Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India has moved to quickly scale up its use of renewable power.

In 2014, the year Modi took office, India had 3 gigawatts of solar power.

By

the end of 2017, it had nearly 7 times that, or 20GW, according to

industry tracker Bridge to India, a renewable energy consultancy.

Now

India wants to quintuple that total by 2022 — a goal once seen as

hugely ambitious but now considered within reach by energy experts.

Progress is clearly happening quickly: During 2017 alone, India doubled its installed solar capacity from 10GW to 20GW.

“India is going to maintain and accelerate the momentum.

It

will move to be the number two player in the next year or two,” said

Tim Buckley, director of energy finance studies at the Australia-based

Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), a think

tank.

In 2017, India added the third largest amount of national solar

capacity, just behind the US and China, and was overtaking Japan,

according to IEEFA research.

Now, in partnership with France, India

wants to take its growing resources and knowledge on solar power and use

it to help other sunny countries jumpstart their solar ambitions as

well.

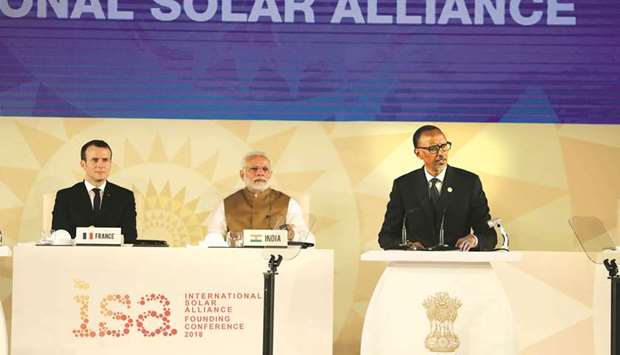

On Sunday, in New Delhi, Modi and the French President Emmanuel

Macron hosted the launch of a solar energy partnership that aims to

build a network to help tropical countries around the world boost their

use of solar power.

“In the Vedas (ancient Hindu texts), the sun was thought to be the world’s soul.

In

India, the sun was thought of as the nurturer of all life,” Modi said

at the launch of the International Solar Alliance (ISA).

“These days, when we are looking for a way to combat climate change, we must look to this ancient perspective,” he said.

As

part of the alliance, India will offer financial support to help with

27 solar projects in other countries, the prime minister said.

Macron said France also will commit 700mn euros to the alliance.

Upendra Tripathy, the director general of the new alliance, said it aims scale-up solar power in many more countries.

“Everyone

has access to (the sun) but in terms of ability to exploit solar

energy, (that) is not equal,” he said in a telephone interview with the

Thomson Reuters Foundation.

“Credit is a challenge. Skillset is a

challenge. The fundamental issue is, do all member countries have equal

ability to exploit solar energy?”

ISA plans to address that issue in

part by creating a larger, global market for solar technology that would

benefit smaller countries by aggregating the risk and the demand,

Tripathy said.

The alliance, an effort to advance the 2015 Paris climate agreement, aims to become a network of 121 countries, he said.

Currently 32 countries are full members and another 61 are on their way to full membership.

Many are developing nations.

India’s solar push is in part boosted by steadily dropping costs of providing solar energy.

To

produce a unit of solar power now costs Rs2.5 — a cost similar to that

of more traditional energy sources, said Kanika Chawla, the senior

programme lead at the Delhi-based Council on Energy, Environment and

Water, a partner organisation of the ISA.

India’s transition to

renewable energy — without shutting down its coal-fired power plants —

represents a new model for developing countries going forward, Chawla

said in a telephone interview.

But India still gets about

three-quarters of its power from coal, although that is expected to fall

to below 50% by 2040, according to the International Energy Agency.

India’s

power providers, largely state-run public companies, are heavily in

debt and as a result many companies generating solar power are not being

paid on time, Chawla said.

India’s government also is considering a

70% tariff on solar imports to protect India’s solar manufacturers —

something that is causing a lot of uncertainty as investors try to bring

new solar projects into the country, Buckley said.

Other issues for

the nation’s solar scale-up include the tricky business of figuring out

how to integrate renewables into the existing electricity grid and the

lack of a business model for such utilities — a problem other countries

using solar energy also face, Chawla said.

All of these issues have

contributed to a slowdown in the pace at which solar projects are being

commissioned in India, she said.

But what the renewable energy future holds for the South Asian giant will be critical for the world, climate change experts say.

As China’s economic growth slows, India’s is heating up, along with its energy demand.

India is today the top contributor to growth in energy demand, according to the International Energy Agency.

“It’s

worth acknowledging the Indian market and economy is still

significantly smaller than China and it will be for some time to come,”

Buckley said.

However, “India is very much wedded to the energy

transformation. It’s coming straight from the Prime Minister, and the

energy minister and the coal minister are very much onboard,” he said.

And

“especially with the US leaving the Paris agreement, there’s a

perceived void that some country needs to fill — and the International

Solar Alliance is a clever way of signalling climate leadership”, Chawla

said. “It is India’s offering to the world.” — Thomson Reuters

Foundation

Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame delivers his speech next to French President Emmanuel Macron and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during the founding conference of the International Solar Alliance in New Delhi on March 11, 2018. The International Solar Alliance (ISA) organises more than 121 u201csunshineu201d countries that are situated or have territory between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, with the aim of boosting solar energy output in an effort to reduce global dependence on fossil fuels.