By Larry Gordon

On the front of the cinder-block library on Cesar Chavez Avenue in East Los Angeles, near a building supplies warehouse and an auto parts shop, a rainbow-coloured mural shows children reading books beneath lush trees. Around the corner, a squat beige drop box awaits returned books and videos.

Only the name, the Anthony Quinn Public Library, gives a clue that this isn’t your normal neighbourhood branch of the Los Angeles County library system.

Inside, an oil portrait of the late actor smiles down on middle school students doing homework in the reading room. A suit of armour stands guard in a Plexiglas case, a gift to Quinn from his mentor, John Barrymore, who had worn it in a stage production of Richard III. Zorba the Greek’s hat, a memento of Quinn’s signature role, is embossed in bronze in another case.

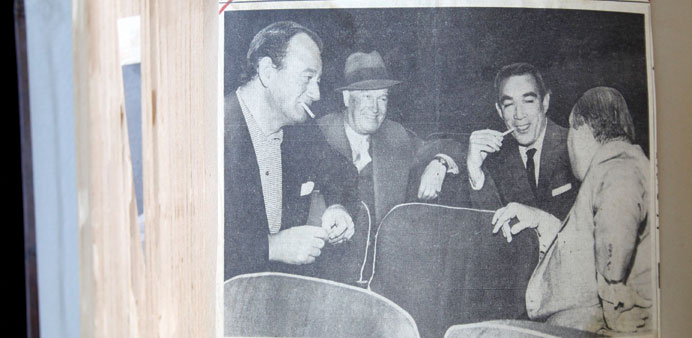

Locked up in the community room’s cabinet, an estimated 100 cardboard boxes hold a personal archive of the first Mexican-American actor to win an Academy Award. Scrapbooks of clippings go back to a 1939 ad for his film Island of Lost Men, with ticket prices at 10 cents. A pile of photos shows life on the set of Lawrence of Arabia. A loose-leaf phone book contains numbers for Bill Cosby and Liza Minnelli, along with dentists and limo drivers.

Built on the site of the home where Quinn grew up, the library is an unlikely repository of movie star glamour. But it also offers a glimpse of how Hollywood treated ethnic minorities.

“It has incredible value for writing the history of Latinos in the US film industry,” said USC film school professor Laura Serna, an expert on Latino cinema. She considers the Mexican-born Quinn one of the greatest Latino stars even if his surname came from an Irish grandfather and his roles included Italians, Arabs, Native Americans and, most famously, Greeks.

Even through such mundane objects as expense accounts and contracts, Serna said, the collection can provide details about how actors “negotiated the ethnic and class divides in an arena in which Mexican Americans were generally marginalised — except, of course, as a possible market for the industry’s wares.”

The library branch was named for Quinn 30 years ago, and, in 1987, the actor donated the large collection of personal papers, scrapbooks, movie scripts and financial documents.

Yet for all the time since, the 2,000 or so items were rarely visited and remained stored without proper safeguards. Many Hollywood historians didn’t know of the archive’s existence and, without an inventory and sufficient library staff, it was difficult to determine what was there, let alone what was significant.

Now that is about to change. Because of a $6,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the collection was recently reviewed by preservationists who recommended ways to ensure the archive’s safety. Library officials say that they are about to improve the storage and create a cataloging system and, if more funding becomes available, scan important items for online researchers.

Besides the insights into Quinn’s life, the materials “provide documentation on numerous other prominent figures in the entertainment industry, as well as on the business and inner workings of feature filmmaking during the mid- to late 20th century,” declared the NEH award citation.

David Roman, a USC professor of English and American Studies, is one of the few scholars to have explored the Quinn material. He dug into it six years ago to research Quinn’s Broadway stage career in the 1940s and how “a Mexican-born actor who grew up in poverty in East Los Angeles took on one of the most iconic roles in the American theatre.”

He was referring to how Quinn succeeded Marlon Brando as the male lead in the Broadway production of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. The library materials, he recalled, “helped me get a fuller sense of his life as an actor.” But Roman said he was shocked at how jumbled the Quinn papers were and how vulnerable they seemed, with some old items already damaged.

That is not all of Quinn’s collection. Many other writings, books, memorabilia and hundreds of the paintings and sculptures he produced remain at the Rhode Island home he shared with his third wife, Katherine, and their two children.

“He never said he wanted a museum or library or a building to immortalise who he was,” Katherine Quinn said recently during a visit to Los Angeles, including a stop at the library. “He was too busy living his life.”

Quinn was born in Chihuahua, Mexico, and his parents had fought in the Mexican Revolution before moving to Texas and later California, picking crops for a while before settling in Los Angeles.

Although he sometimes played Latino characters, such as the patriarch in The Children of Sanchez, he had a portfolio of earthy pan-ethnic roles, including an Italian circus strongman in La Strada, a Ukrainian pope in The Shoes of the Fisherman, an Arab warlord in Lawrence of Arabia and several Greeks beyond his famous turn in Zorba.

His two Oscars, both as best supporting actor, were for Viva Zapata! in 1952 and four years later for his portrayal of the painter Paul Gauguin in Lust for Life. He later was nominated as lead actor twice, for 1957’s Wild Is the Wind and for 1964’s Zorba but did not win.

In his two autobiographies and in interviews, Quinn discussed ethnic bias in his early career as he entered elite Hollywood circles through his first marriage, to the daughter of powerful producer and director Cecil B DeMille. And he said he faced some skepticism from the other side too.

“With a name like Quinn, I wasn’t totally accepted by the Mexican community in those days, and as a Mexican I wasn’t accepted as an American,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1981. “So as a kid, I just decided, well a plague on both your houses, I’ll just become a world citizen. So that’s what I did. Acting is my nationality.”

Beyond illuminating the life of the actor, who died in 2001 at the age of 86, the East Los Angeles archive shows how the entertainment industry operated on typewritten documents and personal letters in an era before e-mail and cellphones, librarian Hernandez said.

One box, for example contains many pre-production memos for The Magus, a 1968 flop that was shot partly in Spain. There are travel arrangements, forms for medical insurance, letters about costume fittings and a ledger listing Quinn’s expenses, down to handkerchiefs, chocolates, Band-Aids and sponges.

Another carton holds a 1969 handwritten letter from British star Sir John Gielgud, inviting Quinn to join the cast of a movie version of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, which was never filmed. Makeup drawings show Quinn’s transformation into a Mongol emperor for the 1965 film Marco the Magnificent.

Honours are in the collection too, such as a 1987 letter on White House stationery from President Ronald Reagan congratulating Quinn on an award from the Foreign Press Association. But insecurity is apparent in copies of letters: In 1984, when Quinn was starring in a stage musical version of Zorba, he wrote to Jack Valenti, president of the Motion Picture Association of America, about how he had waited for a backstage visit that never occurred:

“I suffered for weeks thinking you found my performance so deplorable that you were embarrassed to face me. Let me know the next time you are coming. I’ll try harder.”— Los Angeles Times/MCT