When Afghan cyclists Yulduz and Fariba Hashimi used to train on the dusty roads at home, men would hurl stones and insults, but their years of hard graft have now paid off, winning the sisters a place at the Paris Olympics. The Hashimi siblings are the first cyclists - male or female - to represent Afghanistan at the Games. But taking part is about far more than chasing medals.

“I want to represent the 20mn Afghan women who lack even the most basic rights,” Yulduz, 24, said by video call from Switzerland, where the sisters now live. “I hope to be their voice and show the world the conditions Afghan women face and how, despite these challenges, they can achieve great feats.”

The Paris Games are the first summer Olympics since the Taliban seized the country in August 2021. The administration has since imposed harsh restrictions on girls and women, banning them from education, jobs and sport. With all eyes on Paris, the sisters want to “present a new image of Afghanistan and Afghan women to the world”.

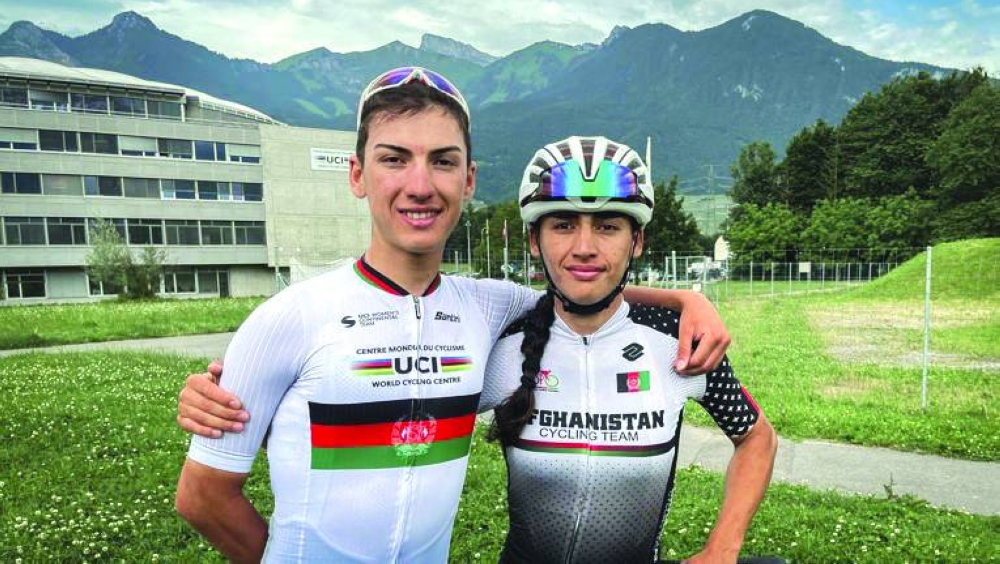

The six-person team - three women, three men - was announced in June: the gender-equal squad a clear message to Kabul. They will compete in the red, green and black of Afghanistan’s tri-colour flag, which the Taliban have replaced.

The team was drawn up following talks between the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and senior figures from Afghanistan’s National Olympic Committee living in exile. Yulduz will compete in the women’s time trial on Saturday.

On Aug 4, both sisters will line up with the world’s top cyclists near the Eiffel Tower for the women’s road race - a gruelling 158-km (98-mile) route with multiple climbs. The Taliban government does not recognise the female athletes - the Hashimi sisters and sprinter Kimia Yousofi. No members of the Taliban have been invited to the Games.

Yulduz and Fariba, 21, grew up in Faryab, a deeply conservative, northern province bordering Turkmenistan. When the sisters decided to enter a local cycling competition as teenagers they did not even know how to ride a bike and had to borrow one to learn. “No one ever thought that women would ride bicycles in Faryab,” said Fariba. “We thought it would be a small contest, but it caused quite a stir.”

Afraid their parents would disapprove, they kept the race secret, disguising themselves in loose clothes and sunglasses. They came first and second - and were immediately hooked. The sport gave them a feeling of liberation missing in their day-to-day lives. “When I rode a bicycle for the first time, I felt a sense of freedom,” Yulduz said.

Far from disapproving, their father, a doctor, and housewife mother were both supportive. Others were not - so the sisters would often train in the evening, with fewer people around to object. “Some people said cycling wasn’t suitable for girls and accused us of encouraging women and girls into immoral activities,” Yulduz added. “We were afraid something bad might happen to us, and someone might harm us.”

And indeed someone did - a rickshaw driver rammed Yulduz while she was training, breaking her wrist. Another time, bystanders - incensed by the sight of women and men training together - pelted them with stones and abuse.

The sisters were invited to join Afghanistan’s national women’s cycling team in 2020. But fears for the safety of women cyclists grew as the Taliban swept through the country in 2021. By that time, Yulduz was studying literature at university and Fariba was hoping to study medicine.

The sisters fled after the fall of Kabul with the help of Italian former world champion cyclist Alessandra Cappellotto. They settled in northern Italy, where they resumed their training on the twisty mountain roads of the Little Dolomites. Cappellotto arranged everything from language lessons to contracts with an Italian cycling team.

In 2022, Fariba was crowned Afghan women’s cycling champion after inching ahead of her sister at the Women’s Road Championships of Afghanistan - a contest held in Switzerland for 50 Afghan cyclists living in exile. The race was hosted by the UCI, the world governing body for cycling. The Hashimis have since joined the UCI World Cycling Centre’s women’s team in Switzerland.

The sisters doubt the Taliban-controlled media will broadcast their Olympic debut, but hope that family and friends will catch highlights on social media. They said they felt energised by the many messages of support they had received from their compatriots, including women cyclists still in the country.

“They told me to go and bring victory under Afghanistan’s flag,” Fariba said. “My sister and I might be among the first girls to go to the Olympics, but I hope we’ll open a path for other Afghan girls.”

Cappellotto, who has become a mother figure to the sisters, will be in Paris cheering them on. “They are very strong,” she said. “They’ve made amazing progress. They’ve learnt in two years what European girls learn in 10.” Cappellotto said the sisters were such phenomenal climbers that they could one day win the mountain stage of the women’s Tour de France.