Noor Miah was a student when riots broke out in northern England in the summer of 2001, with angry young British South Asians clashing with police after a series of racist attacks and incidents.

The northern town of Burnley was engulfed in the riots which began an hour away in Oldham, as the far-right stoked racial tensions and minority communities accused the police of failing to protect them.

More than two decades later, Miah recalled that dark period as he tried to calm Muslim youths in Burnley after several Muslim gravestones in the local cemetery were defaced and far-right riots targeted mosques in nearby cities. “2001 was a difficult time for Burnley. We have moved onwards since then, picked ourselves up. The next generation has a lot of hope,” Miah, now a secretary for a local mosque, told AFP.

On Monday, Miah received a message from a friend who found a family member’s grave covered in paint.

“When I rushed to the cemetery there were already a couple of families, who were really concerned, really emotional,” Miah said, with around seven gravestones vandalised with grey paint. The act is being treated as a hate crime by local police.

“Whoever’s done this is trying to provoke the Muslim community to get emotionally hyped up and give a reaction. But we have been trying to keep everyone calm,” Miah said.

“It’s a very low thing to do. No one deserves this...things like this shouldn’t happen in this day and age.”

The attack has added to the fear among Burnley’s Muslims, after anti-immigrant, Islamophobic riots occurred in other northern towns and cities in the last week. The violence followed a mass stabbing on July 29 in Southport, near Liverpool, in which three children were killed, which was falsely blamed on social media on a Muslim migrant.

Miah worries about his wife going to the town centre wearing a hijab and has told his father to pray at home instead of at the mosque “to limit how much time he spends outside”.

“I helped build that mosque, I physically moved bricks there. I was part of that mosque, but I have to think about my family’s safety,” he said. But Miah still hoped there would be no violence. “We haven’t had riots yet here. Hopefully the riots won’t come to Burnley.”

In Sheffield, violence hit close to home for Ameena Blake. Just a few miles away in Rotherham, hundreds of far-right rioters attacked police and set alight a hotel housing asylum seekers on Sunday.

While Blake, a community leader on the board of two local mosques, said Sheffield is a place of “sanctuary”, Rotherham “is literally on our doorstep”. Since the weekend riot, there has been “a feeling of massive fear”, especially among Muslim women, Blake said.

“I’ve had Muslim sisters who wear hijab contacting me saying, ‘I’m worried about going out with hijab.’” Like Miah’s family in Burnley, here too “people have been staying in their homes”.

“I know of sisters who usually are very independent...who now won’t go out without a male member of the family dropping them off and picking them up because they don’t want to be out in the car alone.”

The government has announced extra security for the places of worship in the wake of the violence, which reportedly left mosque-goers in Southport trapped inside the building during clashes.

While the last two major bouts of rioting to rock England in 2001 and 2011 involved an outpouring of mistrust and anger against the police by minorities, this time police forces have worked alongside Muslim community leaders to urge calm.

“Historically, there has been a lot of mistrust in the police between BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic) communities, Muslim communities,” said Blake, who is also a chaplain for the South Yorkshire police in Sheffield.

“Communities have almost parked to one side the mistrust and the historical issues to join together (with the police) to tackle this very, very real problem.”Support from the police and government has been “really amazing, and to be honest, quite unexpected”, Blake added. As Friday prayers beckoned, Muslims in Sheffield were feeling “quite nervous and vulnerable”. But people will go to mosques, Blake said. “There is fear, but there’s also very much a feeling of we need to carry on as normal.”

Police officers stand guard at the East London Mosque in Tower Hamlets.

