From Sarajevo to Skopje, reliance on coal power could expose the Western Balkans to a major economic hit when European Union green tariffs come into force next year.

Coal-fuelled electricity is one of the Western Balkans’ most carbon-heavy exports and will be covered by the EU’s new carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), which will put a levy on imports with a large carbon footprint.

The region’s economic and geographic ties with the EU are “so enormous” that they will find it difficult to escape the tariffs, explained Janez Kopac, former director of the Energy Community Secretariat, which brings together the EU and its neighbours to create an integrated pan-European energy market.

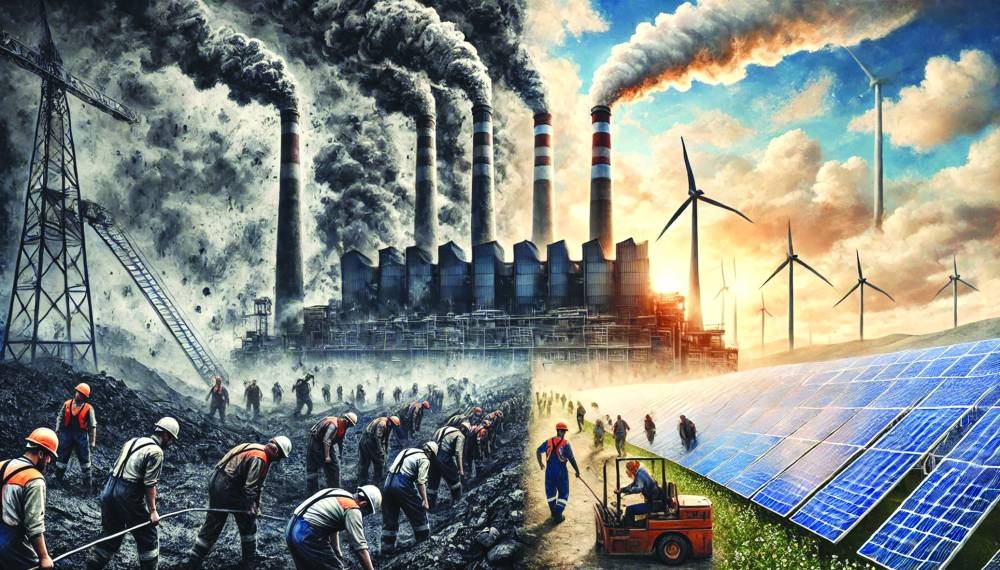

In the Western Balkans, coal accounts for between 60% and 95% of power generation, depending on the country, and 60% of the region’s electricity exports.

Located in southeastern Europe, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia share borders with six EU countries, making the bloc their main trading partner.

Some energy analysts see the impending eco-tariff as an incentive for the region to invest in the clean energy transition as countries progress towards EU membership.

But if they do not, the financial fallout could be significant.

“They will adapt sooner or later, but it will be bumpy for them,” said Kopac.

The new eco-tariff will hit countries differently depending on the carbon footprint of their electricity exports. CBAM fees for EU importers would effectively make electricity exports from the Western Balkans more expensive.

Albania uses mostly hydropower, limiting its exposure, but Bosnia and Herzegovina stands to lose more than €220mn ($231.99mn) in annual revenue from the sale of power to the EU, according to calculations from CEE Bankwatch, a network of central and eastern European environmental nongovernmental organisations.

Western Balkans nations’ efforts to decarbonise have largely stalled, according to the Energy Community’s CBAM readiness tracker.

Analysts say a lack of investment in renewable energy and continued government subsidies for ageing coal plants are hampering the green transition, leading governments to seek delays or exemptions from CBAM.

Any exemption would come with conditions, including massive investment in clean energy or the introduction of country-specific carbon pricing, making it hard for countries to bring in reforms before the CBAM goes into effect.

“Nobody is really ready,” Pippa Gallop, Southeast Europe energy adviser at CEE Bankwatch, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

But she said there is growing awareness that countries are going to have to decarbonise if they want to “escape the worst impacts.”

Switching from coal to clean energy comes with hefty social and economic costs.

German clean energy think tank Agora Energiewende prices the energy transformation in the Western Balkans at around €40bn, a figure which does not include the retraining or severance packages of approximately 30,000 coal workers.

Rather than incentivising an exit from coal, the eco-tariffs could hobble the Balkans’ green transition by taking away cash needed to fund the transition, said Christian Egenhofer, senior researcher on energy policy at the Brussels-based CEPS think tank.

“These people need money, not such incentives,” he said.

EU countries have a specific Just Transition Fund, worth €17.5bn , to shield workers and regions from the economic fallout of clean energy shifts like plant closures. The Western Balkans has no such dedicated funding.

To support EU integration, the bloc has made available up to €9bn to fund the green and digital transition and up to €20bn of investments via the Western Balkan Guarantee Facility to cover all reforms needed to join the EU – not just modernisation of the energy sector.

Gallop from CEE Bankwatch said the funds were “not enough in terms of volume” to match the investment needed for a just transition. No matter how much money the EU provides, some impetus for change would have to come from the Western Balkan states themselves, said Kopac.

“Perhaps this is not a question for the European Union anymore,” he said. – Thomson Reuters Foundation