The world’s top central bankers stressed the need to keep interest rates high until inflation is contained — and wrestled with deeper economic shifts that will make their jobs harder.

At an annual Federal Reserve gathering in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, keynote speeches from Fed Chair Jerome Powell and European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde on Friday laid out the challenges each is facing in deciding if they should extend historic strings of rate increases that began last year. At the same time, they offered investors few clues as to whether they would in fact do so in the coming months.

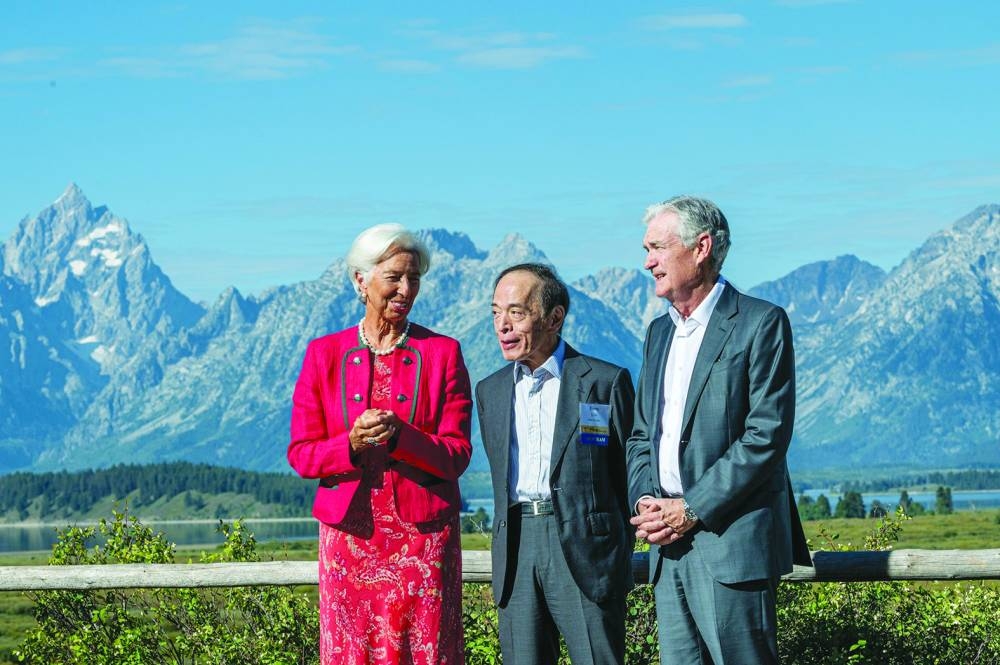

Appearing on a Saturday panel at the confab, hosted by the Kansas City Fed in the heart of Grand Teton National Park, Bank of England Deputy Governor Ben Broadbent said UK rates may have to rise further, while Bank of Japan Governor Kazuo Ueda reaffirmed the ongoing need for low rates there.

A key theme emerging from the formal conference proceedings and conversations on the sidelines was difficulties adapting to forces outside the control of monetary authorities. The attendees discussed topics including productivity and innovation, bond-market structure, global supply chains and rising public debt levels.

“These structural shifts we heard about, we all know they’re important. We all know they’re big. Central banks can’t do much about a lot of them,” said Kristin Forbes, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology economics professor and former Bank of England policymaker. “It does change the parameters of how you set monetary policy, which makes it just very hard to operate,” she added.

The Fed and ECB are engaged in similar debates over whether to raise borrowing costs at policy meetings next month, even as the US economy has surprised with its resilience while Europe’s seems to be headed for a downturn. Lingering inflation in both jurisdictions and uncertainty over how quickly it will recede is the common challenge.

Powell, in his speech, remained vague about whether the Fed would lift its benchmark rate again, though he warned that “additional evidence of persistently above-trend growth could put further progress on inflation at risk and could warrant further tightening of monetary policy.”

Lagarde, in her address and in a subsequent Bloomberg TV interview, was more wide-ranging in discussing the new landscape facing ECB policymakers, one characterised by novel challenges arising from historic changes, including the energy transition and a fragmentation of global trade into competing geopolitical blocs. She too, though, steered clear of speaking about decisions in the months ahead.

Powell’s and Lagarde’s colleagues, however, didn’t hesitate to weigh in on the cases for and against additional rate increases. In interviews, some — like Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester and Bank of Latvia Governor Martins Kazaks — argued it was better to err on the side of higher rates, which could be reversed if necessary.

Others, including Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker and Banco de Portugal Governor Mario Centeno, took the opposite side, arguing for a cautious approach as they assess the impact of previous hikes.

The resilience of the US economy has investors and economists debating whether the neutral rate of interest — where policy neither slows down nor accelerates the economy — has shifted higher. That would imply policymakers need to raise rates even further to curb inflation.

But despite speculation that Powell would use his highly anticipated speech to weigh in, the target didn’t come into question at the symposium, beyond the Fed chief reiterating that policymakers can’t identify the rate with certainty. It was a departure from last year, where some economists argued that developed economies were entering a new reality and so the target should be lifted to account for that.

Among the issues that did permeate discussions over the weekend was trade. A variety of factors have caused trade in many developed markets to move away from traditional partners such as China, to countries like Vietnam or Mexico. Some economists believe this “nearshoring” or “friendshoring” could add to inflationary pressures.

“When you start introducing these kinds of frictions, it’s going to make large segments of the economy less sensitive to monetary policy,” said Katheryn Russ, professor of economics at the University of California, Davis, who presented a discussion on a paper about supply chains.

Russ said these emerging trends in trade also make economies less resilient to non-geopolitical shocks and increase the need for stability through monetary policy. “There are really big challenges, I think, ahead for monetary policy if we and other countries continue to pursue this,” she said.

Policymakers also grappled with ballooning budget deficits, including their effect on Treasury market functioning. Market turmoil during the early days of the pandemic has added to policymakers’ and economists’ calls for reforms to infrastructure and regulations.

The prevailing sentiment in conversations and questions at this year’s symposium: a need for humility amid the uncertainty of the current landscape.

Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank; Kazuo Ueda, governor of the Bank of Japan; and Jerome Powell, Federal Reserve chairman, at the Jackson Hole economic symposium. A key theme emerging from the formal conference proceedings and conversations on the sidelines was difficulties adapting to forces outside the control of monetary authorities.