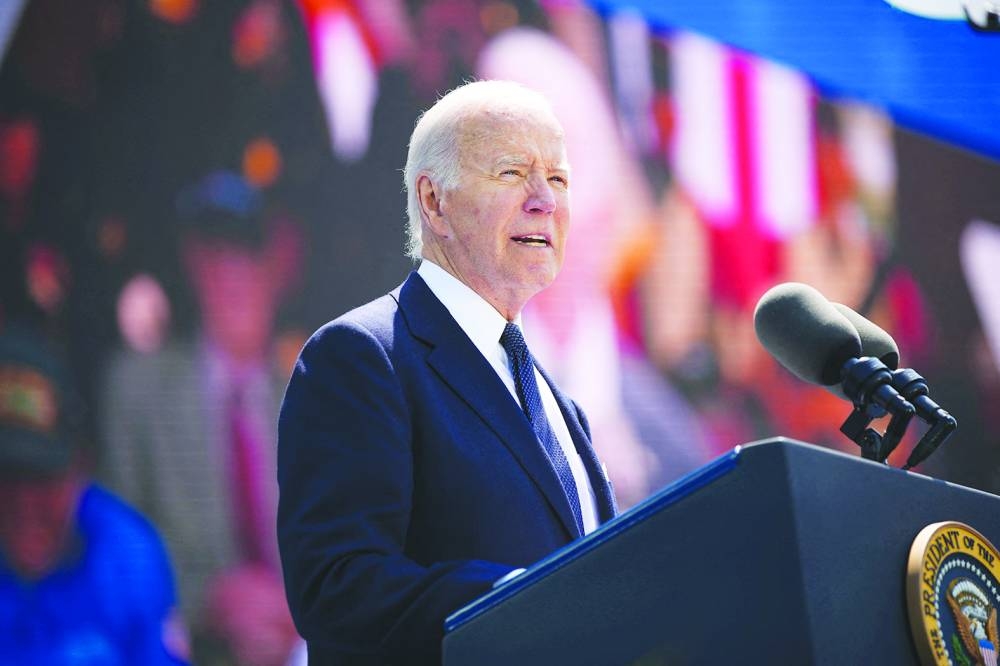

The worst strategy for democrats around the world, and for the Democrats in the US, would be to imitate their opponents. That is a game they cannot win. Yet that is precisely what many are doing. Consider US President Joe Biden’s new package of China tariffs, which is a more radical reversal of traditional US trade policy than anything Trump himself embraced during his presidency.

While headlines have emphasised the 100% tariff on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs), the real story concerns batteries, steel, aluminium, and semiconductors. Though the public doesn’t buy these goods directly, they are inputs in many US-made products and appliances. Presumably, the Biden administration is hoping that Americans will feel hardly any economic effect, and will only see it getting tough with China.

We know what the tariffs won’t do. They won’t create (or “bring back”) many jobs in the US, because if America were to manufacture EVs or solar panels on a large scale, it would rely almost entirely on automated factories. Nor will the tariffs improve relations with US allies, such as by encouraging “friend-shoring.” Instead, European producers are likely to lose markets for engineering products sold to China, as Chinese domestic industrial production ramps up.

The tariffs also won’t accelerate decarbonisation. On the contrary, by making essential green technologies more expensive (thus delaying their mass uptake), Biden will make the world warmer. Moreover, as a recent European Bank for Reconstruction and Development report shows, it remains the case that the minerals and rare earths (gallium, germanium) needed for the expensive parts of battery technology are mostly sourced from China.

Lastly, the tariffs will not improve China’s human-rights record. They will merely encourage those who already believe that American rhetoric on human rights is pure hypocrisy and can safely be ignored.

But the tariffs will have an impact: they will help Biden lose the election. No matter how high the current administration sets them, Trump will always be able to claim that he would set them even higher. Biden will continue to look like he is merely responding to Trump’s challenge – and in a half-hearted, geriatric way.

Moreover, the tariffs have validated the argument by Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin that the old international order is broken because America plays fast and loose with the rules. And most importantly (in the context of an election), the tariffs will aggravate the problem of increased costs for ordinary Americans. The Trump campaign has already made inflation one of its major issues. At his rallies, Trump claims (mendaciously, to be sure) that he can no longer have bacon on his sandwiches, because it costs too much.

The inflation debate is widely misunderstood. Like all Western governments, the Biden administration can point out that inflation has fallen rapidly and is within range of the old 2% target. But that doesn’t matter to ordinary people. They see that costs have risen dramatically since the Covid-19 pandemic, ending a long period of price stability.

While cumulative inflation might be around 20% since 2020, the perception is even worse, because consumers and the media tend to focus on just a few extra-inflationary items, like Trump’s bacon. Housing and food have become much more expensive. A gallon of milk that cost $3.25 at the beginning of 2020 cost more than $4 by 2022; a dozen eggs went from $1.45 at the beginning of the pandemic to $4.82 in January 2023, before falling to $2.86. At the same time, voters don’t think about clothing and other items whose prices have remained relatively stable – or even declined, as in the case of EVs. But they probably will notice an increase in prices for a wide range of consumer products as a result of the new tariffs.

Here, the 1970s offer some lessons. Back then, the US tried to exclude Japanese cars and other manufactured goods that were cheaper and more efficient. The result was only momentarily beneficial for US producers. In the medium term, they lost markets and credibility; and in the long run, they had to adapt belatedly to new techniques. Protectionism cost US carmakers valuable time in making changes, and ultimately destroyed rather than created jobs. It also alienated consumers who were worried about inflation, ultimately contributing to President Jimmy Carter’s defeat in the 1980 election.

In 2023, the Biden administration took great pains to explain that it wasn’t decoupling from China, only “de-risking.” But now, in a fit of panic, it has adopted an aggressive policy of conscious decoupling.

A government will not suddenly inspire voters because it decided to “decouple,” nor will it make any meaningful progress combating climate change by shifting the costs to others. In 1944, US secretary of the treasury Henry Morgenthau observed that “prosperity, like peace, is indivisible. We cannot afford to have it scattered here or there among the fortunate or to enjoy it at the expense of others.”

That message was correct then, and it is correct now. Political leaders inspire confidence when they can show that their policies are benefiting ordinary people, lowering prices, and making better products available. That is what effective government would look like, and many democracies currently are not delivering the goods. — Project Syndicate

- Harold James, Professor of History and International Affairs at Princeton University, is the author, most recently, of Seven Crashes: The Economic Crises That Shaped Globalization.