|

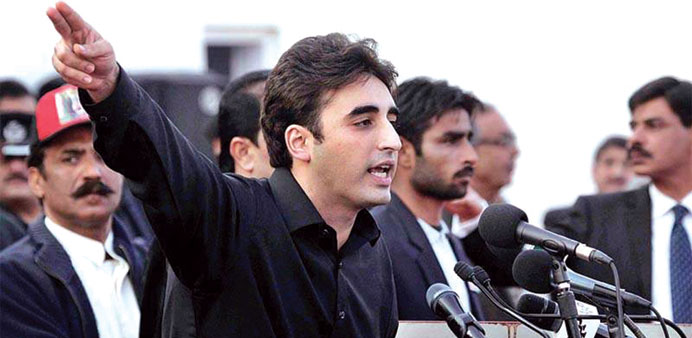

In terms of Pakistani political history, an important milestone took place four days before 2012 yearend. It was the formal introduction of 24-year-old Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari into politics which coincided with the fifth death anniversary of his illustrious mother, the slain former prime minister Benazir Bhutto, and spouse of current president Asif Zardari. |

Love or loathe, the Bhuttos are so intertwined with democracy that it is virtually difficult to separate the two in the Pakistani narrative.

It is almost astonishing that there hasn’t been a Bhutto in parliament for 13 years running. In this while, several rulers have come and gone - dictators and democrats, full time and part time, local and imported, and the young and the old. In fact, the Pakistan People’s Party is on the verge of completing a full term in office at the national level - a rare phenomenon in itself - without a Bhutto in parliament or government.

Is this resilience? Or a new life for an old party to re-invent itself for a new age? Bilawal’s job description of leading Pakistan’s biggest party - which has come to power in elections more times than any other party (in 1970, 1977, 1988, 2003 and 2008) - isn’t new. At age 19, he was appointed chairman after his mother was tragically assassinated in 2007. His father has kept the seat warm for him as co-chairman while Bilawal completed his studies at Oxford.

In fact, Bilawal is still ineligible to participate in elections and run for a seat of the National Assembly until September 2013 when he attains the age of 25 in the month that Zardari’s five-year tenure as a democratically elected president expires. However, age is no bar for him to do politics, run an election campaign and to whip up his party in shape for the electoral battle that has already unfolded.

Dynastic politics may not be desirable but in Pakistan dynasties have been successfully used to blunt the Establishment’s relentless efforts to discredit and break up parties. In this context, focusing on Bilawal and not the PPP would be missing the wood for the trees. It would be a mistake to view Bilawal formal launching himself into practical and full -time politics as merely his personal matter.

His entry into politics should be viewed as a new chapter in PPP’s politics and the party’s unfolding strategy to shape its responses to new challenges in an old Pakistan.

Finishing its stint in power, the new challenge for PPP is threefold. The first challenge is to go into election for a comeback, which is easier said than done for any party in harsh, cynical Pakistan. The PPP has never been allowed to do this despite the one time in 1977 when it was re-elected with a majority but ended up losing out to a martial law that devoured its founding chairman and imposed the long, harrowing rule of a dictator.

The second challenge is to complete the process of leadership transition begun with Bilawal’s symbolic appointment as chairman in an emergency in 2008 after the latest assassination of a Bhutto. His father and aides have managed to thwart all attempts at sabotaging the party and its government many times.

The third challenge is to stay relevant as there are more Pakistanis now born after the party was formed than those before it and there are more first time voters now than when the last chairperson, Benazir, wooed and won voters to her side to vote for PPP in 1993, making her prime minister. Making matters worse, a majority of voters aren’t old enough to have seen the party and its last leader Benazir and understood the messy transition of the 1990s.

If Pakistan is to be a perpetual democracy, then political parties must be respected and protected - especially those that espouse inclusivity, liberalism and egalitarianism in a multi-national, multi-ethnic, multi-linguist, multi-sectarian state as ours. Without political parties that have large footprints and which represent the interests of a wide-based plurality such as Pakistan’s, the country will flounder by making it easier for non-democratic forces to force themselves upon a majority of the citizens.

Parties - not just PPP but those that have large bodies of followers such as Nawaz Sharif’s PML-N, Asfandyar Wali’s ANP and Altaf Hussain’s MQM, among others - are important for Pakistan’s democratic project as they embody collective will and are the closest power tool that comes to a communal endeavour to establish an environment in which groups of people believe they will thrive and prosper.

But it’s a fair question to ask if Bilawal is really the right leader for PPP at this point in time? After all, people vote for political parties that have leaders they believe can deliver for them and keep their word. Voters trust their leaders as they trust their own family members. If they fail, they lose their right to lead. The political parties are fuelled by voters’ trust and must be accountable for keeping their promises and delivering on the mandate given them.

For Bilawal, as for Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Benazir Bhutto, it is going to be anything but easy. In today’s Pakistan you can’t make promises of facilitating a new social contract and not keep these promises and get away with it.

The new Pakistan is not about whether Bhutto and Benazir’s murders can be avenged or not, it’s about what is right or wrong for the people who are sending parties to power to exercise it on their behalf, not use it for their personal privilege. They want leaders who lead by example, not just operate on rhetoric.

If Bilawal cannot grasp this simple fact and does not focus on the raison d’etre of being in office, the party is over. He certainly has precedents he needs to emulate right at home. His grandfather and mother earned their stripes by staying the course even at the cost of their lives for democracy. Not just for the party but for Pakistan. Bilawal will have to earn his stripes the hard way.

♦ The writer is freelance journalist based in Islamabad. He can be reached at [email protected]