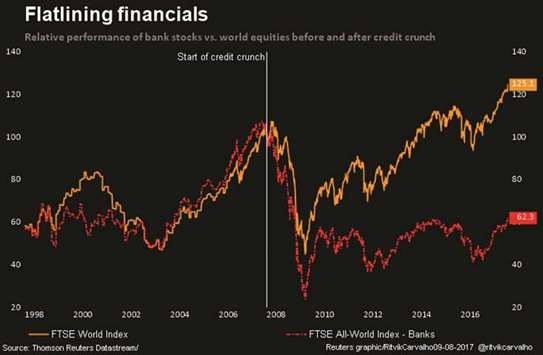

Ten years ago to the day, the European Central Bank pumped €95bn into the banking system to prevent it from seizing up, marking the start of the global credit crisis.

At the time it was the biggest ever injection of funds into financial markets and probably the most stunning single central bank action to date.

It was also the first step taken by any major authority to tackle the unfolding credit crunch.

It was a bold and decisive step which pointed to a nimble, flexible and forward-looking central bank. Yet it was also a conventional move and one that wasn’t followed up quickly enough with other measures.

Though the ECB was rightly seen as the vanguard of crisis prevention back then, it soon fell in the slipstream of other central banks — notably the Federal Reserve and Bank of England — who adopted much more aggressive and unconventional policies as the crisis unfolded.

As Steven Englander at Rafiki Capital Management notes, then-president Jean-Claude Trichet’s ECB was fulfilling its role as the traditional lender of last resort to a banking system in distress.

It used liquidity provisions to ease financial tensions. These tensions suddenly appeared on August 9, 2007, when French bank BNP Paribas shut off access to three mortgage-related funds.

It was the clearest sign to date that the financial system was malfunctioning and by common consensus was the start of the global crisis.

At the time, €95bn was an astronomical sum which many observers believed would unblock the global money markets through which trillions of dollars of interbank lending flows and upon which the world economy and financial system is built.

Yet what seemed like a prescient, intuitive action exactly a decade ago merely became part of patchier, more hesitant response over the following years of turmoil. That more muddled navigation was encapsulated best by a premature interest rate rise just months before the Lehman Brothers collapse in 2008 and also an inability to contain the early wildfires of the euro debt crisis in 2010 and 2011 — at least not until ECB President Mario Draghi’s dramatic intervention in mid-2012.

It didn’t prevent the biggest financial crisis since the 1930s, the first contraction in global output in decades, or stave off the eurozone crisis that followed and which came close to blowing up the entire single currency project.

And it proved to be a drop in the ocean of trillions of euros, dollars, pounds, yen and yuan liquidity and guarantees that central banks and governments around the world were ultimately forced to provide and are still providing.

According to one former central banker, there was little understanding in August 2007 of how seriously the incipient money market and banking problems would affect the global economy. “There was a concern that policymakers should not over react to financial market developments.”

But €95bn bought some time. It would be another seven months before US investment bank Bear Stearns collapsed, and over a year before the implosion of Lehman brought the global financial system and economy to its knees.

In some ways, it was the high point of Trichet’s ECB presidency.

He would later be heavily criticised for raising interest rates in 2008 and 2011, and not implementing quantitative easing.

Banks are the lifeblood of the eurozone economy to a larger extent than in the United States or Britain, where capital markets play a greater role in raising debt.

So €95bn of cheap cash to ease interbank lending strains was a natural step, no matter how unprecedented.

Trichet’s ECB dabbled in a range of unconventional policies to stabilise markets after that, but unlike the Fed or it didn’t implement the large-scale purchase of sovereign debt as a policy tool that could be viewed as bailing out governments.

To be fair to Trichet, he faced a much harder job getting his colleagues on board with the idea of QE.

Respective Bundesbank chiefs Axel Weber and Jurgen Stark, both staunchly anti-QE, resigned in 2011 before their terms on the ECB Governing Council were up.

Under Draghi’s presidency — mostly after the euro crisis threatened to bring the entire single currency edifice crashing down — negative interest rates have been imposed and the ECB has bought over €2tn of government and corporate bonds.

*Jamie McGeever is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are those of the author.

.