The landmark elections for national and provincial parliaments capped Nepal’s 11-year transition from monarchy to federal democracy after a brutal civil war.

Many hope they will usher in a much-needed period of stability in the impoverished country, which has cycled through 10 prime ministers since 2006.

An alliance of the main Communist party and the country’s former Maoist rebels is expected to form the next government, ousting the ruling centrist Nepali Congress.

“If Nepali Congress had done good work, it would not be wiped out like this from the country. The people are giving these parties a chance but if they do nothing for the country, they will also be wiped out,” said one voter, 66-year-old farmer Lachu Prasad Bohara.

The Himalayan Times said the leftist alliance’s strong mandate meant the country “could experience political stability”, which it has lacked over the last decade, but cautioned that a strong opposition was also crucial in the young

democracy.

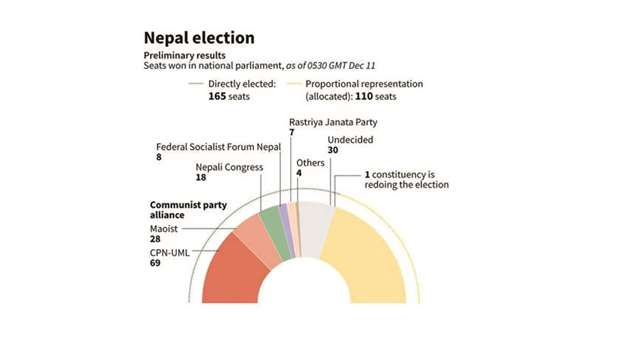

With counting still going on, the alliance has won 105 seats in the national parliament, according to preliminary data from the election commission. The incumbent Nepali

Congress has won just 21.

That puts the alliance on course for a hefty majority in the country’s 275-seat parliament.

The assembly is made up of 165 directly-elected seats, while the rest are allocated on a proportional representation basis, guaranteeing seats for women, people from indigenous communities and the

lowest Dalit caste.

The Communist bloc is also leading in six out of seven provincial assemblies mandated in a new national constitution.

The charter was finally agreed by parliament in 2015 in a rare moment of cross-party consensus, months after the country was devastated by a powerful earthquake. It laid the ground for a sweeping overhaul of the political system to devolve power from the centre to newly-created provinces.

It was intended to build on the promise of a more inclusive society, integral to the 2006 peace deal that ended the decade-long civil war between Maoists and the state.

But the constitution sparked deadly protests among ethnic minorities who said the provincial boundaries it laid out had been gerrymandered to limit their voice.

The leftist alliance campaigned on a promise to bring economic growth to Nepal.

“We will take the country towards peace and stability and move forward on the road of prosperity,” Communist Party of Nepal (CPN-UML) leader K P Sharma Oli said in a television interview late Sunday.

Oli is expected to be elected as the next prime minister when parliament sits for the first time, likely in early January.

Maoist leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal, a two-time former prime minister who led the rebel faction during the war, is also tipped for a prominent

position in the next cabinet.

During Oli’s last term in office, relations between Kathmandu and New Delhi reached a nadir after protests over the new constitution led to a blockade of the border with India and a crippling shortage of goods in landlocked, import-dependent Nepal.

The Communist leader blamed the blockade on India, stoked nationalistic sentiment and aggressively courted China for much-needed infrastructure development – undermining New Delhi’s influence over its small northern neighbour.

Analyst Prateek Pradhan warned that Oli needed to take a more pragmatic approach to balancing relations with both regional powers if he is to deliver on his campaign promise of growth.

“Nepal has to have good relations with India and that doesn’t mean you have to compromise on sovereignty,”

Pradhan said.

The newly-elected provincial assemblies will be tasked with naming their provinces, which are currently referred to by a number, choosing capitals and negotiating budgets with Kathmandu – all issues that could rekindle ethnic unrest.

But the protest movements have lost momentum as voters have become fed up with the political merry-go-round that has starved the country of much-needed development.

Most voters voiced a desire for stability and a longer-

lasting government.

The new constitution lays out strict rules for ousting a prime minister.