Verdon Gorge — French version of the Grand Canyon — is little known outside the country but offers a picturesque hike for adventurers. By Steve Brandt

We stood on the edge of the precipice, stunned momentarily by a sign we had not anticipated when we arrived for our long-planned plunge into the Gorges du Verdon, the French version of the Grand Canyon near Provence.

In dire terms, the sign warned of hazards ahead, including a sudden rush of l’eau that could be released from the reservoir up the valley. We were shocked by the thought of having to forgo the hike that had been on our bucket list for a dozen years, 10 miles through what’s considered one of Europe’s most spectacular gorges.

Then we spied the small knots of hikers descending the switchbacks toward the valley floor a half-mile below. The sign warned of dangers, but it didn’t bar entry.

Truth be told, the sign wasn’t my only reason for misgivings. We had arrived at the gorge by coincidence on Lynda’s 63rd birthday. Although she’s a regular on the YMCA treadmills, the years have left her with an increasingly troublesome hip alternately diagnosed as arthritis and bursitis. It once seized up just before a five-day hike through the English Cotswolds, then fortunately and just as mysteriously vanished after a ride on the broad back of an Icelandic pony during a stop on the flight over. I imagined myself halfway through the hike, stranded miles from help with a hiking partner suffering from bone-on-bone pain.

I gently suggested that perhaps a less challenging hike might be prudent.

“Oh, honey. I’d be so disappointed if we gave up before we started,” my wife replied, proving that I’d underestimated her determination.

She popped a couple of prophylactic ibuprofen, extended her hiking poles and we descended.

We entered a chasm cut through eons’ worth of grey limestone by a river sometimes milky with sediment, sometimes an exquisite turquoise. The massive cliffs were punctuated by less-weathered salmon splashes where the rock had split, plus washes of dark mineral seepage and fringes of vegetation. The micro-climes ranged from semi-alpine on the warm north face to mossy semitropical lushness in shady portions of the flood plain.

This variety has made the gorge that extends for miles beyond our hike a beacon for scenery-seekers, from motorists who drive the spectacular rim roads to kayakers and climbers. Though spectacular, it has been known beyond France for barely a century.

From among the region’s hundreds of miles of trails, we chose a section known as the Sentier Martel, in part because it requires no technical skills. Well-broken-in hiking shoes and plentiful water are the most important things to bring.

The trail, which runs from the Chalet de la Maline to the aptly named Point Sublime, showcases the gorge, an artefact of the push-pull of geologic and hydrological forces. Sentier Martel was named after the explorer who probed it for an electric utility intrigued by the hydroelectric possibilities. Although five hydro dams punctuate the course of the river and affect its flow, opponents blocked a proposal to run a transmission line across the valley. The gnarled Verdon River has carved deep undercuts in cliffs that hem it and left bars of gravel beneath others.

Hiking into a canyon, along a river and up out of a tributary valley may seem cut and dried, but the Sentier’s blazes of red and white stripes, first marked in 1928, led us through stretches of variety and occasional thrills. There were broad scree fields where rock cairns required us to cross a slope with our feet slanted. Cables bolted to the cliff offered a firm hold across an even steeper ramp of rock.

A linked set of ladders and steep steps lifted us up and over an otherwise impassable bend of the river in 252 steps. Backpackers with bulky, colourful packs bobbed up the stairs from below, puffing as they neared us at the apex.

In three segments, the trail disappears into tunnels built for an abandoned hydro project in the middle of the last century. It’s possible to navigate even the longest and dampest of them, stretching nearly a third of a mile, by groping the rock walls. But a small flashlight or even the dim light of a smartphone helps hikers safely pick a way through the puddles of seepwater and avoid careening into the walls. Several openings cut into the tunnel offer grand vistas of the roiling river.

We ambled the path along the river, pausing for snacks of dried fruit and swigs of water. We passed and repassed eclectic collections of hikers from Europe and beyond: students, groups with guides, older farts like us.

The pauses gave us time to ponder the sense of urgency we feel in our 60s, wanting to tackle physically challenging adventures while still able. We have the same inclination for adventure we had in our younger days, but our pace has slowed. We’re more inclined toward daypacking than overnight backpacking now.

The trick is to not let our minds yield to the growing constraints of age before our bodies require it.

As we exited the tunnels, we encountered hikers coming from the other direction in flip-flops and loafers without so much as a bottle of water, a sign that we must be nearing public access. Sure enough, we rounded a bend and met a parking area.

Our route continued uphill for another mile, ending at a cluster of tables with souvenirs for sale and a parking lot where a van returns hikers to their cars at the start, miles away on a winding cliff road.

We’d gotten the van driver’s card at the trailhead and fretted momentarily about where to find a phone to call him. Not to worry. A young German man and his Brazilian wife who had just finished the Sentier Martel had already called. As we waited together for the van to arrive, we learned that their birthdays bookmarked Lynda’s by a day on either side. The three sweaty, grinning hikers posed for a photo with the conquered canyon spread out behind them.

Back at our hotel in Moustiers-Sainte-Marie, Lynda soaked in the tub and popped another ibuprofen before we headed out for the healing properties of a fine dinner and the satisfaction of another day of staving off the inevitability of age.

After all, the footpath girding the coasts of Devon and Cornwall lies ahead. So does Spain’s Santiago de Compostela. —Star Tribune/MCT

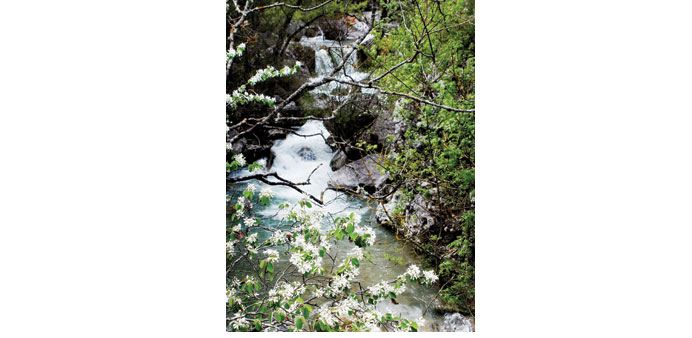

TRIBUTARIES: Rushing streams feed the Verdon River in the Verdon Gorge.