Pollution is one of the great existential challenges of the 21st century. It threatens the stability of ecosystems, undermines economic development, and compromises the health of billions of people. Yet it is often overlooked, whether in countries’ growth strategies or in foreign-aid budgets, like those of the European Commission and the US Agency for International Development. As a result, the threat continues to grow.

The first step toward mobilising the resources, leadership, and civic engagement needed to minimise the pollution threat is to raise awareness of its true scale. That is why we formed the Lancet Commission on pollution and health: to marshal comprehensive data on pollution’s health effects, estimate its economic costs, pinpoint its links to poverty, and propose concrete approaches to addressing it.

Last October, we published a report that does just that. We found that pollution is responsible for 9mn deaths per year, or 16% of all deaths globally. That is three times more than Aids, tuberculosis, and malaria combined, and 15 times more than all wars, terrorism, and other forms of violence. In the most severely affected countries, pollution is responsible for more than one in four deaths.

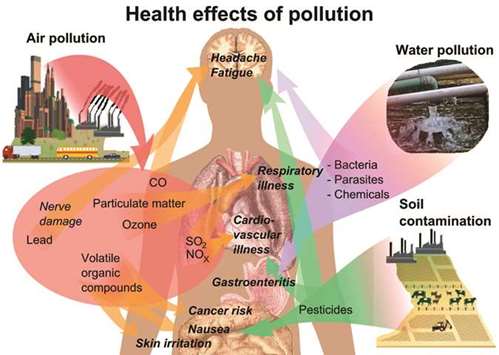

The specific causes of such deaths vary, reflecting the changing composition of pollution. As countries develop, household air and water pollution – ancient forms of pollution linked to severe poverty – decline. But phenomena associated with economic development – namely, urbanisation, globalisation, and the proliferation of toxic chemicals and petroleum-powered vehicles – cause ambient air, chemical, occupational, and soil pollution to rise, with cities in developing countries hit particularly hard.

Unsurprisingly, the poor bear the brunt of the burden. Nearly 92% of pollution-related deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. In countries at every income level, disease caused by pollution is most prevalent among minorities, members of marginalised groups, and those who are otherwise vulnerable. This is environmental injustice on a global scale.

Beyond the human costs, pollution-related diseases cause productivity losses that reduce developing countries’ GDP by up to 2% per year. They account for 1.7% of healthcare spending in high-income countries, and up to 7% in low- and middle-income countries. Welfare losses due to pollution amount to $4.6tn per year – 6.2% of global economic output. And that does not take into account the massive costs of climate change, to which the combustion of highly polluting fossil fuels is the leading contributor.

Despite these losses, the problem is set to worsen. Without aggressive intervention, deaths from ambient air pollution alone could increase 50% by 2050. Chemical pollution is another growing challenge, with an estimated 140,000 new compounds having been invented since 1950, far too few of which have been tested for safety or toxicity. Infants and young children are especially vulnerable.

Pollution is not some “necessary evil” that inevitably accompanies economic development. With leadership, resources, and a well-formulated data-driven approach, pollution can be minimised, and viable strategies have already been developed, field-tested, and proven effective in high- and middle-income countries.

These strategies balance legal, policy, and technological solutions. For example, following the “polluter pays” principle, they include the elimination of tax breaks and subsidies for polluting industries. Moreover, such strategies adhere to clear targets and timetables, against which they are continuously evaluated, and are subject to strong enforcement. And they can be exported to cities and countries at every income level around the world.

Careful planning and well-resourced application of pollution-control strategies can enable developing countries to avoid the worst kinds of human and ecological disasters that have accompanied economic growth in the past. The old assumption that poor countries must endure a phase of pollution and disease on the path to prosperity can finally be put to rest.

For rich and poor countries alike, such strategies would lead to more sustainable GDP growth. The removal of lead from gasoline has returned billions of dollars to economies around the world, as reduced exposure implies lower cognitive impairment and higher productivity. In the United States, air-quality improvements have yielded $30 for every dollar invested, for an aggregate return of $1.5tn on a $65bn investment since 1970.

Reducing pollution thus creates enormous opportunities to boost economic growth, while – more importantly – protecting the lives and health of people worldwide. The Lancet Commission calls on national and municipal governments, international donors, major foundations, civil-society groups, and health professionals to make pollution control a much higher priority than it is now.

This demands a substantial increase in the funding allocated to pollution prevention in low- and middle-income countries, both from national budgets and donor aid. This can be achieved on the international level by expanding existing programs or establishing new stand-alone funds, analogous to the Global Fund to Fight AIids, Tuberculosis, and Malaria. Such programmes should kick-start and complement national contributions, while providing technical assistance and supporting research. International funding can also be used to back the creation of a “global pollution observatory.”

Effective pollution control also means embedding strategies for prevention in all future growth and development strategies, recognising that success is possible only if societies change their patterns of production, consumption, and transportation. Key steps here include creating incentives for a broad transition to non-polluting sources of energy; ending subsidies and tax breaks for polluters; rewarding recycling, re-use, and repair; replacing hazardous materials with safer substitutes; and encouraging both public and active transportation.

The transition to less polluting systems will not be easy, and will meet fierce opposition worldwide from vested interests. But, as the Lancet Commission report shows, the low-pollution transition is essential to the health, well-being, and prosperity of our societies. We cannot afford to neglect this global menace any longer. - Project Syndicate

* Philip J Landrigan is Dean for Global Health at the Arnhold Global Health Institute and Professor of Environmental Medicine and Pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. Richard Fuller is President of Pure Earth.