In his 2018 book Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy, venture investor William H Janeway highlights the US government’s pivotal role in spurring innovation by funding research and development in critical defence technologies. Despite the significant expenditure associated with these technological advances, the scale of America’s economic reach effectively drove down the costs of cutting-edge tech products and services. These innovations were subsequently commercialised through private entrepreneurship, making them easily accessible to consumers. Simply put, by harnessing economies of scale and specialisation, the US innovation economy ushered in an era of rapid growth and prosperity.

As China integrated into the global economy, it adopted a similar model, enabling Chinese companies to reduce the costs of new technologies such as solar panels, 5G infrastructure, and electric vehicles while building the country’s industrial and military capabilities. At the same time, China’s increasingly assertive foreign policy raised concerns among Democrats and Republicans in the United States.

By the time President Xi Jinping assumed power in 2012, the US already regarded China as its main geopolitical rival. Consequently, the US imposed sanctions on China in an effort to prevent American technology from enhancing Chinese military capabilities. Between August 2018 and June 2023, 669 Chinese companies were added to the Department of Commerce’s so-called Entity List, used to blacklist foreign companies on national-security grounds.

These sanctions have had a significant impact on China, exacerbating its ongoing economic slowdown and heightening the risk of deflation. With US allies such as The Netherlands, South Korea, and Japan imposing their own export restrictions, Chinese companies have been deprived of key inputs for the design and production of advanced semiconductors.

This strategy has resulted in a 17.9% decline in US-China trade during the first half of 2023. China’s share of US imports has plummeted to 13.3% during this period, a 38.4% drop from a peak of 21.6% in 2017. Foreign direct investment and portfolio flows have also decreased, with net FDI flows recording a deficit of $49bn in the second quarter of this year.

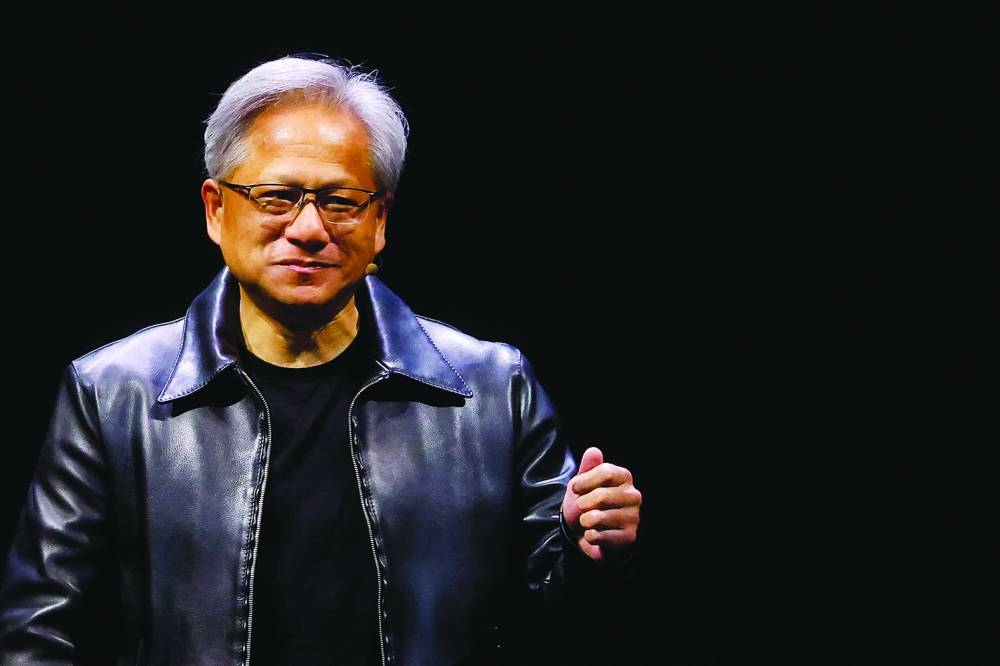

The ongoing process of deglobalisation will have profound implications for US economy as well. More than 70,000 US companies currently operate in China, and nearly 90% of them are profitable. China is the world’s largest semiconductor market, accounting for more than 31% of global sales and 36% of US semiconductor sales. For Intel and Nvidia, China represented, respectively, 27% and 26.4% of revenues in 2022, and a whopping 67.1% of Qualcomm’s revenues. “If we are deprived of the Chinese market, we don’t have a contingency for that,” Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang recently warned. “There is no other China, there is only one China.”

As the global innovation economy continues to fragment, Chinese and American companies will likely face higher costs for R&D and for manufacturing equipment. After all, as the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company and other semiconductor manufacturers have recently discovered, it is far more expensive to produce chips in the US than in Asia. Worse, governments worldwide will likely turn to industrial subsidies to compensate for the loss of the Chinese market, potentially triggering a harmful subsidy war.

Given that the US seems determined to continue with its current strategy of expanding sanctions, China is expected to retaliate with its own measures. Recent export restrictions on strategically vital raw materials such as germanium, gallium, tungsten, and rare earth metals foreshadow the possibility of more wide-ranging measures. As the International Monetary Fund has warned, “a fragmented world is likely to be a poorer one.”

Moreover, dividing the global technology and innovation market into two distinct categories – one for defence purposes and the other encompassing everything else – could distort the incentives for technological development. Given that all technology has potential military applications, the interplay between restrictions and subsidies could steer innovation toward national security, potentially impeding the emergence of consumer-oriented high-tech products and services.

Just as regulation is necessary to curb market concentration and address the ethical implications of generative AI and biotech, competition in defence-oriented technologies must be carefully controlled. Even at the height of the Cold War, the US and the Soviet Union successfully negotiated treaties that effectively slowed the nuclear arms race and prevented mutual assured destruction.

Similarly, the US and China must establish a transparent rules-based framework that facilitates private-sector participation in open trade, fosters trust, ensures market openness, protects property rights, and sets boundaries on punitive sanctions. State-imposed sanctions and subsidies will inevitably push the private sector and markets into retreat, with adverse consequences for the world economy. This has been a topic of fierce debate within China over the past few years, as the state’s role in the economy expanded.

To be sure, China and the US each want to bargain from a position of strength, and both are understandably concerned that initiating negotiations might be perceived as a sign of weakness. Consequently, it is possible that only the pain of a severe global recession can compel them to start talking. Nevertheless, the longer these talks are delayed, the greater the suffering will be for China, the US, and the rest of the world. — Project Syndicate

- Andrew Sheng is a distinguished fellow at the Asia Global Institute at the University of Hong Kong.

- Xiao Geng, Chairman of the Hong Kong Institution for International Finance, is a professor and Director of the Institute of Policy and Practice at the Shenzhen Finance Institute at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen.