A surplus of liquefied natural gas contracted by Japan is set to peak in the next few years, creating the opportunity for the world’s largest buyer to redirect supply to burgeoning markets.

The Asian nation that uses roughly a third of the world’s super-cooled gas is contracted to buy 20mn tonnes more than it needs by 2020, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. That supply glut – equal to almost half of what Europe consumes in a year – will reach its biggest as lower prices begin spurring consumption in about 30 smaller countries including Jordan, Thailand and Singapore.

Japan’s projected LNG surplus is the result of new gas export projects starting up globally colliding with lower-than-expected domestic demand and as coal and renewable energy eat into the country’s use of gas-fired generation. The global glut that has benefited importers with lower prices and more choices, is also turning some oversupplied buyers into sellers.

“Japanese trading houses that are contracted to buy US LNG may have an opportunity to resell some excess cargoes to new markets,” said Maggie Kuang, an analyst with BNEF in Singapore. “These smaller markets are responding to domestic needs to increase electricity production, but the amount of LNG they import will be dictated by price and infrastructure capacity.”

Companies in Asia that are contracted for more than they can buy are now seeking ways to resell their supplies.

Japanese regulators are investigating the legality of so-called destination clauses, which are traditionally included in supply contracts and limit buyers’ resale options. China, which is also projected by BNEF to have a surplus, may be inspired to follow suit, according to BMI Research. Less than half of global supplies contracted as of last year are destination flexible, according to BNEF.

Excess supply for China, the world’s third-largest importer, will peak in 2018 and the country may seek to delay cargoes or request destination flexibility, particularly for projects in which Chinese companies have stakes, according to Kuang.

LNG’s price competitiveness may delay natural gas production in China where demand for the super-cooled fuel rose about twice as fast over the past year as demand for gas, according to Kerry Anne Shanks, an analyst at Wood Mackenzie Ltd in Singapore.

“A lot of domestic supply in China is not being produced as quickly,” Shanks said by phone. “LNG is just going to be a better option for buyers than more expensive pipeline or domestic production.”

Spot LNG in northeast Asia lost 14% to $8.30 per million British thermal units last week, according to Energy Intelligence’s online World Gas Intelligence report.

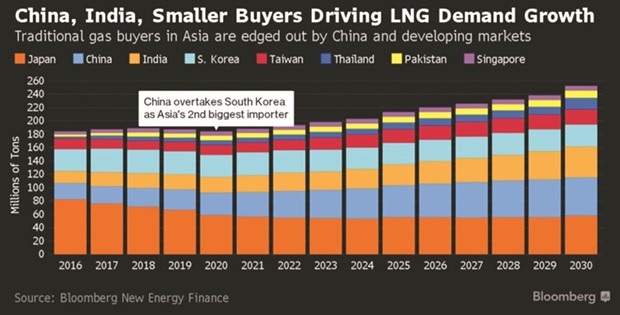

Meanwhile, countries that imported less than 5mn tonnes a year accounted for 19% of total consumption last year, up from 15% in 2014, according to BNEF. Those nations will account for 31% of global use by 2030, Kuang said.

Demand is seen rising to 422mn tonnes by 2030, almost two-thirds higher than last year, though the recent price crash has left about 250mn tonnes a year of supply projects shelved or delayed indefinitely.

That may set the stage for a coming deficit. Robust long-term demand growth prospects along with very few final investment decisions expected before 2020 pose a supply shortage risk which can drive up LNG prices after 2025, according to Kuang.