When the authorities in Kathmandu outlawed the use of vehicle horns in April, the start of the Nepali year, many expected the ban would go the way of most new year’s resolutions and be quickly forgotten.

But six months later, the streets of the capital remain remarkably quiet. In a city where a horn was widely used as a substitute for a brake, Kathmandu’s drivers appear to have kicked their noisy habit for good.

“To mark the new year we wanted to give something new to the people of Kathmandu,” said Mingmar Lama, the head of the traffic police at the time the ban was introduced. “The horn is a symbol of being uncivilised. We wanted to show the world how civilised we are in Kathmandu.”

The ban is now being introduced in other parts of the country, including the tourist hotspot Pokhara.

“We received a lot of complaints about horn pollution. Everyone felt that in recent years it had become excessive,” said Kedar Nath Sharma, the chief district officer for Kathmandu. “It was not just the view of one person or community; we all felt the same. It was

discussed in every tea shop.”

Sharma credits the success of the policy to consultation with all stakeholders, a “massive” information campaign and flexibility over implementation. “Also, there was nothing to spend and no investment needed – it was just a change in behaviour,” he added.

Surya Raj Acharya, an urban scientist based in the city, believes horn use was not a deep-rooted habit. “People pressed the horn just for the sake of it … 80% of the time it was unnecessary. It was mostly just to express their

indignation,” he said.

Drivers in Kathmandu have kicked the habit of continually using their horns after the authorities introduced a horn ban in April 2017.

Drivers in Kathmandu have kicked the habit of continually using their horns after the authorities introduced a horn ban in April 2017.

The horn ban follows other successful initiatives to improve drivers’ behaviour, including a crackdown on drink-driving and enforcement of lane discipline. “The public really trust us. If you are known by people as being honest they will follow your reforms. They will be convinced it is for the common good,” said Sarbendra Khanal, the current head of Kathmandu’s traffic police.

But civic pride has its limits. Law enforcers have issued almost 11,000 fines for horn use since the ban was introduced. At Rs500 ($5.5), a fine is roughly a third of what a taxi driver earns in a day, leaving drivers such as Krishna Gopal Maharjan fuming. “We have dogs, cows and tractors crossing the streets, so we need our horns,” he said.

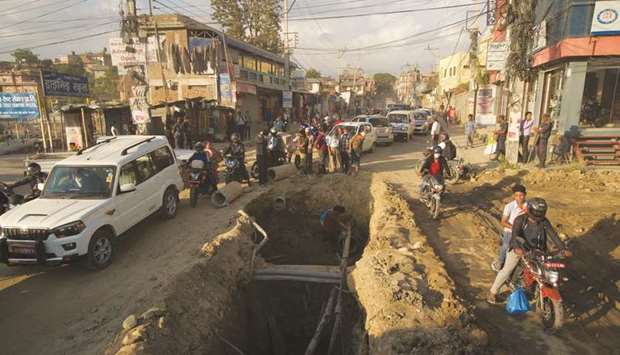

Kathmandu’s streets may now be quiet, but in every other way they remain congested, chaotic and polluted. Roads are dug up, resurfaced and then dug up again; buses and trucks emit black fumes while traffic police, caked in dust, try to keep order in a city without a single traffic light.

In an effort to cut pollution, the government banned vehicles over 20 years old, but unlike the horn ban the policy has been aggressively resisted. “The syndicates that run passenger vehicles are very strong, so the government has failed to phase them out,” said Meghraj Poudyal, vice president of the Nepal Automobile Sports Association. “People earn money from them, so the syndicates are bargaining with the government. They will only give up the [old] vehicles if the government pays them.”

Similarly, the traffic police have largely relaxed an initiative to curb jaywalking. Immediately after its introduction, thousands of pedestrians were fined every day, but many were unable or even unwilling to pay, citing the shortage of zebra crossings.

Acharya is not convinced by the approach. “When the economy is developing and people are poor, it will not work if you put a financial burden on people.”

Kathmandu’s drivers must contend with chaotic roadworks.