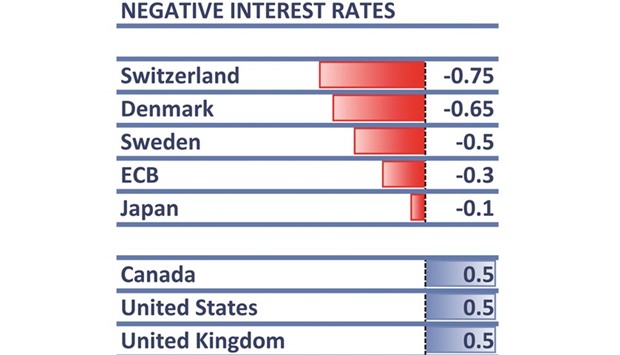

Switzerland did it; Sweden, Denmark and, as of recently, the European Central Bank and Japan, at least for larger reserves: They pushed interbank interest rates below zero, and many banks in those countries started to pass on the costs to large depositors, while the large mass of retail clients might come next to be hit by below-zero returns on their savings.

Commentators called it “bizarre” that the process of saving money at a bank now leads to a reduction of the principal as money in the form of negative interest has to be paid for the “privilege” of maintaining a deposit. But it has become a financial fact as central banks of major economies keep battling persistent systemic weakness and low inflation and try hard to spur credit growth.

The serious issue that the entire financial world, including Islamic finance, is facing is that never before in history interest rates below zero have been used in so many economies at the same time, and more countries are likely to follow – Norway, Canada, the UK - and even US Federal Reserve chairwoman Janet Yellen said that she was “open to the possibility” of introducing negative rates although she just had started raising them.

And after that happens, the era of zero or negative interest rates could extend for several more years Barclay bank said in a study released on March 3.

“Negative nominal interest rates are more than just a passing monetary fad,” said Michael Gapen, one of the bank’s top economists, adding that he believes “the era of low or even negative interest rates across the developed world could last for several years to come.”

But when negative interest rates in the UK and the US become a reality and indeed last for several years, then the Islamic finance sector will have to deal with a fundamental problem even though it doesn’t even use an interest scheme in its system. The UK’s Islamic finance sector, which just emancipated itself from a niche to a sizeable segment of the financial industry and to a Western hub for Islamic finance, would feel the heat immediately, and Gulf Cooperation Council nations, all of whose currencies but one are pegged to the US dollar and which have large Islamic finance industries, would be forced to absorb the negative interest effect in their macro economies and their banking system.

For Islamic finance, dealing with the fallout of negative interest rates from the conventional finance system on such a large scale is a first. It is subsumed in the Shariah finance theory as “unconventional risk,” disequilibrating the basically balanced risk-sharing principle of Islamic finance which, as we know, does not use interest neither for loans nor for deposits, but – in simplified terms – sets profit rates for borrowed money on the back of an asset it buys and leases to a client.

But because Islamic banking stands in open competition to conventional banking and thus always brings its profit rates in line with conventional interest rates for both deposits and loans – which is imperative to avoid arbitraging and a subsequent collapse of the financial system – it will have to rebuild the zero-to-negative interest environment.

But this is extremely difficult because Islamic banks in such a scenario would not earn profit rates on borrowings any longer, and at the same would have to charge “negative profit rates” (i.e. additional fees) for deposits which would of course incentivise depositors to withdraw their money. It would cause a liquidity crisis for the bank itself in the process, in addition to a run of clients seeking to refinance their Islamic loans and restructure their debts which they only can do by setting up sale and buy-back agreement at a cost.

Here it strikes back that most Islamic finance institutions did not catch up by developing sufficiently dimensioned hedging products or derivatives which could fend off these problems to a certain extent. Thus there is nothing much left for Islamic banks in the lending business than to use their profits from good years to cover losses from the current bad years – in the worst case stressing their balance sheets to the utmost in case Barclays’ prophecy comes true.

NEG