Meray mulk ke ghareebon ka khayal rakhna (look after the poor of my country).

Famous last words of the man Mother Teresa famously called a saint.

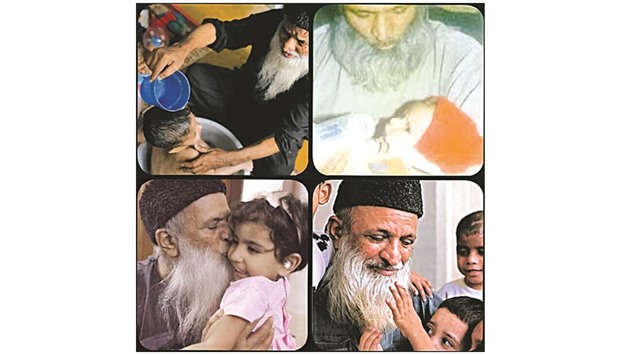

When someone has looked after the poor and the dispossessed selflessly, relentlessly, obsessively for more than six decades, words begin to fail. A bit like how daily Pakistan Today’s profound epitaph of a headline on the passing of perhaps, the greatest humanitarian in modern history suggested:

Abdul Sattar Edhi:

Too big for words

If you want to get a measure of the man - not that evidence is needed - Pakistan stood still, infectiously united in grief, on Friday when news of Edhi’s demise finally broke. One says ‘finally’, because rumours to this effect had surfaced in the recent past, more than once, given his rapidly deteriorating health. Only last month, the Foreign Office blundered in issuing a condolence message following one such call. This time, there would be no going back.

For all the inevitability surrounding death - and in Edhi’s case, a seemingly closer call given his precarious condition - the reality begins to bite when those larger-than-life shadows begin to assume sepia tones.

The sense of grief in Pakistan is palpable because in a nation often riven by fissures and hopelessness springing from a lack of governance, there has never been anyone like Edhi, the absolute last man standing where humanity, love, selflessness and trust is concerned.

But being Edhi, he wasn’t done. Not with literally, making his own grave a quarter century ago, and a will to be buried in the same clothes he last wore - all he ever kept to himself were two pairs of a tunic all his adult life and a pair of shoes worn for two decades, repaired whenever needed, and making a windowless room with a bed, sink and a hotplate his assets!

As well as making that last clarion call about his beloved poor on deathbed, Edhi donated his eyes - bequeathing any other organ was implausible as these had been rendered unproductive - corneas of which were successfully transplanted in two blind persons, hours after his death. Post-surgery, they are set to see the world for the first time in a week from now. Remarkable that A Mirror To The Blind (Edhi’s acclaimed biography) would on take a literal meaning here!

Edhi’s life in the phenomenal service of humankind - even if the Nobel Prize Committee never noticed it to the great resentment of millions, but only a shrug from Edhi himself - cannot be possibly encapsulated in one piece. But the least one can do is to make an attempt to pay one’s due. This was a man who single-handedly established a network of charitable homes, including an emergency service that provides ambulances and other assistance for the needy.

The hotline fields an emergency call, on average, every 8-10 seconds - some 10,000 in a day with 6,000 in Karachi, the world’s second most populous city, alone. Before kidneys failed him in 2013, Edhi would often pick up a call himself and be the first to arrive on the scene in that familiar white coloured, horn blaring ambulance - one of over 1,800, the world’s largest such service.

The Edhi Foundation also boasts three dozen rescue boats, two fixed-wings planes and a helicopter.

So enormous was the respect and reverence Edhi was held in that often when an ambulance arrived on the scene in response to an SOS call - smack in the middle of an ongoing shootout between notorious political gangs and the police in a Karachi cauldron - they would cease fire before resuming battle once the ambulance left!

Replete as Edhi’s life was with incidents that brought home a converted soul, he was once robbed by a gang of thieves, but just as they were about to leave, one of the them recognised Edhi and a profuse apology later, immediately returned the spoils, and himself pulled out a hundred rupee note to donate, telling astonished fellows in the gang: “We can’t do this; this is Edhi, who is the only one who will come to our rescue even when our family would have forsaken us!”.

But ambulance service is just one, albeit more visible, of the chain of charity work rendered by the Edhi Foundation. The ‘Angel of Mercy’ did more with shelters for the homeless, the sick, the physically and mentally challenged and orphans. According to 2014 figures, there were 17 shelters for women seeking refuge from domestic violence and other abuse, nursing homes, hospitals and blood banks.

His centres are abroad, too, in the US, Canada, Afghanistan, Nepal and the Middle East.

From reaching out to refugees in Afghanistan to famine victims of Ethiopia and even victims of Hurricane Katrina in the US, the Edhi Foundation has made its presence felt. The Foundation also has the largest morgue in Pakistan which can accommodate 300 bodies at a time. The free kitchen in Karachi affords meals for 30,000 people every evening.

A large animal home where abused, sick and abandoned animals are taken care of and fed is just another hallmark of the saintly Edhi’s legacy.

None in modern history however, rival his work in giving dignity to the dead. He brought back bloated, drowned bodies from the sea - black bodies that crumbled with one touch - and others from rivers, inside wells, accident sites and hospitals.

As his biography notes, when families forsook them and authorities threw them away, he picked and brought them home to his work force to give them a decent burial.

But perhaps, what outdoes everything else was his decision in the 90s to take in abandoned babies, ignoring an outcry from the clergy, which would rather brush it under the carpet than address the deep-rooted problem.

Up until 2014, partnered by his equally devoted wife Bilquis, Edhi had helped save more than 40,000 unwanted babies; feeding, nurturing and educating them. Many of them rose to be in positions of advantage in society, while still others chose to return to Edhi homes to take care of the dispossessed, in turn.

Still Edhi did not have an easy life, facing the wrath of the mullahs and political mafias in Karachi, who resented the citizenry’s deep sense of loyalty to him in giving alms and trusting him with their money which they wanted for themselves and did so by force. This never stopped Edhi from giving them two hoots, and carrying on with his mission undeterred. Not only did he shun them and any activity that smelt of pomp and ceremony, he refused to take money from the rich or foreign organisations, often turning down millions. “If the common people are the givers, it will last forever,” he used to say.

More recently, he declined an offer from former president Asif Zardari - infamous for his alleged ill-gotten wealth - to be treated abroad, gesturing with a frail hand that he was content to be home.

All this was reflected in what he said years ago about his country, people and rulers.

“Pakistanis give wholeheartedly. They give tens of thousands and they don’t even take a receipt. They just walk in and give. This is a good country. It’s just run by bad people.”

Much said. With the typical soul and simplicity of an Edhi. RIP.

The writer is Community Editor.

PHILOSOPHY: u201cWhat use is education when we do not become human beings? My school is the welfare of humanityu201d - Abdul Sattar Edhi