Cecil Beaton laboured for much of his life under the terror that he might be considered ordinary. Yet ordinary was the last word anyone would think to apply.

Gifted and successful as a photographer, writer and artist as well as a set and costume designer, Beaton, if anything, as he himself put it, “wandered in the labyrinth of choice.”

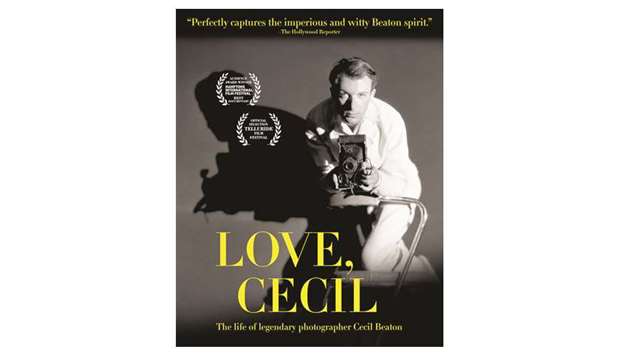

Asked by an interviewer, “Which is your main profession?” at the start of Lisa Immordino Vreeland’s empathetic, involving Love, Cecil,” the subject responds with practiced affability. “I wish I knew,” he says. “That’s been my problem for a very long time.”

There was a point in time when Beaton, who published 38 books, won four Tonys and three Oscars and was knighted into the bargain, was a ubiquitous presence on the English language cultural scene.

But 38 years after his death, Beaton’s name is not so much on everyone’s lips, and one of the pleasures of this film is to revisit his gifts beyond his best known work, the Oscar-winning production design and costumes for My Fair Lady.

Vreeland’s previous documentaries also dealt with artistic figures, including Peggy Guggenheim and Diana Vreeland, her husband’s grandmother, so she is well positioned to take Beaton on.

And her subject certainly helped his cause by writing 150 volumes of candid, perceptive diaries, excerpts from which are superbly read by Rupert Everett.

The son of unapologetically middle class parents — his father was a timber merchant — Beaton always yearned for the stature and status of upper class life.

Theatre-struck as a boy as well as intensely ambitious, Beaton was determined to be a star performer on a stage of his own creation.

A self-described “rabid aesthete,” Beaton taught himself photography, using his sisters as models, because that was an art, unlike theatre or film, “I could do without being invited.”

The tireless, hell-bent quest for beauty became what Beaton’s life was all about. As he himself put it with certain weariness, “I exposed thousands of rolls of film and wrote hundreds of thousands of words, all in a futile attempt to preserve the fleeting moment.”

But that idealistic quest didn’t mean Beaton couldn’t be waspish about other people, or, for that matter, they about him.

Jean Cocteau famously called Beaton “Malice in Wonderland” and both Truman Capote and George Cukor, who directed that 1964 My Fair Lady, are featured in vintage footage making dismissive comments.

As for Beaton himself, he was hostile toward Noel Coward and Evelyn Waugh, since childhood, despised Elizabeth Taylor for her vulgarity and said of her husband Richard Burton that he was “as butch and coarse as only a Welshman could be.”

In the face of all this vitriol, it is a tribute to Beaton’s gifts, and Vreeland’s persuasiveness as a documentarian, that we end up caring about and appreciating her subject.

Beaton first came to public notice as a photographer of the artistically daring British socialites between the wars known collectively as “the Bright Young Things.”

Beaton took himself to New York, where his photographs and his illustrations caught on at Vogue, and then went to Hollywood, where he made exceptional portraits of movie stars that captured, the film explains, the idea of the person photographed, not the person per se.

Though his gifts were obvious, Beaton also had a penchant for sabotaging himself, and he blunted his upward trajectory by printing in Vogue, for reasons no one can adequately explain, illustrations with an anti-Semitic slur embedded in them.

It took years, but two things brought Beaton back from ignominy.

One was the hard and dangerous work he put into patriotic projects during World War II, and the other was the bond he formed with a big chunk of the British royal family, including Queen Elizabeth II and some two dozen of her relatives.

Beaton managed to keep his currency as new kinds of culture came in, and Love, Cecil features new interviews with fellow British artists David Bailey and David Hockney about what interacting with him was like.

Beaton famously had a connection with Greta Garbo that might have been romantic. For years, she resisted his desire to take her picture, but when she needed a passport photo, the actress relented. Beaton considered her the most beautiful woman he ever photographed, and coming from him that said a lot. – Los Angeles Times/TNS

.