Growing up in Greece, one of my most joyous childhood memories was the announcement that the school (and work) week would shrink from six days to five. Since I also recall my compatriots being equally excited about the change, I was surprised to hear that under a new law, employers in several sectors may once again implement six-day schedules.

This change is surprising for many reasons. First and foremost, it seems to buck a general trend toward fostering work-life balance and allowing for more flexible work arrangements. Several governments in advanced economies (Belgium, Singapore, and the United Kingdom) have announced shorter work weeks, and others (Germany, Japan, Ireland, South Africa, and Spain) are contemplating similar changes.

Second, Greeks are known for appreciating work-life balance, and they already work more hours than other Europeans. The average Greek worker spends 39.8 hours per week on the job, compared to an average of only 36.1 hours across the European Union.

Third, although the current Greek government is pro-business and pro-growth, it has shown an appreciation for the rights and advancement of women, a group that is likely to be adversely affected by a longer, less flexible work schedule. This same government has also demonstrated a commitment to evidence-based policymaking, and the evidence to date suggests that shorter work weeks and a more balanced lifestyle contribute to higher employee satisfaction, better health, and ultimately greater productivity.

So, what explains this unexpected policy change? The government itself describes the move as an “exceptional measure,” which we all know to be a euphemism for “policy of last resort.” Like many high-income countries, Greece is facing an acute labour shortage. While its situation is particularly dire, owing to a substantial labour drain following the 2010 financial crisis (about 500,000 Greeks – 5% of the current population – are estimated to have left), it is not alone.

The root of the problem lies in low fertility and an ageing population – demographic conditions that the Greek government rightly characterises as a “ticking time bomb.” Coupled with well-founded demands for a higher quality of life and better work-life balance as people become wealthier, fewer working-age people constrains labour supply.

How should advanced economies address this problem? Four possibilities come to mind. The first is to embrace automation, on the assumption that machines, robots, and artificial intelligence could eventually take the place of missing workers. But not every job can be performed by a machine or a large language model. We still need humans to fill many of the least desirable low-skilled positions in construction or the food and hospitality industries.

The second option is to increase worker compensation. Basic economics teaches us that when demand exceeds supply, prices (in this case, wages) go up. But higher wages ultimately lead to higher prices for consumers, which tend to be unpopular, especially at a time when inflation is a primary concern. And in a small open economy like Greece, higher wages and prices would have detrimental effects on international competitiveness.

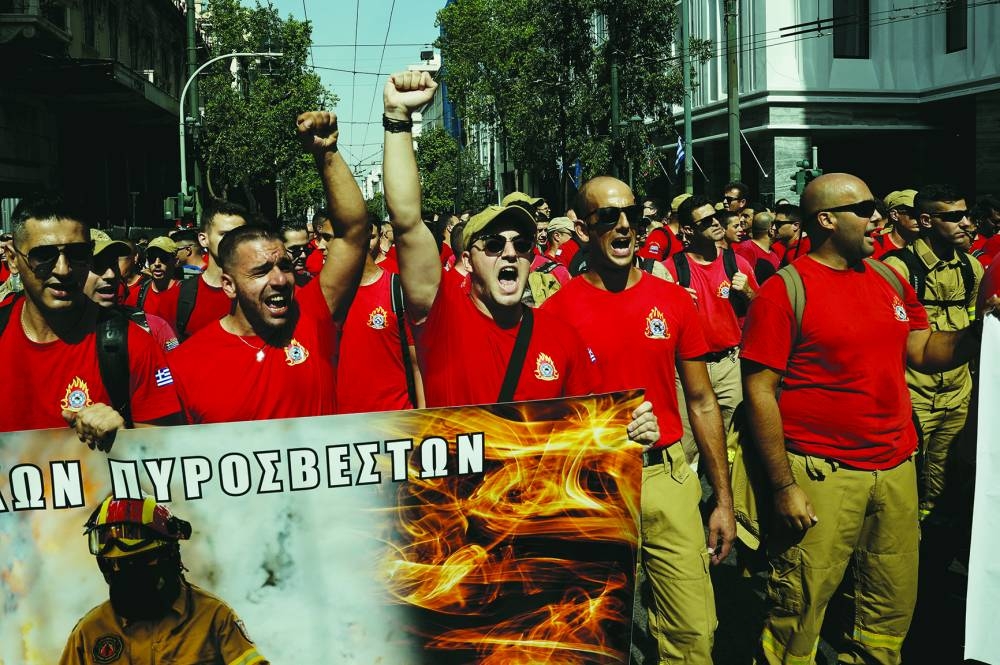

The third option is to ask workers in advanced economies to work more, as Greece has now done. While this move appears to be bucking the general trend toward fewer work hours per week, it actually is not so different from increasing the retirement age, as several other countries (Denmark, France, Germany) have found it necessary to do. In both cases, the policy changes have been highly unpopular among workers; and in both cases, people sent a clear message that they would rather forego the higher income (in Greece’s case, the sixth workday comes with a 40% wage premium) than work more than they are used to.

This leaves us with the fourth option, which is to increase the labour supply by harnessing controlled, legalized immigration. In regions plagued by refugee crises and illegal immigration (such as most of Europe and the US), properly designed immigration policies have the potential to kill two birds with one stone. Yet such policies currently seem out of the question. In the face of geopolitical fragmentation and national-security concerns, countries are increasingly closing their borders and turning inward.

One is reminded yet again that in a globally interconnected world, the distinction between foreign and domestic is tenuous. Problems originating in other parts of the world have important implications for domestic issues, and in this case for labour markets.

There is of course a fifth option, which is for people in richer countries to scale back their consumption and growth and rely on the fruits of the labour they are willing to supply. Doing so would provide the work-life balance they seek, as well as ensuring a sustainable future. But as of now, few are willing to accept this tradeoff.

Most people want to have their cake and eat it. But that isn’t possible. To maintain their current quality of life, citizens of high-income countries must either open their borders to new immigrants or work more. Given the current global tensions, the pendulum seems to be swinging in the direction of more work, whether it comes through a higher retirement age or a longer work week. Greece may be more of a trendsetter than a trend breaker. – Project Syndicate

- Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg, a former World Bank Group chief economist and editor-in-chief of the American Economic Review, is Professor of Economics at Yale University.