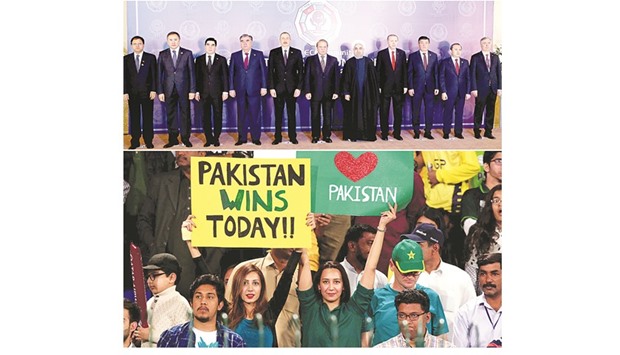

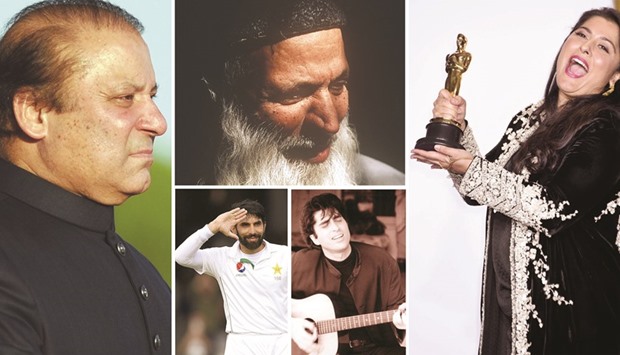

The other week, China sent out the strongest message yet of its ambition to carve out what has the makings of a ‘new world order’ — something that had until now been considered the sole preserve of the United States, especially since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. With the unfancied Donald Trump winning the election on the pivot of “Making America Great Again” — designed around an inward policy — and one that is cast in a protectionist mould, a confident China finds itself free to pursue an economic zeitgeist that has the potential to turn it into the world’s leading power. In this larger scheme of things, it finds heavyweight Russia on its side quite simply because their strategic interests converge. The One Belt, One Road — or OBOR, to be more succinct — saw heads of state and government from 29 countries, representatives from more than 40 other countries, and heads of UN and multilateral financial agencies, including IMF and World Bank, turn up in Beijing. An eye for a pie in the trillion dollar infrastructure development project that links the old Silk Road with Europe was palpable. Even the US and Japan sent delegations. The who’s who were keen on getting to know what’s what of the phenomenal juggernaut that, at the moment, binds 68 countries from Asia and Africa to Europe and even South America — accounting for up to 40 trillion of the world’s GDP — in a potential partnership whose gravitas for a windfall is lost on no-one. The OBOR initiative is a manifestation of the shifting sands in global geopolitics, where look-East will hoist Eurasia at the centre of economic and trade activity away from the US-led transatlantic regime. To be certain, Chinese President Xi Jinping has made the OBOR initiative the centrepiece of his infrastructure behemoth, the sheer scale of which, the world has not seen since the end of the Second World War. According to Chinese government estimates, nearly $1tn has been invested in the OBOR with multiple trillion more to come in the next decade. Beijing is also pumping a collective $150bn in development projects in the 68 countries that are part of the project. The only major regional country to abstain from the epoch-making summit in Beijing was India, which has serious reservations about the project owing to its competing interests with China and the OBOR flagship project — China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) — which pitches Pakistan right at the fulcrum of the path leading to South and Central Asia. Both China and Pakistan have offered India to join the profitable engine of economic growth, but so far it remains wary of the geographical bind that has Pakistan sitting pretty with a bilateral engagement (CPEC) estimated at approximately $57bn, and which, is expected to grow exponentially in the coming years. It has seen a surge of nearly $11bn in the last three years alone from an initial projected $46bn! For Islamabad, of course, this is more than a prized venture that promises to turn its fortunes around. Once it materialises, it will have insulated Pakistan from any untoward economic downturn and largely addressed the perennial issue of capital. From initial misgivings at home about unequal distribution thanks to political bickering, CPEC has now assumed a certain unity of purpose four years down the road, which was evident in how Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif invited chief ministers of two provinces where his political rivals rule, and both not only accepted the invitation but were a prominent presence in an official delegation led by Sharif that easily outscored every other country at the summit! The CPEC has elevated a more than five-decade-old strategic partnership based largely on security cooperation — famously dubbed as being “Higher than the Himalayas and Deeper than the Oceans” — into a dynamic economic relationship whose reach and potential entwines them in an unbreakable bond. While China would literally, expand its economic might thousands of miles across the region, Pakistan can hardly complain about being the gateway for two routes — the continental Eurasian Silk Road Economic Belt and a Southeast Asian Maritime Silk Road! Prime Minister Sharif had plenty to smile about as he oversaw the signing of new wide-ranging accords amounting to $500mn, including an airport in Gwadar — the site of a deep water port that opens into the Arabian Sea from the far western Chinese province of Xinjiang; the setting up of a dry port in Havelian in northern Pakistan; and economic and technical co-operation for the East Bay Expressway linking Gwadar to Pakistan’s highway network. Addressing the plenary session of the two-day powerhouse of a show in Beijing, Sharif called for finding a connect in line with the official theme entitled ‘Co-operation for Common Prosperity’. “It is time we transcend our differences, resolve conflicts through dialogue and diplomacy and leave a legacy of peace for future generations,” he emphasised, before driving home the imperative of peace and security through economic progress. “The OBOR signifies that geo-economics must take precedence over geo-politics, and that the centre of gravity should shift from conflict to cooperation,” he said, and rejected the notion of encirclement of any country. President Xi underlined this by allaying concerns that OBOR was designed to manipulate geopolitics for Beijing’s vested interest. “China is willing to share its development experience with all countries. We will not interfere in the internal affairs of other countries. We will not export our social system and development model, and will not impose our views on others,” he concluded. * The writer is Community Editor

Kamran Rehmat

Kamran Rehmat is the Op-ed and Features Editor at Gulf Times. He has edited newspapers and magazines, and writes on a range of subjects from politics and sports to showbiz and culture. Widely read and travelled, he has a rich background in both print and electronic media.

Most Read Stories

3