By Steff Gaulter

|

|

Water is one of the most precious resources on this planet. With the ever-increasing population, the demand for it can only intensify. Already people are speculating that in the future wars are likely to be fought over water sources.

In Qatar, where there are no rivers and precious little rainwater, we have to look at alternative sources for our water supply. In fact, given the exploding population, we are very fortunate that the country is so wealthy. This ensures that desalination plants, a very expensive way of producing water, can be used to produce clean water from the sea. Although many people choose not to drink desalinated water, preferring bottled water instead, the water from the taps is reliable and of good quality.

Other countries are trying to find cheaper alternatives to their expanding water needs. In parts of the globe with sufficient rainfall, it is possible to install water butts in gardens. This is probably the most simple form of water harvesting, but in some parts of the world it’s taken far more seriously. If there isn’t sufficient water falling from the clouds, scientists have developed ways of extracting water from the air instead.

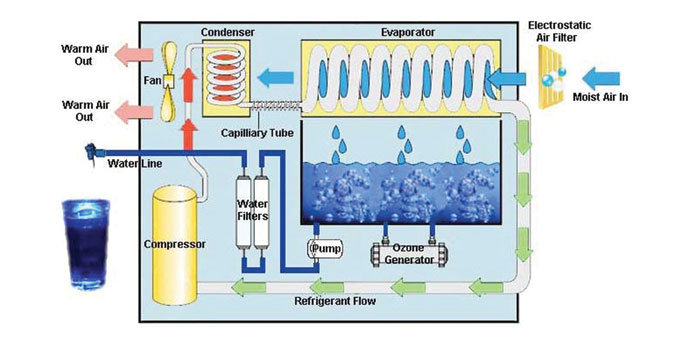

There are various methods of doing this, but essentially the idea is to cool the air enough to make the water vapour in it condense. The most simplistic method is to hang out a plastic net. Water vapour will condense onto the net, and this water then flows towards the ground and can be collected in a little reservoir.

This simple method can be surprisingly efficient: in El Tofo, in northern Chile, 30% of all the humidity that passes through the nets is collected. This produces between five and 13 litres of water per square metre per day.

Chile and Peru are the real pioneers of harvesting water from the air because they have the perfect climate for it. The ocean current which wells up on the west coast of South America is very cold. This cold water suppresses the rainfall, and cools the air so much that the coastline is shrouded under a thick layer of fog for over 200 days of the year.

The Peruvian capital, Lima, is one of the locations that exists in this foggy, desert climate. The city is home to over 7mn people, but receives just 13mm (0.5 inches) of rain per year, far less than Doha’s average of 75mm (3 inches). The city relies on three rivers for its water supply, which flow down from the mountains. However, the source of this water, the glaciers, has shrunk between 30 and 50% since the 1970s. It’s already estimated that over 1mn residents in Lima don’t have access to running water, and instead have to pay extortionate rates to private water suppliers.

Working together, a university and advertising agency have recently developed a new way of harvesting water. A giant advertising hoarding captures the humidity in the air, then purifies it to create drinking water. It’s not entirely energy free, and does require electricity, but nowhere near the amount of energy that a desalination plant requires.

In the first three months of operation the billboard produced 9,450 litres of water (about 2,500 US gallons), enough to supply water to hundreds of families. There are hopes that more billboards could be constructed in different parts of the city, to provide yet more fresh water.

Chile and Peru may be the pioneers of harvesting water from the air, but they are not alone. The south coast of Oman also sees a lot of fog. Like the west coast of South America, there is also a cold current that wells up along the Omani coast. This upwelling only happens in the summertime, when the coast, including the city of Salalah, is shrouded in fog. This does put a limit on when the water harvesting can take place, but during the three summer months, the simple net technique of collecting water produces an impressive 30 litres of water per square metre per day.

In Qatar, we clearly don’t have endless fog, but water harvesting may not be as hopeless as you might think. Fog can only form with humidity of over 95%, but water harvesting can take place if the humidity is over 69%, meaning you don’t have to be able to see the moisture in the air in order to harvest it.

At the moment, with that howling northwesterly, our air is clearly very dry, but I counted the number of days that water harvesting would have been possible in Doha last year and it was 218, approximately two-thirds of the year. Barely any water could be harvested between April and mid-July, but after this the dry Shamal wind eases. The weather becomes more humid in Doha, and that humidity stays with us through the autumn and into the winter.

However, collecting water from air isn’t quite as straight-forward as looking at the humidity readings. For a start humidity increases during the night when the temperatures drop, so it’s important to realise that water collecting wouldn’t happen throughout the day. Also you have to take care when choosing where to put the net. Clearly it can only work if air flows through it, and as winds blow from different directions, it’s clear that water would not be collected all the time.

Despite the limitations, it may be worth examining the potential of water harvesting in Qatar, but it’s also worth remembering that there is a consequence to every action. If you take the humidity out of the air, the air will be drier.

This will lead to an increase in temperature during the day and a decrease during the night. Whilst that might sound like a benefit, the long-term effects on the landscape might be more detrimental; a drier country could well be a dustier one.

(The author is Senior Weather Presenter at Al Jazeera English channel. She can be contacted on [email protected]

or on Twitter at @WeatherSteff)