, insisting Egypt’s is a popular, classless and secular revolution.

“It’s not about what I want, it’s about what everybody wants, for Mubarak to go,” said Ragab, the owner of an advertising agency who joined the protest with his son Ammar, 14.

“Any person can be president, a woman, a Muslim, a Copt, but we want the system out.”

The crowd united again to sing the national anthem, before splitting into groups that milled around the square, shouting their anger at Mubarak’s regime through megaphones.

Rumours swirled that more pro-regime militants were being hired to attack the protesters who have been in the square since January 25.

“I am here to defend my brothers who were killed, they were innocent,” said Israa, a 20-year-old student, wearing a headscarf. “It is an honour to be here. I am not afraid to be killed. I will stay until he goes.”

Nearby, some of the sandstone rocks that served as weapons in the clashes had almost been ground to dust by the feet of the thousands who came to pray. But many stones remained, ready for the next battle.