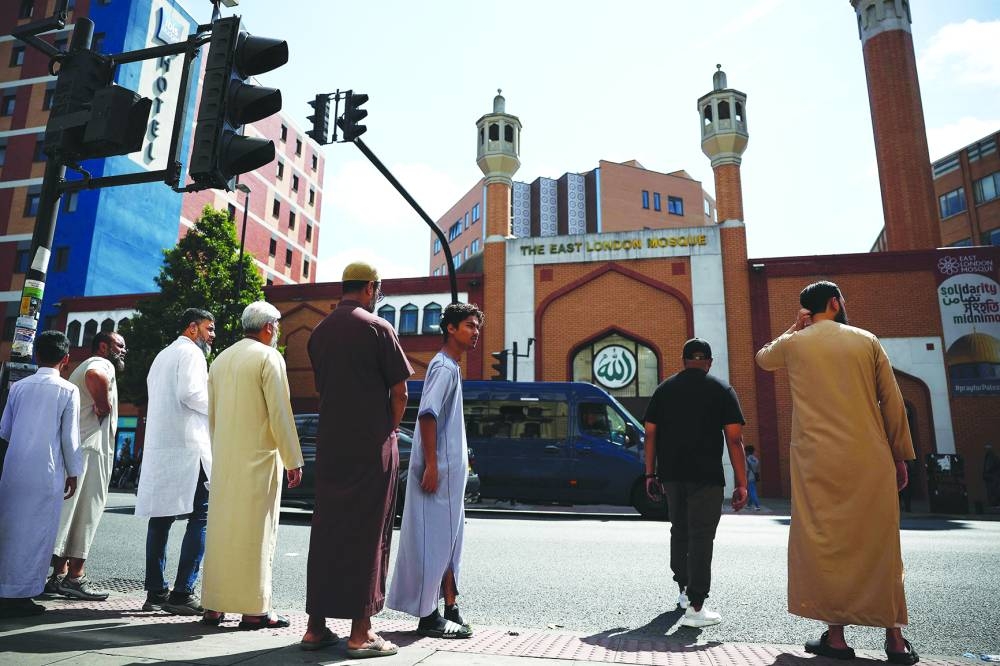

Worshippers outside the East London Mosque in Tower Hamlets, London.

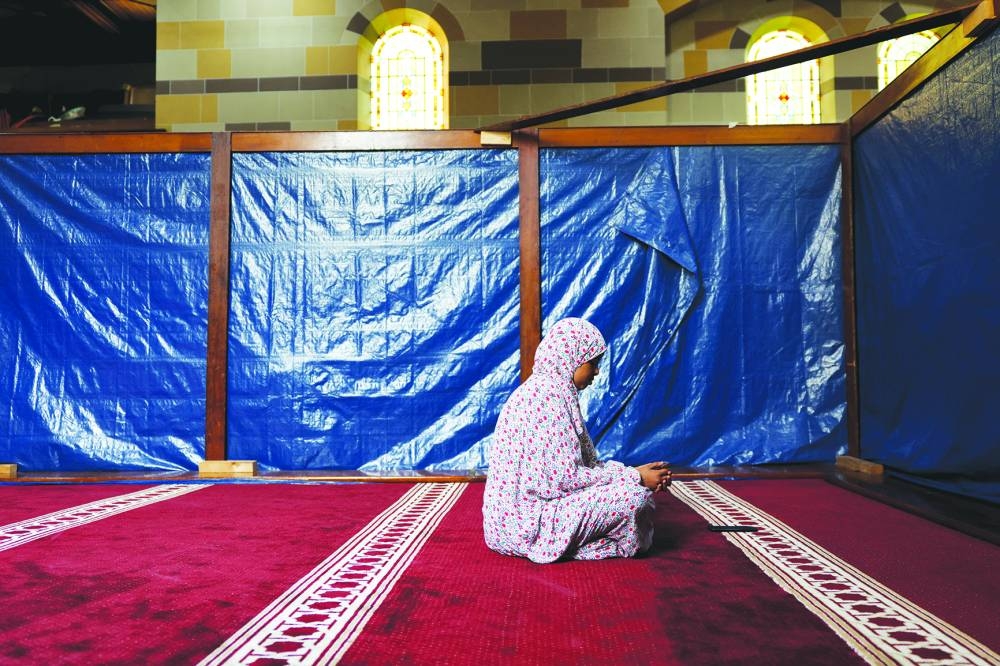

A Muslim worshipper attends Friday prayers at Iqraa Dunmurry Mosque in Belfast, Northern Ireland.