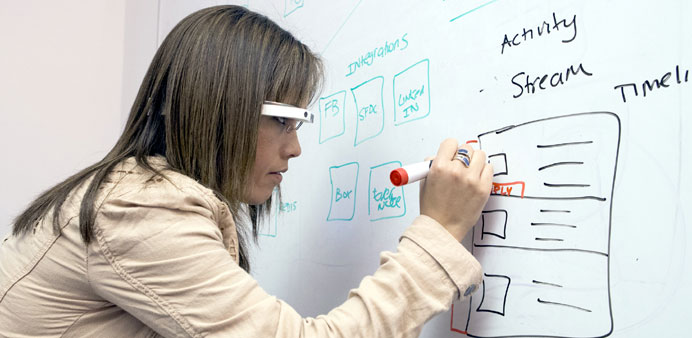

Glass resembles a pair of high-tech eyeglasses, but without lenses: Its lightweight frame rests on the ears and nose, suspending a small prism in the upper right corner of a wearer’s field of vision. By Brandon Bailey Back when she was in college, software developer Monica Wilkinson says, she used to dream of “being able to carry a computer in my head,” instead of lugging her books and laptop all over campus. As she tried out her new Google Glass recently, Wilkinson said, it felt like that fanciful idea had become real. Dan McLaughlin, an engineer and photography buff, has been using his new Glass to take pictures without fumbling for his camera. Tech business consultant Lisa Oshima said she likes hearing turn-by-turn directions from Glass as she walks to client meetings in downtown Palo Alto, California. Startup executive Brandon Allgood, meanwhile, has learned to remove his Glass headset before sitting down to dinner with his wife. The four San Francisco Bay Area tech workers are among the first non-Google employees to get their own early model of Glass, after paying $1,500 for the visor-like, wearable computer that’s already got critics fretting over potential violations of privacy and etiquette — even as enthusiasts proclaim it could change the way people interact with technology. “The human body has a lot of limitations. I see this as a way to enhance our bodies,” said Wilkinson, 36, who is head of engineering at San Francisco startup Crushpath. “The future can sometimes be a little bit scary,” she added, conceding that some people are uncomfortable with the new technology. “But I see Glass as a way to stay connected, to capture more moments and get answers more quickly.” Glass resembles a pair of high-tech eyeglasses, but without lenses: Its lightweight frame rests on the ears and nose, suspending a small prism in the upper right corner of a wearer’s field of vision. The prism displays pictures, video or text, including e-mails, directions from Google’s navigation service and answers to Internet search queries. Along with a digital camera, Glass has a tiny touch pad built into one earpiece and a microphone to pick up voice commands. The earpiece uses “bone conduction” to deliver sound by vibrating against the wearer’s skull. Glass connects to the Internet through Wi-Fi or a Bluetooth link to the user’s smartphone. So far, early adopters say they’ve received curious stares and friendly questions, but no hostile reactions while wearing something that resembles a prop from ‘Star Trek’ around the tech-friendly Bay Area. Construction workers and mass-transit riders have told Oshima they think Glass is cool. And despite critics’ fears that Glass wearers might surreptitiously record someone’s private moment — or use Glass to rudely surf the Web while someone is talking to them — Wilkinson and the others predict those concerns will subside as Glass owners develop their own etiquette. Allgood, for example, said he removes the headset in the evening because his wife is less enthusiastic about new technology than he is. He has also made a practice of sliding it to the top of his head when he enters a men’s restroom, so the camera is pointed at the ceiling and no one gets alarmed. “There probably is going to be some drama at some point,” Wilkinson predicted. But she noted that non-Glass wearers can tell when Glass is recording, because its tiny screen lights up. “If people look apprehensive,” she added, “I just tell them, ‘I’m not recording you.’ “ Google doesn’t expect to sell Glass on the mass market before next year. It’s unlikely to be a big moneymaker right away; analysts say Google must lower the price to appeal to more consumers. But CEO Larry Page has said he views Glass as the first in a wave of new computer devices, and others say it makes sense for Google to get in front of that trend. The introduction of Glass “is a watershed moment that will lead to the Internet being available more often” through a variety of wearable gadgets, Macquarie Equities analyst Ben Schachter wrote in a report last month. Anything that increases Internet use, he added, is good business for Google and other companies that make money by delivering ads and services online. For now, Wilkinson and others in what Google calls the “Glass Explorers” programme are among the first few hundred people to get their hands on the gadget. They’re software developers and tech enthusiasts who signed onto a waiting list last summer, after a blockbuster demonstration by a troop of Glass-wearing sky divers at Google’s annual software conference. McLaughlin, a 46-year-old Agilent engineer, said he has been wearing his Glass throughout the day. He said it’s convenient for checking e-mail, but as an amateur photographer, McLaughlin especially loves taking photos by voice command. He and his 10-year-old son have made up a game where they lean their heads together and — when his son says the magic words, “OK Glass, take a picture” — the device on McLaughlin’s forehead snaps a photo that’s automatically uploaded to his online Google+ account. Wilkinson has been wearing hers during video conferences with colleagues in other offices, writing code on a whiteboard and using Glass to show them the board as she is looking at it. She also uploaded a video showing what she sees as she volleys a ball at her tennis club. For Allgood, the “killer app” on Glass is Google Now, an online service that automatically delivers information tailored to a user’s recent searches and activity on Google. If he has a business meeting listed on his Google calendar, for example, Glass will alert Allgood when it’s time to go to the meeting and show him directions and traffic updates. The same information is available on a smartphone, but it’s more convenient when it pops up on Glass, said Allgood, a 38-year-old executive at the health technology company Numerate, who says he played cyborg games and daydreamed about “retinal implants” as a youngster. Allgood said he believes Google has only scratched the surface in thinking of uses for Glass. The company is encouraging independent developers to build a variety of apps, which experts say will help make Glass more appealing to ordinary consumers. And Oshima, whose consulting firm, Socialize Mobilize, works with app developers, says she knows several who are eager to get started. For those who say Glass seems like a nonessential toy, she added, “I remember when people used to say that about mobile phones. There was a time when people would tell me that social networking was “kids’ stuff” and that adults would never use Twitter or Facebook.” — San Jose Mercury News/MCT * A team member (right) can see what software developer Monica Wilkinson (above) is writing on a white board while she wears Google Glass at Crushpath in San Francisco. The electronic glasses are not available to the public yet, but some developers have been able to buy them to prepare apps.

Cover photograph: Software developer Monica Wilkinson tries out the Google Glass. Though critics fear that Glass wearers might surreptitiously record someone’s private moment — Wilkinson and the others predict those concerns will subside as Glass owners develop their own etiquette.