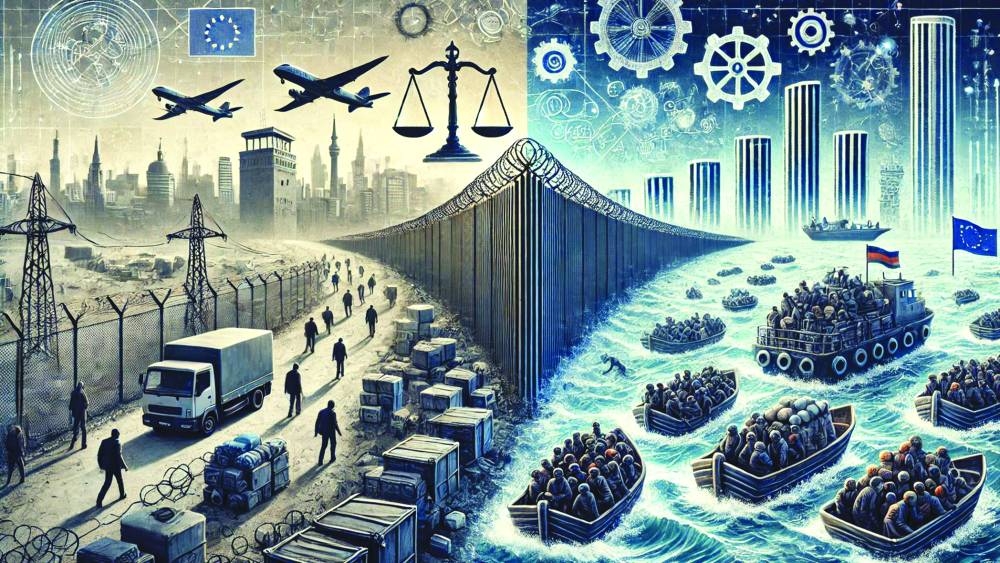

Growing support for parties across Europe looks set to shape migration policy in 2025 after a bumper election year in which immigration became a major political battleground.

With the European Union gearing up to implement its revamped asylum pact by 2026, some countries are calling for the rules fast-tracking asylum processes and returns to be sharpened or implemented sooner.

Rights groups say this would risk rolling back people’s rights to seek asylum and put them at risk of arbitrary detention and increased pushbacks by authorities operating on Europe’s external borders.

While immigration remains a highly sensitive topic in most of the bloc’s 27 member states, the number of irregular migrants arriving in Europe has dropped from around 1mn in 2015 to around 220,000 in 2024, according to data from the EU’s border agency Frontex.

So what’s in store for migration policy in Europe in 2025?

‘Smashing’ smuggling

Britain’s Prime Minister Keir Starmer has made cracking down on illegal migration by combatting gangs of people smugglers a cornerstone of his migration policy, reaching deals with his Italian and German counterparts to “smash the gangs”, as well as signing a security pact with Iraq to target smugglers and strengthen border cooperation.

In 2025, EU lawmakers are set to vote on the new Facilitation Directive, which aims to tackle migrant smuggling in the bloc. However, humanitarian groups say the current draft fails to clearly exempt those who seek to help migrants, by providing food and shelter for example, from criminal sanctions.

Rights groups add that the focus on smugglers fails to tackle the root cause of migration and could make Channel crossings from France more risky, with 2024 already being the deadliest year on record with at least 69 deaths, according to the Refugee Council.

Rights groups say the crackdown on smuggling has reduced the supply of boats as well as opportunities to launch, leading smugglers to load more migrants onto flimsy vessels, increasing the risk of people being crushed or drowning.

They want European governments to expand safe and legal pathways to international protection.

Fast-track asylums and returns

European governments are also looking at how to fast-track asylum procedures and increase deportation. Under the new asylum pact, people arriving at the bloc’s borders face a rapid screening, and, if rejected, a swift deportation process. Rights groups fear the new expedited border procedure will be used to reject asylum applications without properly assessing individual cases.

Another proposal is to expand the number of ‘safe list countries’ — or countries where people are deemed less vulnerable to state persecution, violence, and armed conflict — to speed up asylum applications.

Under the proposal, people from the ‘safe list countries’, which have a smaller chance of having their asylum applications accepted, can be deported more swiftly if their claims are rejected.

In a major policy shift, the EU is also considering so-called “return hubs” outside the bloc to increase and fast-track deportations of rejected asylum seekers — a plan that has echoes of the United Kingdom’s scrapped plan to fly asylum seekers from Britain to Rwanda.

EU leaders called on the bloc’s Commission to draft a law to speed up deportations last October. Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson recently said the EU could submit a proposal on the creation of so-called “return hubs” as soon as March.

EU countries have also called on the Commission to make the rules governing deporting people that do not have the right to stay in a country more strict. That includes people whose requests for asylum have been rejected or those who lose the right to international protection due changing circumstances.

A new proposal to sharpen the EU Returns Directive is expected in 2025.

Outsourcing asylum

There is growing pressure from EU governments to process asylum applications outside the bloc in countries along the main migration routes.

Last year, 14 countries — including Germany, France, and Italy — issued a joint call to send migrants arriving in the EU to partner countries.

The first deal allowing a non-EU country to process migrants on another country’s behalf was agreed between Italy and Albania last year. But it has been plagued with legal challenges, and only a few of the up to 36,000 non-vulnerable migrants per year Italy said it could transfer to Albania have made it to reception centres.

More than 100 NGOs issued a joint statement criticising the scheme, saying it risks leading to prolonged automatic detention and curbing people’s access to fair asylum procedures. They called on the EU to uphold the right to asylum.

Walls and automated borders

In order to deal with an increase in migrant arrivals and security concerns, some EU countries have extended temporary border checks within the bloc’s area of free movement, the Schengen zone, into 2025. These include Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, and Sweden.

Right-wing lawmakers have called for more funding for physical barriers along external borders in the next EU budget, due to be discussed in the second half of the year.

Europe is increasingly turning to artificial intelligence systems to strengthen border controls, an effort boosted by the bloc’s approval of the AI Act in 2024. The new rules ban high-risk AI tools from the EU from February 2025 but have exemptions for the use of AI in law enforcement and in border zones.

Rights groups fear that AI-powered drones, cameras and other algorithmic profiling technologies are being deployed to detect and repel migrants and refugees, and create a double standard - with one set of rules for EU citizens, and another for migrants and asylum seekers.

- Thomson Reuters Foundation

Opinion

Europe: what will migration policy look like in 2025?

*EU leaders push for tougher migration rules

*Calls for outsourcing asylum procedures grow

*Rights groups say hard line policies endanger lives