Reuters/New Delhi

When India releases data today that is expected to show the economy growing faster than China for a second consecutive quarter, sceptics could be forgiven for asking: Why does it feel so slow?

Celebrating his first year in office, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has basked in the success of transforming India into the fastest growing major economy.

But there are nagging doubts over whether a new way of calculating gross domestic product, introduced by the government earlier this year, has distorted the macroeconomic view.

“The economy is not as strong as the GDP numbers might suggest,” said Shilan Shah, India Economist at Capital Economics. “The numbers should not have any bearing on policies and both the central bank as well as the government should look at other activity indicators.”

The robust headline growth is hard to square with weak industrial activity, grim corporate earnings and an elusive recovery in bank credit.

The median estimate from a Reuters poll of economists put GDP growth at 7.3% in the January-March quarter, slowing from 7.5% in the previous quarter.

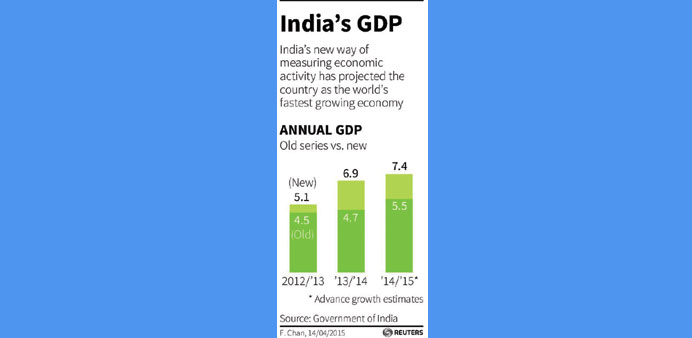

For the 2014-15 fiscal year ending in March growth is expected at 7.4%, up from 6.9% in 2013/14, using the new series.

That is a startling turnaround from the previous data series that showed the economy was still struggling to gather steam after posting two successive years of growth below 5% – the longest spell of such low growth in a quarter century.

If India was doing so well there might be far less need for the central bank to lower interest rates for a third time this year, as analysts expect it to do at a policy review on Tuesday.

But, the economy is still suffering from slack. Corporate sales and industrial production are down.

Merchandise exports have fallen for five months in a row.

Output of cement and steel, a proxy for construction, has been extremely weak. Growth in bank credit in the fiscal year ending in March was the slowest in two decades.

Arvind Subramanian, the government’s chief economic adviser, this week likened the state of the economy to flying on “one-and-a-half engines”.

“Bad stuff has stopped happening, but the good stuff is still waiting to happen,” he said.

Whereas India’s statisticians changed their calculation of GDP to come into line with global practices, it has left economists inside and outside government groping for a clear interpretation of the data.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has warned the new series is clouding the picture, and reckons growth is still slow in picking up. Still, the economy is in better shape than when Modi took the reins a year ago with the slogan “good days are coming”.

He has been helped by a dramatic slide in global crude prices that has cooled inflation and helped narrow the fiscal and current account deficits, giving the RBI leeway to cut interest rates.

Modi’s drive to make it easier to do business in India has generated optimism, and has led to a marked increase in foreign direct investment.

A massive increase in the government’s planned spending on roads, railways and ports this year is expected to break a persistent investment logjam.

Yet, businesses complain that too little has changed and are reluctant to ramp up investment, as their balance sheets are already stretched. Banks, saddled with mounting bad debt, are also cautious lenders.

“So far, not enough has been achieved to suggest that India can fulfil its economic potential over the medium term,” said Shah of Capital Economics.