Part of the answer is economic: neoliberalism simply did not deliver what it promised. In the US and other advanced economies that embraced it, per capita real (inflation-adjusted) income growth between 1980 and the Covid-19 pandemic was 40% lower than in the preceding 30 years.

Worse, incomes at the bottom and in the middle largely stagnated while those at the very top increased, and the deliberate weakening of social protections has produced greater financial and economic insecurity.

Rightly worried that climate change jeopardises their future, young people can see that countries under the sway of neoliberalism have consistently failed to enact strong regulations against pollution (or, in the US, to address the opioid crisis and the epidemic of child diabetes). Sadly, these failures come as no surprise. Neoliberalism was predicated on the belief that unfettered markets are the most efficient means of achieving optimal outcomes. Yet even in the early days of neoliberalism’s ascendancy, economists had already established that unregulated markets are neither efficient nor stable, let alone conducive to generating a socially acceptable distribution of income.

Neoliberalism’s proponents never seemed to recognise that expanding the freedom of corporations curtails freedom across the rest of society. The freedom to pollute means worsening health (or even death, for those with asthma), more extreme weather, and uninhabitable land. There are always tradeoffs, of course; but any reasonable society would conclude that the right to live is more important than the spurious right to pollute.

Taxation is equally anathema to neoliberalism, which frames it as an affront to individual liberty: one has the right to keep whatever one earns, regardless of how one earns it. But even when they come by their income honestly, advocates of this view fail to recognise that what they earn was made possible by government investment in infrastructure, technology, education, and public health.

Rarely do they pause to consider what they would have if they had been born in one of the many countries without the rule of law (or what their lives would look like if the US government had not made the investments that led to the Covid-19 vaccine).

Ironically, those most indebted to government are often the first to forget what government did for them.

Where would Elon Musk and Tesla be if not for the near-half-billion-dollar lifeline they received from president Barack Obama’s department of energy in 2010? “Taxes are what we pay for civilised society,” the Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes famously observed. That hasn’t changed: taxes are what it takes to establish the rule of law or provide any of the other public goods that a twenty-first-century society needs to function.

Here, we go beyond mere tradeoffs, because everyone – including the rich – is made better off by an adequate supply of such goods. Coercion, in this sense, can be emancipatory. There is a broad consensus on the principle that if we are going to have essential goods, we have to pay for them, and that requires taxes.

Of course, advocates of smaller government would say that many expenditures should be cut, including government-managed pensions and publicly provided healthcare. But, again, if most people are forced to endure the insecurity of not having reliable health care or adequate incomes in old age, society has become less free: at a minimum, they lack freedom from the fear of how traumatic their future might be. Even if multibillionaires’ well-being would be crimped somewhat if each were asked to pay a little more in taxes to fund a child tax credit, consider what a difference it would make in the life of a child who doesn’t have enough to eat, or whose parents cannot afford a doctor’s visit. Consider what it would mean for the whole country’s future if fewer of its young people grew up malnourished or sick.

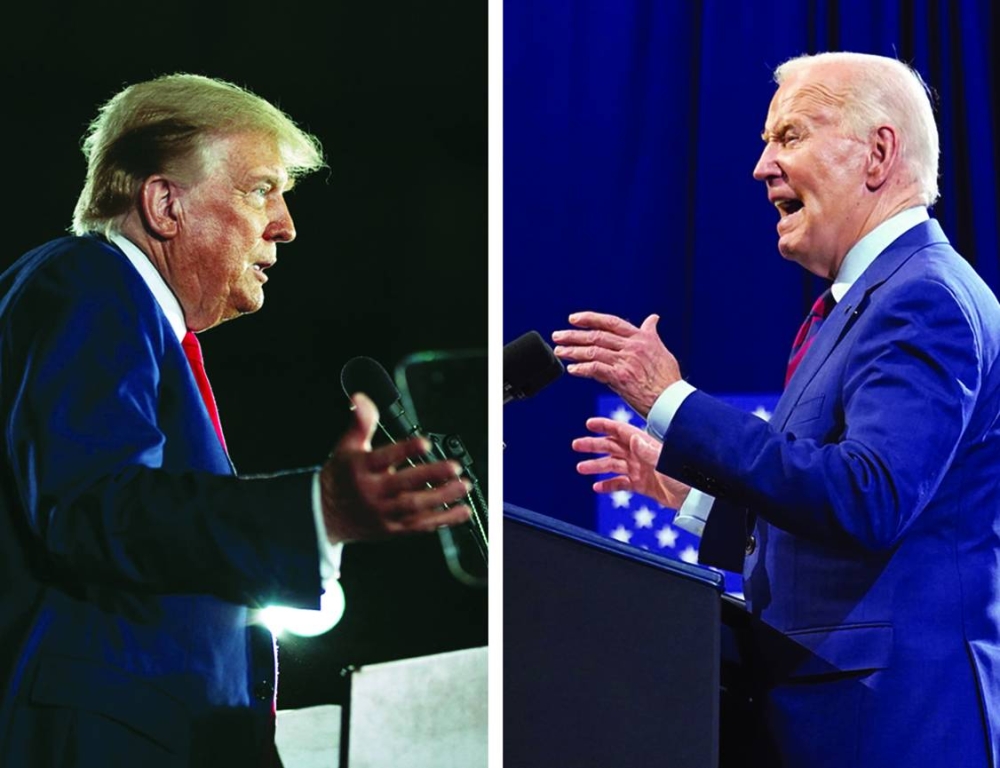

All these issues should take centre stage in this year’s many elections. In the US, the upcoming presidential election offers a stark choice not only between chaos and orderly government, but also between economic philosophies and policies. The incumbent, Joe Biden, is committed to using the power of government to enhance the well-being of all citizens, especially those in the bottom 99%, whereas Donald Trump is more interested in maximising the welfare of the top 1%. Trump, who holds court from a luxury golf resort (when he is not in court himself), has become the champion of crony capitalists and authoritarian leaders around the world.

Trump and Biden have vastly different visions of the kind of society we should be working to create. In one scenario, dishonesty, socially destructive profiteering, and rent-seeking will prevail, public trust will continue to crumble, and materialism and greed will triumph; in the other, elected officials and public servants will work in good faith toward a more creative, healthy, knowledge-based society built on trust and honesty.

Of course, politics is never as pure as this description suggests. But no one can deny that the two candidates hold fundamentally different views on freedom and the makings of a good society. Our economic system reflects and shapes who we are and what we can become. If we publicly endorse a selfish, misogynistic grifter – or dismiss these attributes as minor blemishes – our young people will absorb that message, and we will end up with even more scoundrels and opportunists in office. We will become a society without trust, and thus without a well-functioning economy.

Recent polls show that barely three years after Trump left the White House, the public has blissfully forgotten his administration’s chaos, incompetence, and attacks on the rule of law. But one need only look at the candidates’ concrete positions on the issues to recognise that if we want to live in a society that values all citizens and strives to create ways for them to live full and satisfying lives, the choice is clear.

- Joseph E Stiglitz, a former chief economist of the World Bank and former chair of the US President’s Council of Economic Advisers, is university professor at Columbia University, a Nobel laureate in economics, and the author, most recently, of The Road to Freedom: Economics and the Good Society (W. W. Norton & Company, Allen Lane, 2024).