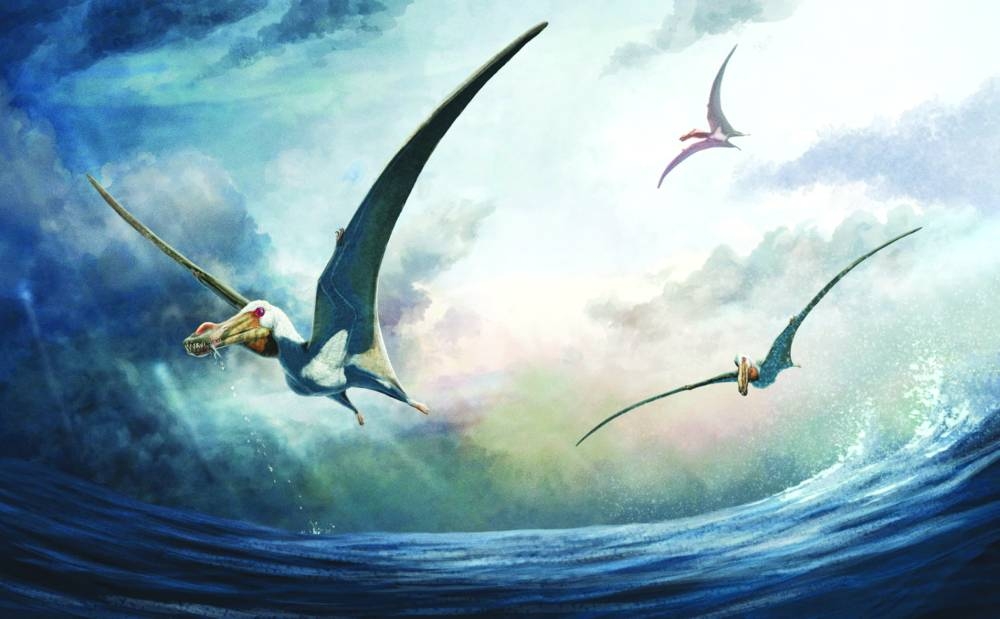

Long ago in the skies above the shallow Eromanga Sea, which once covered what is now arid inland Australia, soared a formidable pterosaur - flying reptile - boasting a bony crest at the tip of its upper and lower jaws and a mouthful of spike-shaped teeth ideal for snaring fish and other marine prey.

Scientists have announced the discovery in the Australian state of Queensland of fossils of this creature, which lived alongside the dinosaurs and various marine reptiles during the Cretaceous Period.

Called Haliskia peterseni, its remains are the most complete of any pterosaur ever unearthed in Australia.

It had a wingspan of 15 feet and lived about 100mn years ago, making Haliskia a bit larger and older - by about 5mn years - than the closely related Australian pterosaur Ferrodraco, whose discovery was announced in 2019.

Haliskia means “sea phantom”, and this creature may have been a frightful sight airborne above the waves.

“The Eromanga Sea was a massive inland sea covering large parts of Australia when this pterosaur was alive, but both have vanished. The ghost of both of these is evident from the fossils found in the area,” said Adele Pentland, a doctoral student in palaeontology at Curtin University in Australia and lead author of the study published this week in the journal Scientific Reports.

The fragile skeletons of pterosaurs do not lend themselves well to fossilisation. For Haliskia, 22% of the skeleton was unearthed, with complete lower jaws, the tip of the upper jaw, throat bones, 43 teeth, vertebrae, ribs, bones from both wings and part of one leg.

“We inferred the presence of a muscular tongue based on the relative length of the throat bones, compared to the length of the lower jaw,” Pentland said.

“In many other pterosaurs, the throat bones are 30% or 60% the length of the lower jaw, whereas in Haliskia the throat bones are 70% the length of the lower jaw. This meant that whilst hunting fish and squid-like cephalopods, Haliskia might have had an advantage and been able to trap live prey in its jaws,” Pentland added.

Pentland said she was “astounded” that the Haliskia specimen preserved throat bones. “These are as thin as a piece of spaghetti, and one is complete from end to end,” Pentland said.

A life reconstruction of the newly identified Cretaceous Period pterosaur Haliskia peterseni, which lived in Australia about 100mn years ago .