Nasa’s distant Voyager 2 probe has sent a “heartbeat” signal to Earth after mission control mistakenly cut contact, the US space agency said yesterday.

Launched in 1977 to explore the outer planets and serve as a beacon of humanity to the wider universe, it is currently more than 12.3bn miles (19.9bn km) from our planet – well beyond the solar system.

A series of planned commands sent to Voyager 2 on July 21 “inadvertently caused the antenna to point two degrees away from Earth”, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa)’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) said in a recent update.

This left it unable to transmit data or receive commands to its mission control – a situation that was not expected to be resolved until it conducted an automated re-orientation manoeuvre on October 15.

However, Voyager project manager Suzanne Dodd told AFP yesterday that the team enlisted the help of the Deep Space Network – an international array of giant radio antennas, plus a few that orbit Earth – in a last-ditch effort to re-establish contact sooner.

To their surprise, “this was successful in that we see the ‘heartbeat’ signal from the spacecraft”, she said. “So we know the spacecraft is alive and operating. This buoyed our spirits.”

However, while engineers can now see a heartbeat – in technical terms, the carrier wave associated with Voyager 2 – they can’t yet read the information signal that shapes the carrier wave, which conveys all the data collected by the spacecraft.

“We are now generating a new command to attempt to point the spacecraft antenna toward Earth,” Dodd added, although she said there is only a “low probability” it will work.

Still, given October 15 is a long way away, Nasa will keep trying to send up these commands.

While JPL built and operates Voyager spacecraft, the missions are now part of the Nasa Heliophysics System Observatory.

Voyager 2 left the protective magnetic bubble provided by the Sun, called the heliosphere, in December 2018, and is currently travelling through the space between the stars.

Before leaving our solar system, it explored Jupiter and Saturn, and became the first and so far only spacecraft to visit Uranus and Neptune.

Voyager 2’s twin Voyager 1 was mankind’s first spacecraft to enter the interstellar medium, in 2012, and is currently almost 15bn miles from Earth.

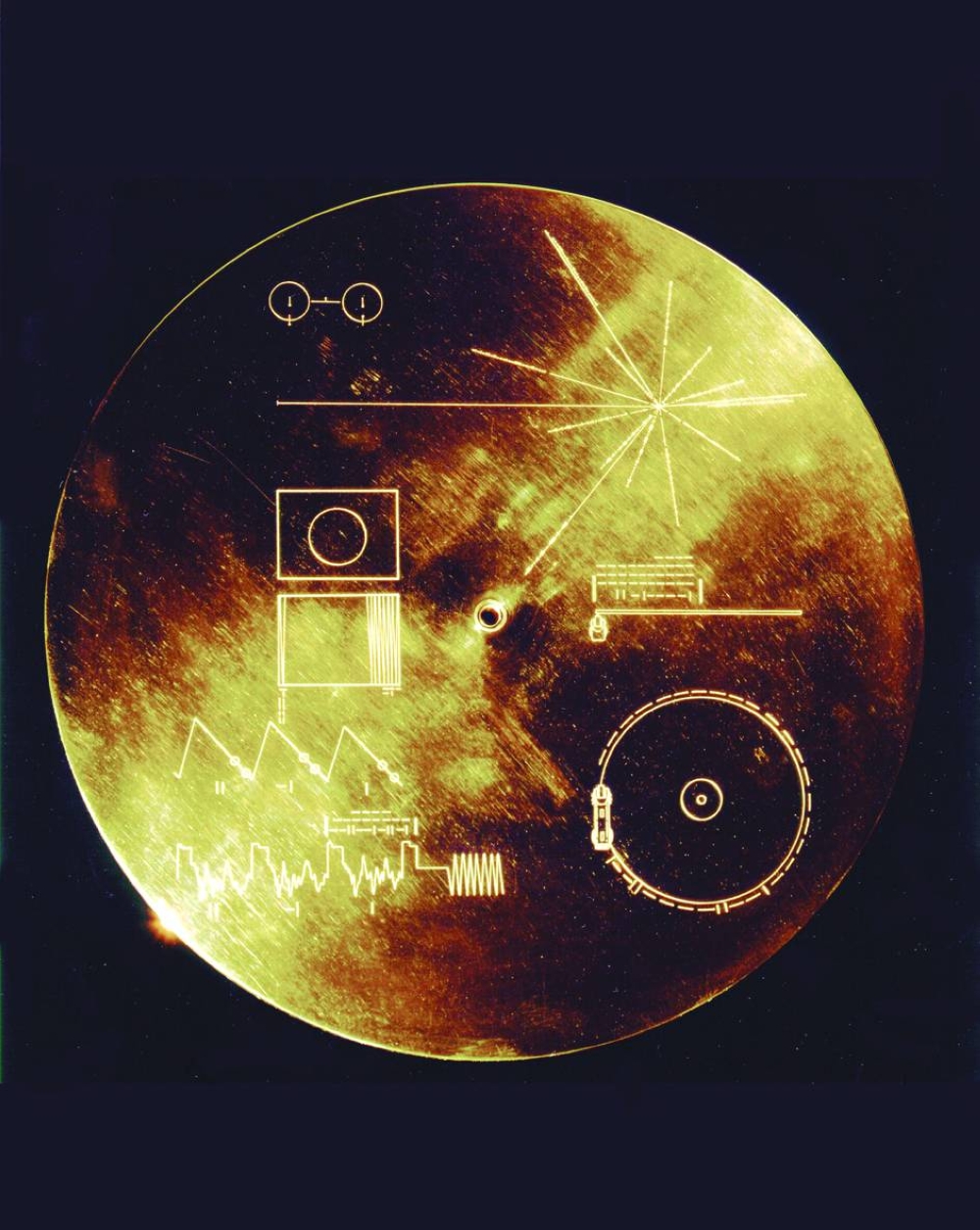

Both Voyager spacecraft carry “Golden Records” – 12”, gold-plated copper disks intended to convey the story of our world to extraterrestrials.

These include a map of our solar system, a piece of uranium that serves as a radioactive clock allowing recipients to date the spaceship’s launch, and symbolic instructions that convey how to play the record.

The contents of the record, selected for Nasa by a committee chaired by legendary astronomer Carl Sagan, include encoded images of life on Earth, as well as music and sounds that can be played using an included stylus.

For now, the Voyagers continue to transmit back scientific data, though their power banks are expected to be eventually depleted, sometime after 2025.

They will then continue to wander the Milky Way, potentially for eternity, in silence.

This 1977 Nasa file image shows a gold aluminium cover that was designed to protect the Voyager 1 and 2 Sounds of Earth gold-plated records from micrometeorite bombardment, but also serves a double purpose in providing the finder a key to playing the record.