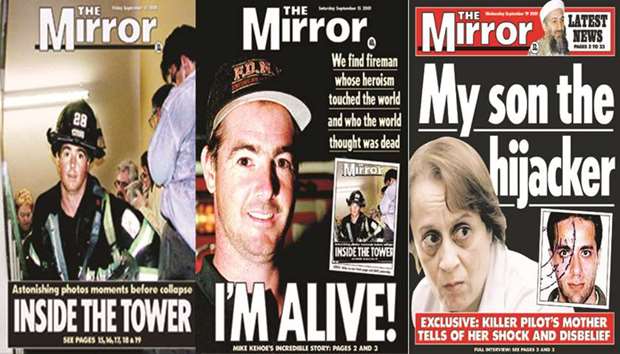

You can see the fear in the fireman’s eyes as he climbed the stairs in the North Tower, while everyone else was coming down.

When the picture of Mike Kehoe, wide-eyed and frightened, came into the office nobody knew who he was.

We didn’t know whether he was killed when the tower collapsed – as happened to so many brave firemen on that day as they tried to rescue the trapped – or if he got out alive.

Later, Andy Lines, our US editor, managed to trace him from the number on his helmet to his fire station on Staten Island. Arriving there with the photograph he gently asked if the fireman had survived.

“Sure, Mike’s asleep upstairs”, he was told.

Andy went upstairs and found Kehoe lying on the floor. “I just did my job,” he said.

Seventeen years on, my memories of the days and weeks that followed the September 11 attacks are hazy, but some things stand out as if they were yesterday. The look on President George W Bush’s face as news of the attacks is whispered in his ear as he sat with a group of children on a visit to a school in Florida.

The same man, a few days later, standing in the rubble of the Twin Towers – named ‘Ground Zero’ - surrounded by burly firemen, promising to hunt the terrorists down and “smoke’em out” of their caves in the Afghan mountains, as if he was in some cowboy movie.

I remember getting our reporter, Alexandra Williams, out of Israel so she could travel to Lebanon to track down one of the terrorist’s families.

It was to be the first interview with any of the families of the 19 hijackers and we published it just eight days after the atrocities took place.

Ziad Jarrah had the been at the controls of United Airlines Flight 93 when, it is claimed, Todd Beamer and his fellow passengers heroically stormed the cockpit trying to wrest back control of the plane causing it to crash into a field in Pennsylvania, rather than continue to its intended target in Washington.

His parents told Alex of their shock at what their son had done when she spoke to them at their home in the village of Almarj in the Bekaa Valley.

“I did not bring up my son to hate,” said his mother, Nafisa. “He was a good, kind young man, not an evil killer.”

After the interview the family offered Alex a cup of coffee and she caught sight of Nafisa going outside to draw water from the well to make the brew.

By the time Alex called me she was already being violently sick, she presumed from the water used in her coffee, and would be laid up ill in bed for days.

Our team of reporters joined US editor Andy Lines in New York three days after the attacks, flying to Canada as America had closed its own airspace and then driving through the night.

Incredible stories were already emerging. How some firemen were killed by people falling on top of them, forced to jump to escape the heat.

One was the fire brigade’s padre, Mychal Judge, who had gone into the building to perform the Last Rites to his dying colleagues. The priest died of blunt trauma to the head as the tower collapsed, screaming “God, please make this end!” as he was hit.

The picture of his body, slumped in a chair, being carried out of the rubble by his colleagues, went around the world.

As the days and weeks went by, funerals took place and many stories of bravery and heroism emerged. There were so many victims we had to start a file on each person so that reporters could see what had been already been done when they started their shift.

Before long the politics was taking over as America sought to build an international coalition to go after Al Qaeda.

From the outset the British prime minister Tony Blair was four-square behind president Bush, addressing Congress soon after 9/11 to talk about the “special relationship” between the two countries built up since the days of Churchill and Roosevelt during World War Two.

Not only was Blair prepared to join America in toppling the Taliban with an huge aerial bombardment of Afghanistan, which had been granting the 9/11 mastermind, Osama bin Laden and his Al Qaeda terrorist group sanctuary to plot their attacks.

