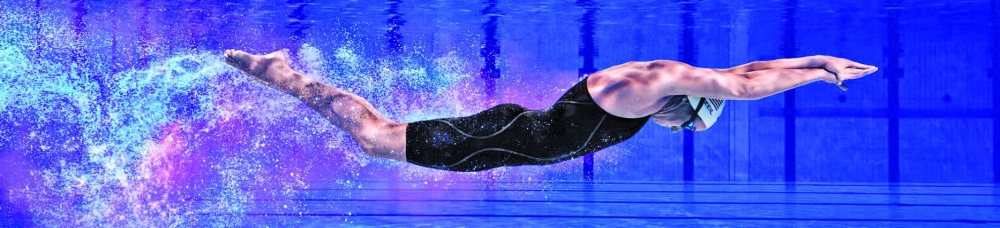

Swimmers battling for gold at this month’s Paris Olympics are banking on the latest cutting-edge swimsuits to be their secret weapon in the pool.

Competitors believe innovation can be the difference in a sport where medals are sometimes decided by a mere fingertip, although the evidence is not so sure.

Driven by technology that takes inspiration from space travel, Speedo has produced a new version of its Fastskin LZR Racer suit billed as its most water-repellent ever.

Claiming to provide a sense of “weightlessness”, it will be worn by top swimmers including Emma McKeon from Australia, the American Caeleb Dressel and Britain’s Adam Peaty as they strive to shave every hundredth of a second off their times.

“It’s my own little Speedo rocket suit,” said freestyle and butterfly ace Dressel, who won five gold medals at the Tokyo Olympics in an earlier version of the suit.

“I’m feeling confident that the (new) suit is going to help me,” he added.

McKeon, who won seven medals including four gold at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, called her new attire “faster than ever” with water “just gliding off”.

The suits use a coating technology originally used to protect satellites.

They are the latest development in a battle for supremacy spanning decades with other brands such as Arena, Mizuno and Jaked to push the boundaries ever further.

“The biggest factor in swimming, because it’s in water, is drag, which is far and away the main detractor for speed,” Kevin Netto, a specialist in exercise science at the Curtin School of Allied Health in Perth, told AFP. “So anything that will change drag forces, it’s worth its weight in gold.”

Over the years swimsuits have progressed through flannel, rayon, cotton, silk, latex, nylon and lycra.

They are now required by World Aquatics to be made from permeable materials since Speedo’s controversial full bodysuit used at the 2008 Beijing Olympics was branded “technological doping”.

Seamless and part-polyurethane, it was designed with the help of Nasa to aid buoyancy and support muscles, significantly reducing drag and making it easier to swim faster for longer.

It contributed to a bumper crop of world records at the Games in China.

Even more advanced models followed, including part-polyurethane suits by Arena and the all-polyurethane Jaked 01, which saw another burst of records at the 2009 world championships.

World Aquatics, then known as FINA, banned polymer-based suits from 2010 after mounting criticism that they offered unacceptable performance-enhancing properties.

Full body suits are also outlawed. They can now only be worn from kneecap to navel for men and knee to shoulder for women.

Minimising surface drag from the water remains a key task of the current suits, compressing the body to aid streamlining.

“If they provide some sort of compression, you don’t have any wobbling mass in the water,” Netto said. “It basically keeps the human shape very, very streamlined, you don’t produce more oscillation or wave drag.”

But for all that, the suits’ influence on performance remains inconclusive despite reams of research, with advances in diet and training increasingly contributing to swimmers going faster.

In 2019, the European University of Madrid examined 43 studies into the subject and concluded that there was no clear consensus.