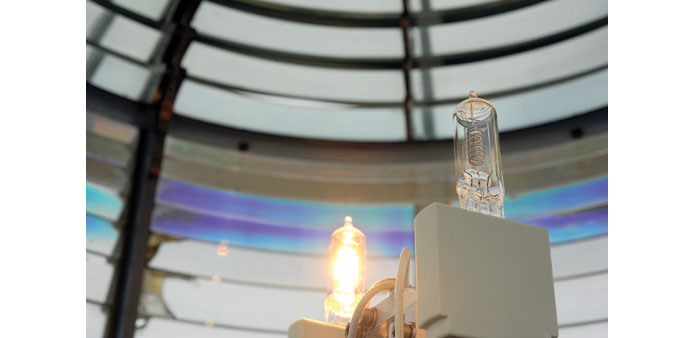

THE LAMP: Inside the lantern room of the Point Pinos Lighthous a 1,000-watt lamp is amplified by the lens to produce a 50,000-candlepower beam visible up to 17 miles under favourable conditions in Pacific Grove, California.

By Joan Morris

As thousands of seagoing adventurers, caught up in gold fever, made their way along California’s long, dark coast, not a single light led the way.

Then, in 1855, a powerful beam cut through the night, a beacon that warned of hidden rocks and dangers along the coast — and provided the only glint of gold that most of those would-be miners would ever see. For 160 years, the Point Pinos Lighthouse has stood guard on the shores of Pacific Grove and Monterey, a navigational aid for countless mariners and a magical place that is being restored and preserved by dedicated historians.

The lighthouse is something akin to a time machine. It allows visitors to travel back to the shining days of early statehood and the dark hours of World War II. And it’s a repository of fascinating stories and characters, from the first keeper, Charles Layton, who joined a posse and was killed, leaving his wife to keep the light burning, to “Socialite Lightkeeper” Emily Fish, who was principal keeper for 21 years and was known for hosting elegant lunches and dinners for naval officers, artists and writers inside the lighthouse proper.

The stories, if not the light itself, might have been lost without the dedicated crew of volunteers from The Heritage Society of Pacific Grove, which has preserved several significant buildings in that city.

Today, the sprawling coastal grounds and the lighthouse — up to the rim of its lantern room — are the property of the city of Pacific Grove. The Coast Guard owns the beacon and the room around it. And Dennis Tarmina, a Heritage Society member, came up with the idea of adopting the lighthouse as a service project one morning, while eating breakfast at a local cafe with some other society members.

“We were kind of looking for something to do,” Tarmina says.

They sold the idea to the rest of the society with the promise that they were just going to caulk some windows, maybe splash some paint around. Once inside, they discovered there was much more to do.

“There was about 150 years of built-up paint,” volunteer Steve Honegger says.

“It was leaking, and there was massive corrosion,” volunteer Ken Hinshaw says. “We found a lot of reports of what needed to be done — but none of the work had been done.”

The group has spent the past six years repairing windows, sanding floors, shoring up the lantern room, and researching the past to bring it front and centre. Most of the rooms are now decorated to reflect various eras. Using a manual prepared for them by The Lighthouse Preservation Society, they are reclaiming the lighthouse, step by step.

The core volunteer group — Tarmina, Honegger, Hinshaw, Bill Peake, Fred Sammis, Lowell Northrop, Dan Myers, lead docent Nancy McDowell and others — also are looking at ways to bring the lighthouse into the future. Among the discussions: solar power, which would make it the first lighthouse to use the energy of the sun to light the night, and interactive displays that can be activated via smartphone.

“We’re trying to come up with the best way to tell the story,” Hinshaw says.

It’s a compelling tale. The lighthouse was built from a kit, one of eight shipped from Baltimore in 1852. The ship, a 1,200-ton bark named the Oriole, contained everything the new state of California would need to construct eight lighthouses and finally illuminate the coast from San Diego to Crescent City.

The Oriole carried the windows, doors, floors and 14 craftsmen — walls and roofs would be made from local materials — around Cape Horn and into San Francisco Bay, completing a five-month journey. The plans were modelled after New England lights and included two revolutionary new ideas.

Instead of a stark tower with a long, winding staircase and the keeper’s house nearby, the lighthouse tower would be built on top of the Cape Cod-style house, allowing the keepers to tend the light without having to suffer through the elements. The lights also would be outfitted with Fresnel lenses, a French design that uses large glass prisms to focus the light beam.

The lenses had been lauded in Europe for improving the strength and quality of the light, and the United States had decided that all of its lights would be fitted with the costly yet effective lenses.

Point Pinos Lighthouse, standing back from the water’s edge on a pine-topped hill, became the second lighthouse built in California. The first, nearly a replica of Point Pinos, was built on what was then known as Bird Island and is now known as Alcatraz.

Point Pinos has a fixed light that is on for three seconds and off for one, which helps mariners identify it. It stands 43 feet tall, almost 90 feet above the water, and its brilliant 1,000-watt bulb and third-order Fresnel lens can be seen 17 miles out to sea. With the exception of World War II, when the light was turned off and the Coast Guard stationed nearby to keep watch for an invasion that, thankfully, never came, the light has never faltered, or at least not for long, making it the state’s oldest continuously operating lighthouse. — San Jose Mercury News/TNS