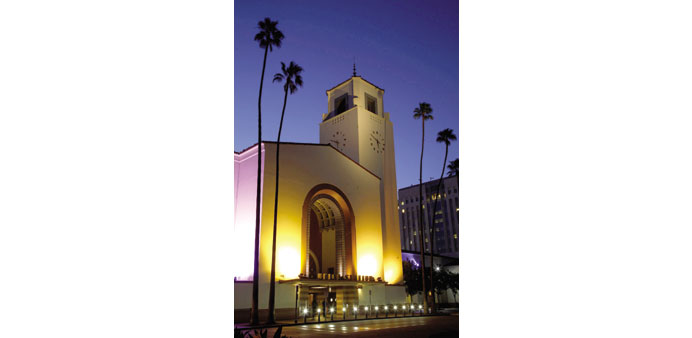

It’s a star in its own right, this building — a strange, graceful LA marriage of Spanish Colonial and Streamline Moderne styles — born in 1939, the last of the great American train stations.

By Christopher Reynolds

Many movies have been shot at Los Angeles Union Station. But none can match the one you start filming in your head the moment you arrive from Alameda Street.

You fade in on the feet of a trendy young commuter, ear buds in place, rushing along the well-buffed tiled floor. The camera tilts up to reveal a homeless man dozing in one of the station’s original leather-and-mahogany armchairs. You see a high, heavy chandelier, a grand arch, beams, stencil work.

It’s a star in its own right, this building — a strange, graceful LA marriage of Spanish Colonial and Streamline Moderne styles — born in 1939, the last of the great American train stations. After a dismal slog through the late 20th century, Union Station is busier than ever, with about 10 times the traffic it had in its prosperous early years. Chances are it will soon be busier.

If you do your travelling by car and plane, you haven’t seen the station in years, haven’t harnessed your inner Hitchcock, haven’t wondered where to hand off the mysterious suitcase, where the adulterers get down to business, where to stage the murder.

To the right, where the pay phones once were, you’ll find the Traxx bar, ripe for eavesdropping.

Just across the arcade, you have the station’s original restaurant, a Harvey House designed by Southwestern architect Mary Colter. It’s been closed (except for film shoots and special events) for decades.

To the left, you can lean on a movable counter leftover from either a Night Court TV shoot or a Blade Runner movie shoot, depending on whom you ask. And from there you see the station’s enormous and idle ticket concourse, suitable for occupation by the Phantom of the Coast Starlight.

Los Angeles Times photographer Mark Boster and I prowled the station for several days recently to finish our yearlong series on iconic locations, Postcards From the West. (You can see the first half-dozen at latimes.com/postcards.) I was standing near the old ticket concourse, trying to recall plot points of Union Station (1950, starring William Holden) and Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982, starring Steve Martin), when unscripted reality interrupted.

“My wife’s had surgery!” an enraged Amtrak customer yelled at a security guard. “What is this, a museum or a ... transportation centre? You guys are pathetic! There’s no help!”

The security guard stayed cool; the man stormed off; the human ebb and flow resumed.

Grandeur, grit, sepia light, flawed humanity — and that’s before you even get to Wetzel’s Pretzels. That food stand turns up, along with a sweet-smelling Subway, Starbucks, See’s Candies, Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream and the convenience shop Famima, in the jumbled departure area just beyond the waiting room and before the long passage to the train platforms.

This is far more commercial life than the terminal saw from the 1960s to the ’90s. Daily traffic is up to 60,000 to 75,000 commuters and travellers, depending on who’s estimating. But as Metropolitan Transportation Authority officials acknowledge, the departure area

could use better signage. (Amtrak and Metrolink do have motorised carts to carry travellers who have a disability, but station signs don’t make that clear or explain how to summon one.)

If you walk down the long passage past the train platforms and under the tracks, you reach the station’s east portal, built in the 1990s. Your reward for roaming waits above: a striking, 80-foot-wide multicultural mural of LA faces by Richard Wyatt, with an olive-skinned girl in a green blouse at centre.

To me, she’s Our Lady of the Trains. Above her, the sun shines through a geometrically patterned skylight dome. Without leaving the station, you’ve just travelled from one end of the 20th century to the other.

