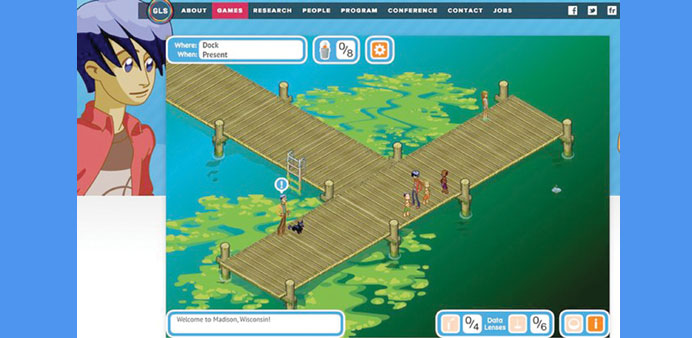

LEARNING WHILE PLAYING: In Citizen Science, a game takes place on the shores of Lake Mendota in Madison, Wisconsin, shown here polluted by algae and unsafe for swimming. Games-Learning-Society developed the game as part of its catalogue of educational games.

By Eric Hamilton

Traveling through time, talking to animals, and saving the day — they’re all video game staples.

And you’ll find all of them as you also figure out how to save Lake Mendota from pollution.

That’s the idea behind Citizen Science, a game that teaches players about lake ecosystems. It’s part of the catalogue of Games+Learning+Society (GLS), which bills itself as one of the longest standing games-for-learning research centres in the world. Working out of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, GLS is a key player in a growing field that brings together scientists, educators and game designers to augment traditional science education with games that engage students with dynamic, immersive lessons.

The innovative centre uses games to promote learning about biological systems, civic activism, empathy and literacy.

Far from replacing educators, game designers hope the games promote smarter classrooms where teachers use games to extend their lessons in new ways.

Kurt Squire grew up playing, and learning from, video games. Now, as co-director of GLS, he tries to develop games that make learning science a more active process.

“I was personally struck by the fact that we have these lakes right in downtown Madison that you can’t really swim in,” he said. That curiosity led to the development of Citizen Science.

In the game, players investigate the causes of pollution at Lake Mendota by travelling through time, collecting evidence and cleaning up the lake. Students can explore interconnected ecosystems and the long-term effects of pollution in a way that can be difficult to observe and measure during a semester, let alone a single field trip.

That’s what Robert Bohanan thinks makes video games effective for teaching science. He consulted with GLS on Citizen Science and is an outreach programme manager at UW-Madison’s Summer Science Institute, a college experience programme for high school students. He uses the game to simulate lake ecosystems and to reach more students than he can with traditional teaching materials.

“Some of the students that are the most engaged (by games) are also the students that are often the least engaged otherwise, which is really cool,” he said.

Although only a few years ago educators were less sure of the role, if any, video games could play in education, teachers are increasingly embracing them as tools to expand their curriculum. The relevant question has shifted from whether video games should be used to how they should be used in classrooms.

Mike Lawton teaches biology and chemistry at Milwaukee’s Rufus King International School-High School Campus and during the summer at UW-Madison’s college preparatory PEOPLE Program. He gave feedback to GLS on Citizen Science and uses the game in his lessons.

“Games are very intellectual. They’re going through the scientific method in a game,” he said.

Part of the shift toward educational games depends on the increasing familiarity of gaming in society, due to proliferating smartphones and tablets.

Outside the university, companies such as Madison’s Filament Games develop games for other groups and market their own series of games directly to schools. Chief executive Lee Wilson, who used to work in textbook publishing, said games can teach about dynamic systems in a way static materials cannot. Students have logged 30 million play sessions on their titles.

The field remains young, and evidence is still accumulating about the effectiveness of educational video games. Several studies hint at the possibility that these games can help students learn how to perform science, not just facts.

Everyone in the field seems to agree: This new wave of scientific video games depends on effective teachers and lesson plans to bring out the best in them.

“I really see them as being a complementary piece to what’s already going on in classrooms,” Lawton said. —Milwaukee Journal Sentinel/TNS