The glut that decimated global natural gas prices may be vanishing just as US shale exports are surging.

The key: China, the world’s biggest energy user, is helping soak up supplies of liquefied natural gas with record demand in a switch to cleaner-burning fuel from coal. That boosted LNG prices even as new plants from the US to Australia use massive tankers to send cargoes across the high seas. And the profusion of projects may not be enough to slake demand.

The recovery comes at an opportune time for US producers, with the nation’s second export facility starting up this month and three more plants set to enter service next year. By 2022, the country will challenge Australia and Qatar for the top spot among exporters, according to the International Energy Agency. Executives from US LNG developers including Cheniere Energy and Tellurian were set to discuss the outlook for the fuel at the CERAWeek by IHS Markit conference in Houston yesterday.

“There is no LNG supply glut,” said Meg Gentle, chief executive officer at Tellurian, which is planning to build a terminal in Louisiana. Though demand surged last year, “‘the market could have been even larger, had more supply-side infrastructure been completed on time,” she said in an e-mail.

Worldwide oversupply was expected to weigh on the market into the 2020s, prompting export developers to consider cheaper, smaller-scale projects that would target emerging markets like the Middle East and Latin America.

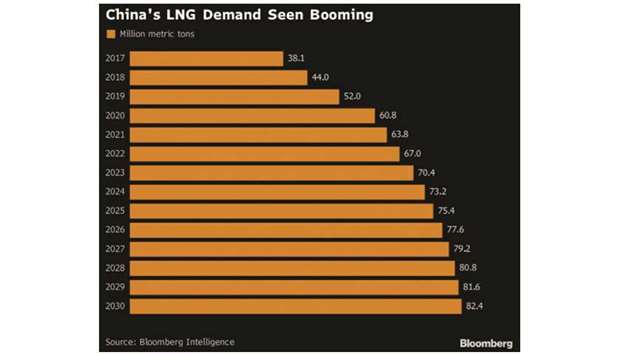

Then China came to the rescue. The nation’s LNG imports jumped 46% last year as it moved to curb pollution from coal. With demand from South Korea to India also on the rise, spot LNG prices in North Asia surged to the highest in three years. And by 2024, China’s imports could almost double from 2017, said Matthew Hong, director of research for power and gas at Morningstar Inc in Chicago, in a note to clients.

Another bullish factor: Though new export terminals are starting up, the list of projects facing delays is lengthening. Meanwhile, other proposals have stalled in recent years as investors balked amid concern that the gas glut would linger into the next decade.

Sempra Energy said in August that the startup of its Cameron LNG terminal in Louisiana had been pushed to 2019 from mid-2018, joining at least eight other US projects dealing with setbacks. The nation now has just two terminals - Cheniere’s Sabine Pass in Louisiana and Dominion Energy Inc’s Cove Point in Maryland - shipping overseas.

Because LNG plants tend to be massive, costly undertakings - Cove Point cost $4bn to convert from an existing import facility - they need long-term purchase agreements to secure financing. But as more supply hit the market, buyers sought flexible contracts and began shying away from the 20-year deals that had once been standard.

“Because buyers are aware of a lot of supplies coming on, they’re cognizant of pricing and we’re not seeing a lot of long-term contracts being signed,” Sam Margolin, an analyst at Cowen and Company in New York, said by telephone.

That creates a risk there won’t be enough LNG on the market to meet demand, according to ship broker Poten & Partners Inc. The average length of a supply contract fell to less than seven years in 2017, the lowest on record, Poten said. And in the last two years, only two new projects have moved forward.

“The construction of new capacity may lag demand growth and set the stage for tighter markets and higher prices in the future,” Jason Feer, head of business intelligence at Poten in Houston, said in a research note to clients.

By 2035, the LNG market will need at least 20 mega-projects to meet demand, Royal Dutch Shell has said. The shift to shorter-term deals isn’t without exceptions: For instance, Cheniere, the first US exporter of shale gas, last month signed the first long-term contract to supply LNG to China. In January, it inked a 15-year deal with the independent trading house Trafigura Group Pte Ltd. The boost in consumption has outpaced forecasts, said Andrew Walker, vice president of strategy and communication at Cheniere, in a phone interview. “Supply is visible, demand is less visible,” Walker said. But “demand continues to surprise to the upside.”

.