By Mary MacVean

When you buy a box of crackers labelled “natural,” do you just assume they’re organic? Don’t. When you choose an “all-natural” chocolate syrup for your kids’ ice cream, are you thinking it has less sugar? Read the label.

But what about those “natural” chips? Surely the package with the peaceful farm scene on the front means something about what’s inside — right?

There’s something about “natural” food that appeals to consumers. In one study from the consumer research firm Mintel, people were given a list of food product claims and asked which ones mattered most to them. “Natural” tied for No 1 with the claim that a product contained a full serving of fruits or vegetables.

But many of us are at a loss to define exactly what “natural” means. And, according to Michele Simon, a public health lawyer based in Northern California, that state of confusion is right where the food industry wants us.

“Natural,” it turns out, doesn’t have a definition — not from the Food and Drug Administration, which regulates most packaged food. (The US Department of Agriculture regulates meat and poultry and has its own definitions.)

“There’s a disconnect between what consumers think natural means and what manufacturers think it means,” says Nicole Negowetti, a law professor at Valparaiso University Law School in Indiana, who wrote a paper for the Brookings Institution about litigation over the word “natural” on food labels.

It’s a disconnect that has led to more than 200 lawsuits, filed by the Center for Science in the Public Interest and other groups, challenging use of the word “natural” on products that contain genetically modified ingredients or high fructose corn syrup, among other things, Negowetti says. None of the suits has been adjudicated, but some have been settled out of court.

The FDA has been under some pressure to define “natural,” and the agency has been petitioned by Consumer Reports to ban its use on food labels. The FDA has so far done neither.

But consumers might need to switch gears because those “natural” labels could be disappearing, several industry watchers say. Descriptions such as “Great Plains Multigrain” Wheat Thins and words such as “simply” and “pure” might be in line to take the place of “natural.” Pillsbury has a line of “Simply ... Cookies.” And there are “Simply Cheetos Puffs” on store shelves.

“Manufacturers are just moving on,” Negowetti says.

Companies also are making specific statements on labels, such as no GMOs (genetically modified organisms) or no artificial colours, according to Lynn Dornblaser, the director of Innovation and Insight at Mintel.

“In the bigger picture, this is the way things are going,” she says. “Companies are talking more and more about what’s in the product rather than slapping some ill-defined label on it.”

Daniel Fabricant, who left the FDA to become chief executive of the Natural Products Assn., says the landscape isn’t perfect, but shoppers should consider what’s important. The naturalness of Goldfish crackers shouldn’t be judged on the fact “that they didn’t grow on a goldfish tree,” he says, but on the fact that the dyes used are plant extracts, which is OK by him.

(Of course, consumers can use the “nutrition facts” label, governed by federal law and required to include such information as calories, amount of fat and sugar and ingredients. Still, those can be hard to interpret, in part because the listings are in grams.)

Consumers are being “duped to think certain foods are something they’re not,” says Urvashi Rangan, executive director of Consumer Reports Food Safety and Sustainability Center. She says companies should be making claims that are verifiable, such as organic, which has a legal definition.

Several companies declined to talk about their use of the word “natural”; several others did not return calls and e-mails. A representative of the Grocery Manufacturers Assn., a trade group, also wouldn’t discuss the term, saying that it tells companies to abide by FDA stipulations that the claim “natural” be truthful and not misleading.

The FDA didn’t want to talk either.

But in a statement, the agency said it “understands and appreciates that consumers depend on accurate labelling when making food choices. That’s why we have clearly defined certain terms that have public health implications, like “low-fat” or “light.” Defining “natural” represents additional challenges when food has been processed and is no longer the product of the earth.” The FDA also says it “has not objected to the use of the term if the food does not contain added colour, artificial flavours, or synthetic substances.”

And even Simon says it would be hard to advise the government on how to define the word for a food supply in which much of the soy and corn are genetically modified and many products are highly processed.

People also shouldn’t confuse natural with healthful: “Natural” potato chips might mean that the potatoes were not bleached, says Fabricant of the natural products group. “It’s still a bag of potato chips. I certainly prefer the ones that still look and feel like a potato. — Los Angeles Times/MCT

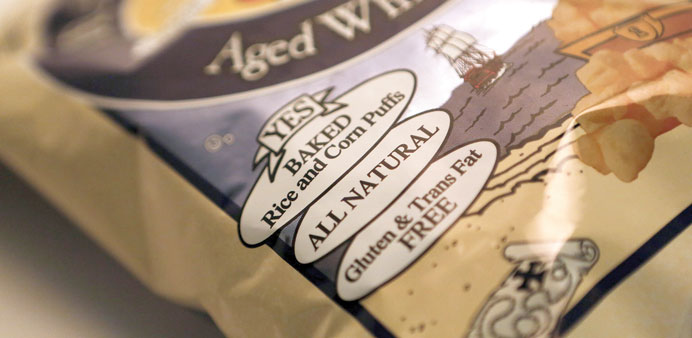

LABELLING: Pirate Booty Aged White Cheddar rice and corn puffs. There’s something about u201cnaturalu201d food that appeals to consumers.