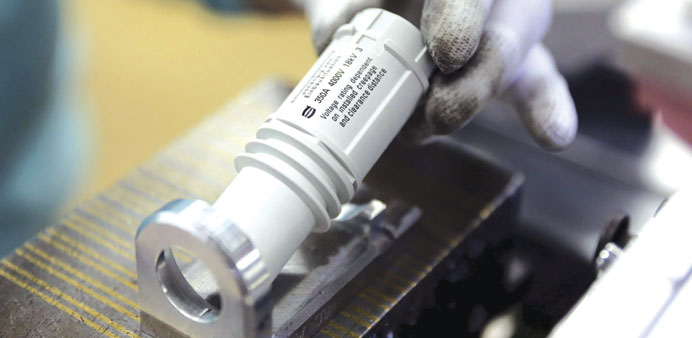

A worker of Harting, a maker of industrial plugs and sockets, removes a plug after the logo and other data were printed on it at the company’s headquarters in Espelkamp, northern Germany. Harting is one of a growing number of German firms investing in software, fearing their excellence in mechanical precision and reliability will not be enough to guarantee them success for much longer.

Reuters/Frankfurt

If customers of Germany’s Harting Group, a maker of industrial plugs and sockets, want bespoke products, they can buy them — if they’re prepared to assemble them from a kit themselves.

Volker Franke, the head of Harting’s assembly systems and machine tools business, is working hard to change that. His team is developing an automated production line that takes orders online and makes plugs to a customer’s individual specification.

Harting is one of a growing number of German firms investing in software, fearing their excellence in mechanical precision and reliability — the trademarks of “Made in Germany” valued by factory owners around the world — will not be enough to guarantee them success for much longer.

As computerised technology becomes an ever greater part of industrial processes, Internet companies are starting to eclipse low-cost Chinese manufacturers as German engineers’ main worry.

With the likes of Google investing heavily in robotics and automated driving, the fear is engineers will be relegated to selling generic hardware, while software firms make it rich with the technology that makes the machinery smart.

“Right now there are makers of factory equipment and those who buy, operate and look after it. Who guarantees that it stays that way?” asked Franke during a Reuters visit to Harting’s headquarters in Espelkamp, northwest Germany.

“It could be that somebody will squeeze their way between the two, telling the equipment user he won’t have to bother about what type of machines to use any more. This service provider will be from the digital world,” he said.

Companies that can master vast amounts of data such as Google, SAP, Amazon, EMC Corp’s cloud-computing division Pivotal and Teradata Corp could all open up the breach, industry analysts believe.

Advisory firms such as IBM and Cap Gemini and software makers such as Oracle and Microsoft could also be winners from an industrial Internet revolution, potentially to the detriment of engineers.

“Companies that provide database and analytical tools — such as IT companies or system integrators — could gather technical parameters in mechanical engineering regardless of the brand of the machine,” said Michael Ruessmann, a partner at The Boston Consulting Group with a focus on information technology.

The stakes are particularly high for Germany.

Europe’s biggest economy depends on manufacturing for a larger share of gross domestic product than any of its western European neighbours or the US, with tens of thousands of family-owned businesses — the so-called Mittelstand — the bedrock of its export-driven success.

The German government is alive to the danger.

In 2013, it launched its “Industrie 4.0” initiative, backed by the top lobby groups in engineering, electronics and high-tech, to address issues such as worker skills, data transfer standards and data security.

But so far it is larger firms leading the move to adapt, with 70% of German industry executives in a study commissioned by consultancy CSC saying they were not sufficiently informed about potential new business models.

These involve, for example, developing algorithms for how best to run a production process and packaging them into universal factory services that feed on sensor-generated data such as vibration, temperature or power consumption.

“I’m deeply concerned that there is still not enough awareness (in Germany) for the growing interconnectedness and the changes that result from it,” said Volkmar Denner, chief executive at Robert Bosch GmbH, one of the world’s largest automotive parts makers and a major player in factory equipment.

German industrial gases firm Linde, which plans to hook up oxygen tanks to the Internet so they will trigger a replacement before they run empty, said big companies could show the way.

“The auto industry and large manufacturing firms are acting as pioneers while small and medium-sized companies are rather in a discovery phase, thinking about what is feasible and what isn’t,” chief executive Wolfgang Buechele said.

Consultancies and technology firms are pitching to fill the gap in information and skills at factory equipment makers.

The advisory arm of auditor PwC reckons about half of German industrial groups’ investments in plant and equipment will be driven by “Industrie 4.0” over the next five years, equal to about €40bn ($43bn) per year.

With a strong starting position and a tradition of collaboration and communication, the Mittelstand is well placed to adapt, according to Michael Ziesemer, president of German electronic hardware makers lobby group ZVEI.

“The German industry is the equipment supplier to the factories of this world,” he said. “If we manage to stay ahead, there could be more jobs in Germany in the end.”