Loyalty has been a driving force in the success of South Korea’s family-run “chaebol” conglomerates, but it can also shield the failings of its corporate culture and on Friday was linked to tragedy at the Lotte Group, the subject of a sweeping criminal probe.

Hours before group vice chairman Lee In-won was to be questioned by prosecutors, he was found dead in an apparent suicide, leaving a note hailing his boss as a “great man” and denying the company operated a slush fund, reportedly one of a list of prosecutors’ suspicions that includes embezzlement, tax evasion and breach of trust.

A prosecution spokesman could not immediately be reached for comment yesterday, and Lotte Group declined to comment except to say it was cooperating with prosecutors.

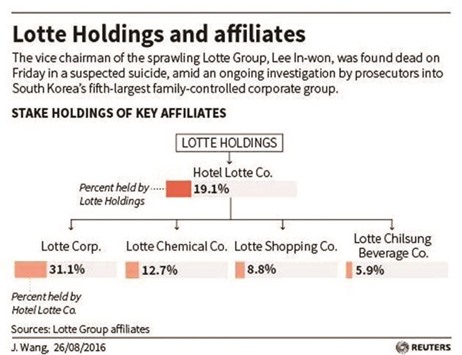

Prosecutors have since June been investigating about a dozen units at the retail-to-chemicals conglomerate, South Korea’s fifth-largest, but it would not be the first time that Lotte and similar groups have fallen short of governance standards in Asia’s fourth-largest economy.

Many of the family conglomerates that dominate the economy have been penalised over the years for conduct that is symptomatic of opaque interlocking ownership structures that can mask improper behaviour, and the fierce loyalty that can allow lapses to go unchecked.

“Under a corporate culture where loyalty towards a boss and an organisation is the most important criteria for evaluation, a sound corporate governance structure cannot survive,” said Kim Sang-jo, a professor of economics at Hansung University.

The attachment of staff and executives to the chaebol is legendary, typically embodied in a career-long service of gruelling hours.

It could explain why the penultimate act of the 69-year-old Lee was to defend his chairman Shin Dong-bin and the company he served for 43 years.

And why, at the start of the probe, investigators discovered that Lotte employees had, apparently on their own initiative, begun deleting computer files, several people familiar with the matter told Reuters.

While many chaebol have taken steps to improve governance, South Korea has a long way to go to reform a corporate system that is a legacy of the country’s decades of breakneck economic growth after the 1950-53 Korean war, investors and analysts say.

The complex cross-shareholdings they developed are a big part of the problem and were evident in an earlier run-in Lotte had with authorities four years ago, when one of the same units now being probed was fined for “unfair support” of an affiliate.

Lotte Group has since slashed the number of cross-shareholdings from a staggering 95,033 in April 2014 to 67 at the end of 2015, but that is still more than any other chaebol, according to South Korea’s Fair Trade Commission.

Lee Kyung-mook, a professor at Seoul National University who with the deceased Lee co-headed a Lotte committee set up last year to improve its culture, said Lotte, like most chaebol, was hierarchical and less efficient than it could be.

“Lotte Group, which is more focused on domestic business than Samsung, has been a little bit late to transforming its corporate culture and bringing it to the global level,” said Lee, who has written a book on the Samsung Group, the country’s biggest conglomerate.

Shares in Korean chaebol still trade more cheaply than similar companies in the developed world on concerns about opaque ownership structures and weak governance, investors say.

But changing the culture is much harder than changing formal structures, especially in a country where transgressions have been both common and sometimes treated relatively lightly.

Over the years, the heads of the Samsung, Hyundai Motor, SK and Hanwha chaebol have been convicted of crimes but received suspended sentences and, later, presidential pardons.

As recently as this month, the ailing chairman of the CJ Group, the country’s 15th-largest chaebol, was granted a presidential pardon after being sentenced last year to two and a half years in jail for tax evasion and

embezzlement.

.