But the prime minister also later supported a US invasion of Iraq to overthrow Saddam Hussain, which was a lot more controversial and for which he was later blamed by the British people.

There was no evidence that the Iraqi dictator had anything to do with the September 11 attacks. He was not an ally of Bin Laden.

But in 2002 president Bush had drawn up an ‘Axis of Evil’ list of countries which America said either supported terrorism or sought weapons of mass destruction (WMDs).

Blair argued that thousands had been killed on 9/11 by planes being flown into towers. But he said next time the numbers could be in the tens of thousands if terrorists were able to get their hands on WMDs.

A ‘War on Terror’ was launched that, as well as driving Bin Laden and Al Qaeda from Afghanistan, involved toppling the Saddam Hussein regime which had ruled Iraq for nearly 25 years.

Saddam had been playing “cat and mouse” with UN weapons inspectors for years and the Bush administration, driven by hawkish right-wingers such as vice-president Dick Cheney and Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, decided to remove him.

In order to convince the British parliament to support an American-led invasion of Iraq, Blair’s government on September 24, 2002 published what was later known as the “dodgy dossier”.

This famously claimed Saddam possessed chemical weapons which could be ready within 45 minutes of an order to use them.

The right-wing newspaper, The Sun, ran a headline: ‘Brits 45 mins from doom’.

At the Daily Mirror we were a lot more sceptical and the editor, Piers Morgan, campaigned long and hard against an invasion saying there was no proof Saddam had WMDs, for which he was ultimately proved right.

This stance cost us a lot of readers – at one point we lost 80,000 in five weeks – because many people who bought the paper had children or friends serving in the armed forces. By attacking the invasion of Iraq in March 2003 it was very difficult not to be seen to be criticising the troops who were putting their lives on the line.

Like the rest of the British press, we had our reporters and photographers embedded with British forces and our defence correspondent came ashore with the Royal Marines when they landed at Umm Qasr.

The Mirror was proved right when, after Saddam was toppled just over a month later, it was discovered that there were indeed no WMDs in Iraq. It had all been a trick Saddam was playing on the West.

The battle may have been won but the war was far from over. The US and Britain had not planned well enough for how Iraq would be ruled after Saddam had gone and even allowed much of the Iraqi army to disband.

What started with pockets of resistance soon became a bloody insurgency that would last for years, with suicide bombings and guerrilla warfare costing hundreds of thousands of lives, not just of the troops but the Iraqi people as well.

A study later estimated that half a million people were killed in Iraq between 2003 and 2011.

The anarchy which prevailed in parts of the country when foreign troops departed led to the rise of a new terrorist organisation, Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).

In June 2014, it captured Mosul, Iraq’s second city, marking the start of a new era of terror as the group, later known as Islamic State or ISIS, extended its bloody and barbaric rule across the border into Syria and its headquarters at Raqqa.

At one point it controlled a third of Iraq and a quarter of Syria.

The price of defeating ISIS was high: one-in-five coalition air strikes on Islamic State targets in Iraq in 2014 resulted in civilian deaths.

By waging war on terrorists, Bush and Blair began something which many claim has made the world a much more dangerous place, with the deaths of hundreds of thousands of innocents making it easy for extremists to radicalise young minds.

The ‘War on Terror’ did not end when Osama bin Laden was hunted down and killed by the Americans in May 2011.

It did not end when Islamic State was removed from Mosul and Raqqa.

It can still be seen every time the authorities react to a terrorist attack on the streets of Paris, London or New York when so-called “lone wolves” launch their attacks.

Just as Ziad Jarrah was turned from a “good, kind man” into an “evil killer”, so too are susceptible law abiding citizens still being radicalised into becoming murderous terrorists.

As my sister said to me the night of the 9/11 attacks: “The world will never be the same again.”

* Anthony Harwood is a former Head of News at the Daily Mirror and Foreign Editor at the Daily Mail.

Front pages of the Mirror on the days following the September 11 World Trade Center attack