Gerry Adams went from being the political voice of the Irish Republican Army, reviled by the British government and Northern Ireland’s Protestants, to playing the peacemaker in bringing the province’s Troubles to an end.

He handed over the reins of power of Sinn Fein yesterday to Mary Lou McDonald after having expressed satisfaction with his achievements in more than three decades of party service.

Adams has more recently become an anti-austerity figurehead and an opponent of Brexit while cultivating an avuncular image on Twitter.

It is a far cry from the bloodiest years of the sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland when he would defend the actions of paramilitaries and his voice was banned from British airwaves.

The bearded leader of the IRA’s political wing Sinn Fein was then a hated figure for many Protestants in Northern Ireland during the province’s three-decade long Troubles.

But he is credited with eventually convincing the IRA to give up their armed campaign to unite Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland.

More recently, he took centrestage after Britain voted for Brexit in 2016, throwing the peace accord into uncertainty with Northern Ireland set to leave the European Union, while the Republic of Ireland remains.

The outgoing leader labelled Brexit a “disaster” for the island of Ireland, and is still expected to be an influential voice as Britain and the EU negotiate over the border issue.

Born in Belfast on October 6, 1948, Adams came from a staunch republican background. His father was an IRA man who was jailed for eight years for his role in an ambush.

As a teenager, Adams became involved in the 1960s Catholic civil rights movement seeking to end discrimination favouring the pro-British Protestant majority.

He married Collette McArdle in 1971 and had one son, Gearoid, born two years later.

Adams was interned without trial in 1972 and 1973, in the early years of the Troubles — the 30 years of violence in which 3,500 people died.

He was charged with IRA membership in 1978 but the case was dropped due to insufficient evidence.

Adams always publicly said he was never an IRA member.

Malachi O’Doherty, author of Gerry Adams: An Unauthorised Life, told AFP: “He is committed to preserving the reputation of the IRA.”

O’Doherty believes Adams was an IRA member but was always “more politically than militarily inclined”.

Adams became Sinn Fein president in 1983 and was elected to the British parliament, though he never took his seat as he would not swear an oath of allegiance to the British head of state, Queen Elizabeth II.

“I think Guy Fawkes had the right attitude towards Westminster,” he said on his election, referring to the 17th-century Catholic plotter who tried to blow up parliament.

Adams was seriously wounded in a 1984 Loyalist paramilitary assassination attempt and often moved between safe houses. He was a regular face carrying coffins at IRA funerals and was seen in Britain as a pariah.

In 1988, Britain’s then prime minister Margaret Thatcher banned broadcasters from transmitting Adams’ voice in an effort to deny him the “oxygen of publicity”. The ban was lifted by Thatcher’s successor John Major in 1994.

After the election of British premier Tony Blair in 1997, Adams became a key figure in the peace talks which were enshrined in the landmark 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

He was widely seen as having played a key role in persuading the IRA to renounce its armed struggle in 2005, viewed as a turning point in the province’s history.

He sought to broaden Sinn Fein’s appeal in the Republic of Ireland and sat in the Dublin parliament from 2011.

The leftist faction went from four seats in 2007 to 23 out of 158 in 2016, becoming the republic’s third-biggest party.

In 2014, he was arrested and held for questioning for four days in connection with the IRA’s 1972 abduction and murder of Jean McConville, a mother-of-10 accused by the IRA of passing information to the British army.

A now-dead former IRA commander, in recorded interviews with a US university, had claimed Adams had ordered the killing but prosecutors found insufficient evidence to bring charges.

In more recent years, Adams developed a softer image.

In 2015, he shook hands with Britain’s Prince Charles on a visit to Ireland and the two had a private meeting. It was seen as a symbolic gesture of reconciliation. The IRA had killed the prince’s beloved great-uncle and mentor Lord Louis Mountbatten in 1979.

Adams himself said in a 1994 US television interview: “Making peace, I have found, is much harder than making war.”

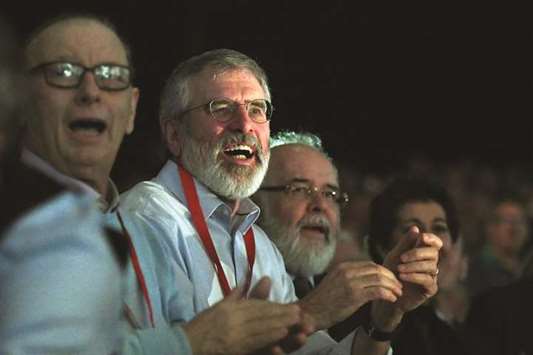

Sinn Fein’s Gerry Adams cheers for newly elected Sinn Fein president Mary Lou McDonald at a special party conference in Dublin yesterday.