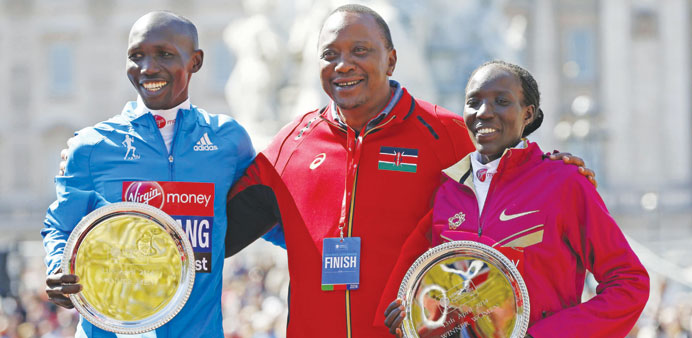

The winners of both the men’s and women’s London Marathon, Kenyans Wilson Kipsang (L) and Edna Kiplagat (R), pose for a photograph with Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta in London last Sunday.

By Sean Ingle/The Guardian

One London Marathon official suggested 650,000 had lined the course but amid all the shuffling and shunting, the cheers and bunting, how could you possibly tell? You might as well have licked a finger and shouted the largest number in your head. It would have been no less crazy than a man running 26.2 miles with a fridge on his back as someone did on Sunday.

No one, however, would dispute that this year’s London Marathon was a major event. Of course, Mo Farah’s appearance was a significant factor, but something Haile Gebrselassie the great Ethiopian and pacemaker for the race said in the buildup stuck too. That while the big city marathons are having a moment, track and field is falling back. Gebrselassie’s analysis was simple but cutting: depressed global TV audiences should be a concern for the IAAF, athletics is too dependent on Usain Bolt and the sport needed new ideas.

“This is the 21st century,” he said. “We have to give people what they like. Many stadiums are full because of Bolt. But if you don’t have him in the next two-to-three years we will be in trouble. We need new ideas to attract audiences and sponsors. A crazy idea. A new tactic.”

Gebrselassie was only articulating what others believe privately. We know people come for the Olympics and, to a lesser extent, the World Championships and Diamond League meetings. But athletics matters less than it once did.

Partly, this is owing to football’s mushrooming dominance. In the 1980s, sport on British TV was rationed to four major stations. Now, providing you have the money to afford satellite, there is an unlimited 24-hour multichannel buffet cart. Most vote football with their Sky remote.

A large number of positives have also been a major negative. After Ben Johnson tested positive for stanozolol who could be sure the fantastical wasn’t fraudulent? Johnson’s coach Charlie Francis subsequently became the Val Valentino of the 100m: the conjuror who revealed the secrets of the magic circle.

Yet Gebrselassie is right. Track and field can learn from the road. The London Marathon, for instance, nails the essentials. This year both men’s and women’s races were at least as strong as an Olympic final. The casual fan might not be able to distinguish between Geoffrey Mutai and Emmanuel Mutai. But a field containing the world record holder, Olympic and world champion and reigning champion is a shorthand for those watching. It tells them it matters. And the wildcards of Farah and Tirunesh Dibaba added stardust and further stories.

Of course, the marathon has advantages. The top athletes do not race the distance very often -- usually no more than three times a year so when they do it’s for real. They want either a win or a personal best.

It is free to watch too -- but look at the Paris Marathon, which is often observed in church-like silence. While we should not underestimate the value of people watching an event that goes past their house or through their city, the organisers are smart. There are 90 bands to provide atmosphere, while every pub en route is given prizes to give out. It is not just the race that provides the spectacle.

Track and field should be bolder. Why not try combined male and female relays? Or find ways of making the field events shorter yet more focused? Why not three throws or jumps instead of six, but ensure the denouement is the only thing people are watching?

Farah against Bolt over 600m? “That’s what I want to watch!” said Gebrselassie, smiling. Would it be a publicity stunt? Definitely. Would you watch it, read about it, talk about it? Most probably.

London Marathon’s head of international relations, Dave Bedford, agrees but he is singing from an old song sheet. In 1973, he told the Guardian:

“I want to see pursuit races in athletics like those in cycling.” In 1993, he was telling the same paper how he admired the way World Wrestling Entertainment marketed its product.

Whether you agree with the likes of Bedford or Gebrselassie or not, there are obvious dangers of relying on one big star. In the US the TV ratings for the first two days of the Masters were reportedly down 30% because Tiger Woods was not playing. You suspect Bolt’s absence from main events would have a similar impact. Yet if Lionel Messi were to retire tomorrow, it might deeply sting Barcelona but it would barely scratch football’s popularity.

Bedford believes athletics needs more characters. He certainly can talk. In the 1970s he was the sport’s own Ziggy Stardust, with his distinctive red socks, a moustache that wrapped around his mouth like a horseshoe and his pointed riffs at officialdom.

He was talented enough to break the 10,000m world record but also spoke his mind. And who would not want to read about someone who ran 200 miles a week while holding down a job and drinking two pints every night? Few elite runners enjoy such excesses these days but even if they did, would they ever tell us? As Bedford says: “The pressure is on them to toe the line, not to rock the boat, from their sponsors. Only a few athletes appear to be able to break out of that.”