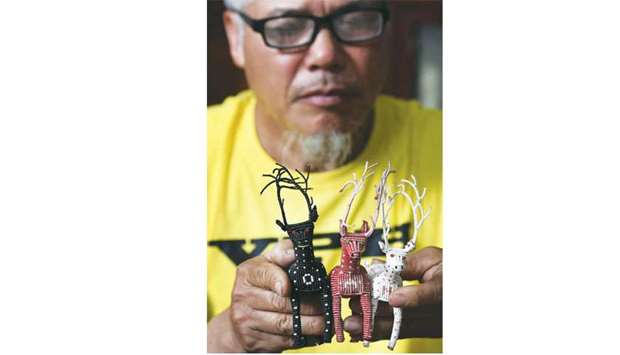

Nguyen Truong Chinh proudly holds up intricately crafted animals, flowers and hearts – secret gifts made from plastic bags by a son on Vietnam’s death row.

The palm-sized creations that his son and other inmates have furtively made and smuggled out of their solitary cells offer a rare glimpse of prison life in Vietnam.

They’re also an emotional lifeline for desperate parents fighting to free the children they say have been wrongly

convicted.

“Any time we receive the gifts from my son I feel like he’s here with me, like he’s come back home,” Chinh said, clenching his jaw to hold back tears.

His 35-year-old son Nguyen Van Chuong, convicted of murdering a police officer a decade ago, is one of a handful of prisoners known to have made the artwork that is officially banned on death row.

The families suspect they made the pieces with discarded plastic bags passed on by fellow prisoners, shredded and

woven into figurines.

They were once smuggled out by prisoners released after serving their terms but relatives stopped receiving them a few years ago, leading Chinh and other parents to fear guards have cracked down on the forbidden prison pastime.

They’re too scared to ask about the practice during brief monthly visits

closely monitored by prison staff.

But Chinh says the art still drives his decade-long fight to free his son, who he insists was nowhere near the scene of the crime he was convicted of.

“When I see the animals, I know somehow that my son is stable enough to create these things, that he is mentally strong,” said Chinh, sitting with a bag full of

documents on his son’s case.

“They motivate our fight for justice.”

Little is known about Vietnam’s prison system, but in a rare report last year the ministry of public security said 429 people were executed between August 2013 and June 2016.

That is an average of 147 per year – putting Vietnam among the world’s top executioners along with China and Iran.

The law requires death row inmates to be held in solitary confinement and

monitored around the clock.

Prisoners deemed “dangerous” have one foot shackled for most of the day, released only for 15 minutes to bathe inside their cell, where they also eat and use

the toilet.

“In many cases, acts of torture, coupled with the denial of medical care, have resulted in deaths in custody that are almost never investigated by the authorities,” Andrea Giorgetta from International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) said.

The MPS report said 36 death row inmates died behind bars between 2011 and 2016, without saying how.

In letters to his family, Chuong said he was tortured in custody: hung upside down and naked with a dirty sock in his mouth and beaten during interrogation.

Police electrocuted his genitals and prodded him with needles until he

confessed under duress, he wrote.

Vietnam’s foreign ministry rejected allegations of torture as “false information” in a statement to AFP and said it does not do anything to harm the “honour and

dignity” of inmates.

Relatives of the death row artists say their work offers a necessary diversion from constant fear of execution.

Prisoners are given little notice before their execution, which since 2010 has been carried out by lethal injection.

Before then, inmates were awakened before dawn, given a final meal and a cigarette, tied to a post and shot by five officers, with one final “humane shot” to the head, according to a 2016 report by the Vietnam Committee on

Human Rights.

Today locally manufactured drugs are used to kill prisoners, though advocates complained of inhumane deaths after a man reportedly took two hours to

die in 2011.

It’s an unimaginable end for the families who refuse to give up hope their sons will one day be freed.

Nguyen Thi Loan has sent more than 1,500 letters to the government proclaiming the innocence of her son Ho Duy Hai, 32, and gave up her land, home and job as a vendor to fight for his release.

“I’m determined to seek justice and fairness for Ho Duy Hai until my last breath,” she said of her son who was jailed over the murder of two

women in 2008.

His scheduled execution was called off at the 11th hour in 2014 by the president, raising hopes his case could be reopened.

In his earlier years in prison, Hai sent shrimp, fish and miniature horses as gifts to his lawyers, former teachers and relatives.

But she hasn’t received one in years and fears jailers have banned the practice.

“Making those gifts didn’t harm anyone. Why won’t they let my son do it?” she told AFP in tears.

Supporters hope to raise awareness about Hai’s case through his artwork, which was put on display alongside Chuong’s pieces earlier this year at an underground show by activist artist Thinh Nguyen.

He started collecting the pieces from families years ago after he met them outside government offices calling for their sons’ release.

“When I put these animals on show, their stories are known,” Thinh said. “I look at these and I see a lot of hope.”

Nguyen Truong Chinh displaying intricately crafted animals made from plastic bags by his son and death row inmate Nguyen Van Chuong, during an interview with AFP at his home in Hanoi.