When he takes office in January, President-elect Donald Trump will inherit a raft of national security challenges, including major wars in Ukraine and the Middle East.

Less discussed are the growing nuclear threats facing the United States, including from Russia, China and Iran.

Here are the five most pressing nuclear arms challenges confronting Trump:

Russia

Trump will have to manage the gravest tensions with Moscow in more than 60 years, in part fuelled by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s threats to use nuclear weapons in his war against Ukraine and his development of exotic new weapons systems.

Overseer of the world’s biggest nuclear arsenal, Putin has been modernising his nuclear forces and has rejected talks with Washington on replacing New START, the last US-Russia arms limitation pact, when it expires on February 5, 2026.

US officials say Putin remains within the limits set by the treaty despite his 2023 “suspension” of the pact that holds Russia and the United States to deploying 1,550 strategic nuclear warheads on 700 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarines and bombers.

President Joe Biden and Putin agreed to an extension in 2021 but, as written, the pact can’t be extended further. Trump opposed an extension in his first term, calling instead for a new treaty that included China, which spurned the proposal.

Putin cited Washington’s support for Ukraine in rejecting Biden’s invitations for unconditional talks on replacing New START. But both sides say they will adhere to the treaty’s limits as long as the other does.

China

China - which long had a smaller nuclear arsenal - is building up its strategic nuclear forces.

The Pentagon in 2020 estimated that Beijing’s operational nuclear warhead stockpile numbered in the low 200s and was expected to double by 2030.

That estimate was revised two years later, with the Pentagon saying China likely would have 1,500 nuclear warheads by 2035 if the pace of its buildup continued.

Beijing and Washington held their first nuclear risk reduction talks in nearly five years in November 2023.

But China, which has a “no-first-use” doctrine, in July formally halted further bilateral arms control discussions in protest against U.S. weapons sales to Taiwan, the democratically ruled island claimed by Beijing.

United States

Trump will have to craft a policy on deterring nuclear threats from Russia and China even as he confronts the expiration of New START.

The Biden administration says the United States might have to deploy more strategic nuclear weapons in the future and Trump could do just that. In his first term, Trump’s nuclear weapons policy called for new capabilities, reversing decades of US arms reduction efforts, and he opposed extending New START.

But he will confront the soaring costs of America’s own modernisation of each leg of the US nuclear “triad” - ICBMs, bombers and submarines - major parts of which are behind schedule and far over budget.

The costs of the effort, which has grown to include new warhead designs, missiles, a bomber and a submarine, are projected by the Arms Control Association advocacy group to exceed $1.5 trillion over the next 30 years.

Experts say that amount is certain to rise, threatening to divert funds needed for conventional US military forces or for non-defence programmes. “At a certain point, we will hit a constrained budgetary environment,” warned a congressional aide, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Iran

Iran may decide to build nuclear weapons following tit-for-tat strikes with arch-foe Israel and Biden’s failure to revive major power talks with Iran on restoring curbs on its nuclear programme.

Washington and its European allies will lose leverage over Tehran when a UN Security Council resolution allowing a “snapback” of international sanctions on Iran expires next October.

The sanctions were lifted in return for Iran accepting strict limits on its programme under a 2015 deal designed to prevent it from developing nuclear weapons.

Trump withdrew the United States from the pact in 2018, leading Iran to breach its limits. The time Iran would need to make enough highly enriched uranium for a warhead has now been cut from a year to just weeks or days, US officials say, although Tehran would need some more time to build an actual bomb.

Iran denies US and UN nuclear watchdog assessments that it shuttered an effort to build a nuclear warhead in 2003 and has offered to reopen nuclear talks.

But the Israeli strikes could prompt Tehran to resuscitate that effort. Following the strikes, a top Iranian official said Tehran possibly could review its self-imposed ban nuclear weapons development.

North Korea

Tensions with North Korea have grown over Pyongyang’s co-operation in Moscow’s war against Ukraine and an October 31 test of a new ICBM that underscored the country’s ability to hit most of the United States with nuclear weapons. A recent US Defence Intelligence Agency report said Pyongyang continues expanding stockpiles of materials for its nuclear weapons program.

It also noted that North Korean leader Kim Jong-un set out a defence plan in 2021 calling for producing tactical warheads, “lighter nuclear weapons” and “ultra-large nuclear warheads”. The Federation of American Scientists estimates that North Korea, which has conducted six underground nuclear test blasts since 2006 and more than 100 missile launches since 2022, has enough fissile material for up to 90 warheads, but “potentially” has assembled just 50. Biden’s administration has been unsuccessful in persuading Kim to revive denuclearisation talks that collapsed after Trump failed in 2019 in the last of three meetings to convince the North Korean leader to abandon his nuclear weapons.

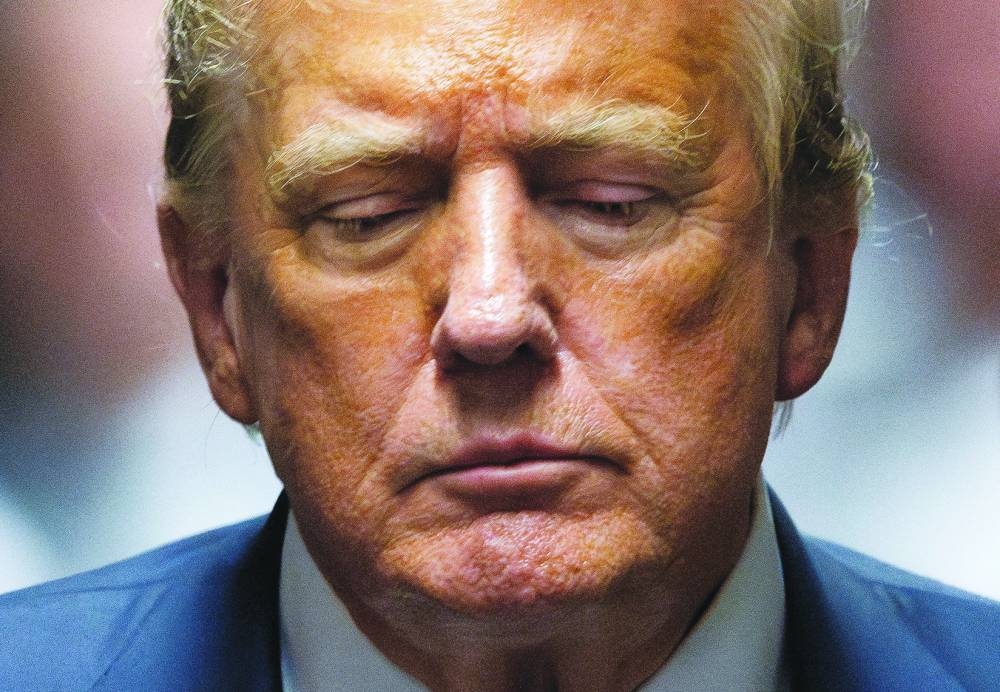

President-elect Donald Trump will have to manage the gravest tensions with Moscow in more than 60 years, in part fuelled by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s threats to use nuclear weapons in his war against Ukraine and his development of exotic new weapons systems. (Reuters)