Beyond the station itself, things get tricky for a traveller, and many are put off by its proximity to the 101 Freeway, the county jail and the many panhandlers near Olvera Street. But the resurgence of downtown Los Angeles has brought new options beyond the usual Olvera Street shuffle. Walk several blocks from the station — or take a one-stop subway ride — and you can browse vintage vinyl and contemporary art in Chinatown, drink a $12 Asian Zombie under a string of lights in Little Tokyo or picnic on the grass of well-tended Grand Park, just across the street from City Hall.

Since the Metropolitan Transportation Authority bought Union Station in 2011, plans are afoot for more changes. Ken Pratt, Union Station’s director of property management, said he has been courting prospective bar and restaurant tenants for the Harvey House. In as little as 18 months, Pratt said, “some inventive, eclectic, well-heeled restaurateur is going to come in here and do something marvelous.”

Meanwhile, the MTA this year added a red-coated passenger assistance staff to answer questions. The MTA has also closed the station to non-passengers between 1 and 4am to give janitors more room and to discourage homeless people from treating the station as base camp. In some not-so-historic second-story space above Amtrak’s ticket sales window, the rail line has quietly opened the private Metropolitan Lounge for its business-class and sleeping-compartment passengers.

In public spaces, there will be more movie nights and more live music, Pratt said, perhaps some artisan food services at the east portal in the next year, perhaps another restaurant in the now-idle space where Union Bagel once operated.

In the longer term, MTA executives are developing a master plan that would preserve the historical structure but add retail space, reroute the flow of bus traffic, allow for the arrival of a bullet-train connection to San Francisco by 2029 (if that costly, controversial project is completed) and improve transitions between the station and the neighborhood.

Executives say the MTA may even buy and knock down the privately owned Mozaic apartment buildings, an undistinguished complex next door that was built in 2006.

“We would be fine with that,” said Adrian Scott Fine, Los Angeles Conservancy advocacy director. As for the MTA’s larger ambitions? “The devil will be in the details.”

But these changes could be years away, and plenty of ambitious Union Station plans have been floated and abandoned over the decades. Instead of holding your breath, savor the place as it is, grab one of those comfortable chairs, watch the passenger parade and polish your second act.

For instance, that Night Court/Blade Runner counter in the vestibule? Definitely big enough to hold a corpse.— Los Angeles Times/MCT

KEEPING TRACK OVER 7 DECADES

LA’s Union Station, the “last of the great train stations,” has been moving people and freight for more than seven decades.

May 1939: Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal opens, linking the Santa Fe, Southern Pacific and Union Pacific railroad systems, which used to operate separate stations. To make room for the new station, much of the city’s original Chinatown was levelled. The station’s design, by the father-son architect team of John and Donald Parkinson, mixes Streamline Moderne and Spanish Colonial styles with Moorish accents. The station’s first timetable lists 33 arrivals and 33 departures daily.

1940s: Civilian traffic reaches an estimated 6,000 people a day. During World War II, traffic is far greater as troops are mobilised.

1950s: As automobile and air travel increases, the station becomes known as “the last of the great train stations” in the US.

1966: After decades of relying on trains, the Postal Service shifts to using planes and buses. Passenger traffic dwindles too.

1967: The station’s slowest year, with just 15 trains in and 15 out a day.

1971: Congress creates Amtrak to take over passenger service from rail companies. At Union Station, passenger traffic remains thin.

1992: Catellus, a development company formed from real estate holdings of the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific railroads, begins restoration of the station. Also, Metrolink begins regional commuter rail service with Union Station as its hub, carrying 5,000 passengers on its first day.

1993: The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority opens the first 4.4 miles of the Metro Red Line, which will eventually connect Union Station to downtown Los Angeles, Hollywood and North Hollywood.

1995-1998: Gateway Transit Center, renamed Patsaouras Transit Plaza, opens at Union Station as a hub for bus service. Catellus sells station-adjacent property to several buyers, including the MTA, which builds a 26-story headquarters. Inside the station, owner-chef Tara Thomas’ Traxx Restaurant opens.

2003: MTA opens a Metro Gold Line light-rail stop, connecting the station with Pasadena.

2005: Catellus merges with industrial developer Prologis.

2011: The MTA buys Union Station and its 38-acre property for $75 million, making the landmark property public for the first time.

2013: Weekday traffic is about 10 times what it was in the 1940s: 60,000 people by some estimates, 75,000 by others. About 60 movies, TV shows and ads a year are filmed on-site.