“What is certain to come is the Internet of things,” Alexander Fauck, managing director of Technologiefabrik, tells PeterZschunke, meaning everyday gadgets linked to the Internet

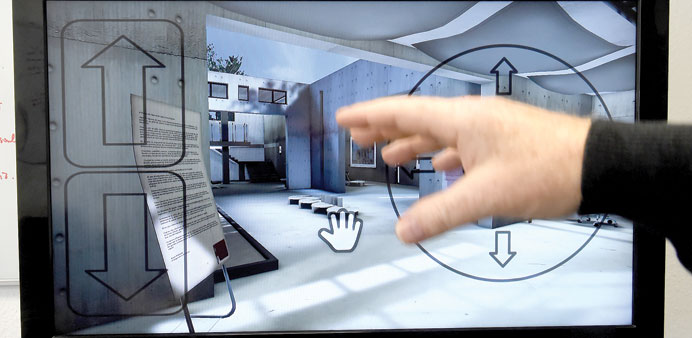

The dream of launching the next technological breakthrough from a garage, a la Apple or Google, never seems to die. The eyes of Friedrich and Jens Schick light up when they are demonstrating their “spacepad,” a room where software can be guided with one’s hands.

The demonstration is taking place at the Karlsruhe Technologiefabrik, or technology factory, located in a former German sewing machine plant that closed down in 1981.

“We measure movement. That what’s new,” Friedrich Schick explains, while operating a system comprised of a computer and two cameras. “With this, you can interact with a display from outdoors.”

Their idea: a computer could be set up in a store window. Passers-by could operate the display through the plateglass if they needed more information about products on sale. That would be a benefit in the night, when the shop is closed, or where vandalism is rife.

The father-and-son Schick team have founded the Myestro Interactive company. It’s one of 70 start-up firms in the Technologiefabrik. Their development office is even smaller than a garage, but this doesn’t bother the inventors.

“There is an innovative atmosphere here in Karlsruhe,” says Jens, 25. “Many new things were started here. We’re in the right place.”

Alexander Fauck, managing director of Technologiefabrik, explains the idea behind it. “We wanted to create a centre for young companies which are in the critical early years of independence,” he said.

The centre, established in 1983, was the second of its kind in Germany after one in Berlin. Fauck said that with the sponsorship of the German Chamber of Industry and Trade (IHK), the centre has helped more than 340 start-up companies, creating some 6,000 jobs.

“We don’t take just anybody. We’re very selective,” Fauck says. “A precondition for being taken on is that something is being developed, meaning that it is not purely services being offered.”

Between 70 and 80 per cent of the firms are involved in the information technology sector. Current trends include cloud computing-based IT applications from the Internet, as well as “big data” analytics as well as developments in image recognition.

The latter is Myestro’s field.

“What is certain to come is the internet of things,” Fauck says, meaning everyday gadgets linked to the internet.

The rent in the Technologiefabrik is below normal market levels. The centre also supports the start-ups with courses in sales and marketing, and above all by offering comprehensive networking.

Firms stay an average of five to eight years in the Karlsruhe centre. But some leave it after only two years.

One company that succeeded is a software firm BrandMaker, which offers marketing software.

“The first few years in the Technologiefabrik were very good for us as a young company,” recalls chairman Mirko Holzer. Karlsruhe is “an outstanding site to found an IT company,” he adds. Qualified personnel are available, thanks to the nearby Polytechnical College.

Demand for personnel is now outstripping the supply.

As was the case at BrandMaker, the business models of the start-ups are mainly oriented towards offering products to business. That’s how the Karlsruhe centre differs from that in Berlin, the largest of its kind in Germany, where apps for mobile phones and gadgets play the main role.

Helping to pave the difficult road between an idea and founding a start-up company in Karslruhe is the Karlsruhe Institute for Technology (KIT), with its in-house institute for entrepreneurship, technology management and innovation (EnTechnon).

“What we’re lacking is a local risk capital fund,” notes Matthias Hornberger, chief financial officer of the Karlsruhe investment company Kizoo Technology Capital. Now, such investment funds from the United States are starting to look at Germany.

“Basically, we have an atmosphere in Germany that is not particularly friendly towards start-ups,” he says. One obstacle: tax laws that hardly encourage start-ups.

Also missing is a “culture of failure,” such as is found in the United States, where people understand that there’s always a risk of failure in trying to succeed.

“Failure is part of founding something,” says Michael Kaiser, head of the city of Karlsruhe’s business promotion company. “This experience can trigger very many processes which then can lead to success.”

The banks here have fostered the notion that failure is proof of incompetency, and so they refuse to provide credit to a new venture.

Myestro’s technology, in which software can be guided by the movement of hands without any touching, is a fascinating one — but difficult to market, Hornberger admits. The Myestro founders have noticed the reticence of investors.

They plan to strengthen their marketing efforts once they have developed a prototype.

There are already some initial customers, but company founder Jens Schick remains realistic: “It’s a huge challenge to enter a market that does not even exist yet.” — DPA