Bloomberg/New York

With graduation season around the corner, more than a few US families are probably wondering just how much that college degree will be worth.

There’s little doubt education is associated with higher income, better financial decision-making and more wealth.

However, issues that are harder for an individual to control — what type of family you come from, whether you get an inheritance, or how healthy you are — also play a growing role in determining your net worth, according to a new report by researchers William Emmons and Bryan Noeth at the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis.

Education “is important, but it’s not the whole story,” Emmons, a senior economic adviser at the St Louis Fed, said in an interview. “You can’t simply send everyone to college and expect to solve all the social problems that we have, including problems in the job market.”

Family background, such as your parents’ social class, occupation, education and income, also has a hand in wealth-building, Emmons and Noeth found. Wellness can play a role because people who are fit can work longer and incur fewer healthcare expenses in retirement. There is also what sociologists call “assortative mating”, or the tendency of highly educated people to marry each other.

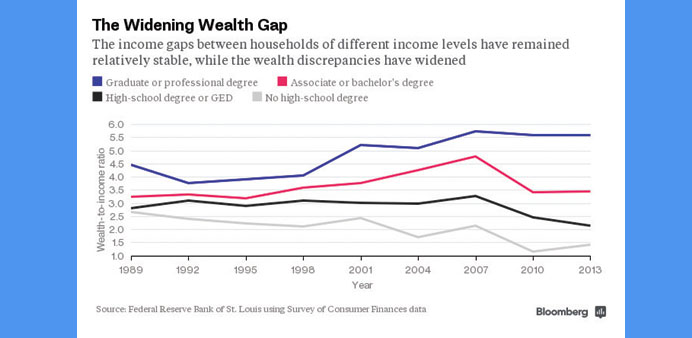

The bottom line is that these other influences help translate income into wealth. The result is a growing gap between the net worth of more-and less-educated families even as the disparity in income stays fairly constant. The following chart depicts the wealth-to-income ratios of households led by someone 40 years old or older with various amounts of education. The rate shows how easily a family can turn earnings into net worth.

“Increasing the educational attainment alone of an individual or group is unlikely to result in all of the positive effects that are hallmarks of families with advanced education,” the researchers wrote in the paper. “Some important contributors to the economic and financial success of many highly educated people cannot be granted along with a degree.”

While the US has taken strides to make going to college more accessible, the financial outcomes of those who don’t get additional schooling have deteriorated. That means if four years at a university isn’t a good fit for you, your economic picture has gotten bleaker.

The median net worth of families headed by high school graduates was $95,072 in 2013, down 36% from $149,182 in 1989 after adjusting for inflation, according to data from the Survey of Consumer Finances. By comparison, wealth levels for families with graduate or professional degrees rose 45% to $689,100 over the same period.

“More of the people who have the potential to go to college are going to college today,” Emmons said. “But the flip-side is that for those who don’t go to college, their opportunities look much less promising in this narrow financial sense.”

This made me think of my 70-year-old uncle, who lives in western North Carolina. He didn’t finish high school, but was still able to work for a railroad his entire life and generate a solid, stable income stream for his family. He bought land, built a home, helped his son through college and is now enjoying retirement. Scenarios like that are becoming increasingly rare, Emmons said, because “the job opportunities are not there.”

The odds of becoming millionaires for a family headed by someone 40 or older without a high school diploma were 1 in 110 in 2013, according to Emmons and Noeth’s calculations. That compares to 1 in 2.6 for a family headed by someone with a graduate or professional degree.

Moreover, much of the educational attainment in the US is concentrated among white and Asian households, adding a racial filter to the issue. At the graduate-and professional-degree level, only Asians have shown a strong upward trend in educational attainment, while blacks and Hispanics, who will be responsible for much of the US population growth in the coming years, still trail other races at every schooling level.

Gender differences are also at work, with women of every race and ethnicity passing their male counterparts at each education milestone, Emmons and Noeth find. This is problematic considering that women have lower labour force participation rates and have yet to reach pay parity with their male colleagues.

“The continuing barriers facing women in fully contributing to their families’ and the economy’s progress, together with the rising share of the black and Hispanic population with very low education levels, make it likely that educational advances will contribute less to economic and financial growth in the future than they have in recent decades,” Emmons and Noeth wrote.