The man guiding Japan’s environment policy has a message for his country’s corporate titans - get ready because putting a price on carbon is all but inevitable if global warming is to be held at bay.

“Carbon pricing is one effective measure to create a low-carbon society,” Koichi Yamamoto, Japan’s environment minister, said in an interview this week. “This is the direction the world is going and Japanese companies should not misjudge the situation for their survival.”

Yamamoto, 69, wants to see a more robust debate in Japan over the merits of carbon pricing and its effectiveness at reducing greenhouse gas emissions without impeding economic development.

It’s a tricky balancing act rife with potential pitfalls. Australia’s Malcolm Turnbull almost torpedoed his political career in 2009 when he backed a rival’s emissions trading plan, while Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau may be facing legal action from the province of Saskatchewan over his government’s plan to introduce a carbon tax along with a cap-and-trade system for major industry.

In Japan, carbon pricing has pitted the environment ministry against the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, which sets the country’s energy and industry policies. The nation’s biggest business lobby, known as Keidanren, has also lined up to oppose placing a price on carbon, saying such a measure would impose “additional burdens” and would make Japanese companies less competitive internationally.

“Japanese businesses have been opposing explicit carbon pricing measures such as emission trading systems and carbon taxes in terms of securing equal footing in global business and strengthening corporate innovation,” Kiyoshi Tanigawa, manager of the environment and energy policy bureau at Keidanren, said by e-mail.

The merits and drawbacks of carbon pricing must be considered carefully, Yamamoto said, adding that Japan isn’t yet at a stage where discussions can be held on specifics such as whether a trading scheme or direct taxation would work best. The debate over carbon isn’t entirely new to Japan, nor are measures to place a price on greenhouse gases. In April 2010, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government introduced a cap-and-trade system targeting office buildings in Japan’s capital. The Japanese government had been planning to put in place emission trading of its own but the plan was suspended in December 2010 amid opposition from the nation’s industrial leaders.

Since that time, much of the world has moved on. Some 40 countries and another 20 subnational jurisdictions currently have a price on carbon either through a direct tax or a cap-and-trade system, according to a Bloomberg New Energy Finance report released in December. Meanwhile, China plans to introduce the first phase of a national trading scheme sometime this year. Mexico has begun adopting carbon-market rules similar to those in California.

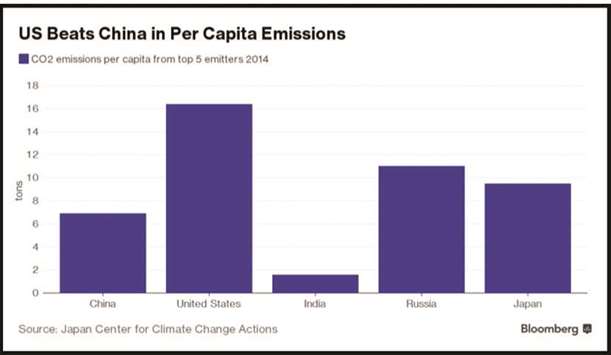

“We should study what works and what does not” in other countries that have introduced carbon pricing measures to take advantage of being a latecomer, Yamamoto said. To critics, Japan is a laggard on climate. Though the world’s third-largest economy is a signatory to the 2015 Paris Climate Accord, environmental groups and lobbyists say Japan’s commitments are weak. The nation ranked among the worst performers in an index comparing the emissions of 58 countries and measures to protect the climate in a recent report by Germanwatch and Climate Action Network Europe. “Japan is viewed about the same as Australia, an obstructionist and delayer of action, albeit for different reasons,” Tim Buckley, director of Energy Finance Studies at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, said by e-mail.

Yamamoto, who took charge of the ministry in August, has long been involved with environmental policy making. The minister, from the western prefecture of Ehime, was deputy to the head of the environment agency when Japan hosted an international conference in Kyoto in 1997 when a landmark agreement on climate change was reached.

Since becoming minister, Yamamoto has been vocal in raising concerns about coal-fired stations in Japan. Japanese power companies have plans at various stages of development to build more than 20 gigawatts of coal power, according to data compiled by Kiko Network, a Kyoto-based environmental group.

Yamamoto’s comment on coal-fired power and carbon come as Japan grapples with an increase in the use of fossil fuels such as coal and gas to make up for the lost nuclear capacity after the 2011 Fukushima disaster. Coal currently accounts for 31% of Japan’s power generation mix, while gas contributes 43%, according to London-based BNEF. The heavy reliance on fossil fuels threatens Japan’s commitment to reduce greenhouse gases by 26% by 2030 from 2013 levels and 80 percent by 2050.

“Gas is at least a better choice with half the emissions of coal,” Yamamoto said. “To pick coal just because it is a cheaper fuel is equal to throwing out attempts” to advance efforts to reduce emissions, Yamamoto said.

For those who see carbon capture and storage technology and so-called clean coal power generation systems as part of the answer to mitigating the production of greenhouse gases, Yamamoto is sceptical. “Even if you have systems with higher efficiency, the reduction in CO2 is only slight to the point where it’s meaningless,” he said.

In the end, though, Yamamoto’s views on coal must still contend with the trade ministry and backers of the fossil fuel who see it as the most cost-effective way to supply base-load power. While the environment minister can express an opinion on plans for new power stations as part of the process for environment impact assessments, the trade ministry has sole discretion to give building approval.

In April, the trade ministry issued its long-term strategies on climate change, saying that Japan isn’t at a stage where additional steps on carbon pricing are necessary given the measures the country already has in place and global carbon price levels.