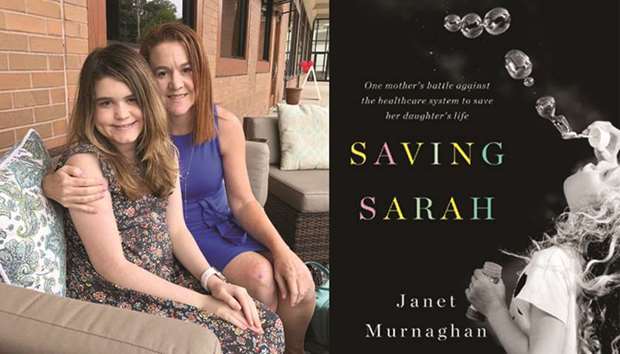

book, Saving Sarah: One Mother’s Battle Against The Healthcare System

To Save Her Daughter’s Life

'I think I see the world in a different way than most teenagers do'

— Sarah Murnaghan, survivor

It has been a little more than five years since Sarah Murnaghan left Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia with a new set of lungs, harvested from an adult donor and trimmed down to fit a 10-year-old with cystic fibrosis.

Five years since her parents helped save her life by challenging a national organ allocation system that effectively denied such adult-to-child donations.

Five years since Sarah survived a harrowing array of complications that could have left her brain damaged.

Five years that she has defied research showing people like her hardly ever survive that long. Now, she is a confident 16-year-old who contributed to her mother Janet’s just-published book, Saving Sarah: One Mother’s Battle Against The Healthcare System To Save Her Daughter’s Life. The family has moved to Florida, but Sarah and Janet were back in Newtown Square in Pennsylvania recently to promote the book.

A ninth-grade honours student who creates anime fiction, Sarah manages the ongoing challenges of immune-suppressing drugs and cystic fibrosis with aplomb. At a restaurant, she casually pulled a vial of digestive enzyme capsules out of her purse — pills she needs because the sticky mucus of cystic fibrosis interferes with digestion — and put it next to her plate of fried chicken tenders. Small for her age due to her health issues, she speaks with gravity that belies her appearance.

Surviving and recovering “made me more mature than other people my age,” she said. “Most teenagers nowadays, like, sometimes they do things that are kind of stupid. A lot of kids are vaping and stuff like that. I think I see the world in a different way than most teenagers do.”

Her mother, sitting beside her, beamed: “Obviously, she’s doing great. I feel very grateful.”

The book is a heartfelt, at times heartbreaking tale that, in the end, is much more about Sarah than the healthcare system. The book does not mention that very few children have benefited from expanded access to adult lungs. Of 24 children under 12 who have been granted “exceptions” and been wait-listed for adult lungs, only one besides Sarah wound up getting the organ from an adult, according to data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, which sets allocation policy.

Mostly, these tiny numbers reflect the fact that cutting down adult lungs is a last resort, said Stuart Sweet, a St. Louis Children’s Hospital pediatric lung transplant specialist and a past president of the network’s board.

Still, he said, the Murnaghans’ struggle raised legitimate questions about fairness that led OPTN to search for ways to better serve children. Two years ago, for example, the organisation changed the rules so that child lungs are offered to child candidates and then to adolescents within a 1,000-mile radius before adults are considered.

“Sarah’s case influenced and accelerated the thought process,” Sweet said.

He added, “I’m just so happy Sarah has done well. There is no question she has defied the odds.”

Janet said she wrote her book to offer hope and reassurance to other families.

“Our story is not unique,” she says in the book. “More than anything, we want to tell our story for the families who are out there fighting for survival. You are not alone. We see you.”

At 18 months, Sarah was diagnosed with a severe form of cystic fibrosis, a genetic defect that makes the body produce thick mucus. Janet became the manager of Sarah’s frequent hospitalisations, while husband Fran handled the home front. The couple have four younger children, including a daughter adopted from Ghana while Sarah was on the transplant waiting list, and a son who was born after the transplant.

Sarah was only 9 when the bacteria causing her chronic lung infections became resistant to antibiotics, forcing the decision to put her on the transplant list in December 2011.

A little more than a year later, she was admitted to CHOP. The book opens as her condition deteriorates, sending her to pediatric intensive care.

“I am upset and scared to move to the PICU, or as I call it, ‘the scary floor,’” Sarah says in a passage she and her mother wrote.

By then, the Murnaghans had twice been through “dry runs.” They were told pediatric lungs were available, but then something didn’t work out.

Janet assumed that Sarah’s increasingly dire situation would qualify her for the next available lungs, no matter the age of the donor. Janet was stunned to learn that the national allocation system required that before children under 12 could be considered for adult donor lungs, the organ had to be offered to all older patients on the waiting list first.

It was Janet’s sister, Sharon Ruddock, who began digging into OPTN data. Ruddock proposed a media blitz – capitalising on Janet’s experience as a former public relations executive – to tell the world about the age cutoff that, in the family’s view, was arbitrary, discriminatory, and deadly.

“Kids under 12 are dying at almost twice the rate as everyone else waiting for lungs,” Ruddock says in the book.

A 2014 review by Minnesota researchers, prompted by Sarah’s case, actually found no difference in transplant rates or death rates for lung transplant candidates ages 6 to 11 compared to older children and adults.

In any event, as the Murnaghans’ story exploded in the media — drawing support from the public and some politicians but disapproval from bioethicists and transplant experts — the family pleaded with the national Lung Review Board and then the US Department of Health and Human Services to bend the rule for Sarah. No luck.

Finally, the family went to federal court. The judge ordered the rule suspended. Seven days later, Sarah went into surgery at CHOP to receive a set of adult lungs.

What happened next was catastrophic. The lungs quickly failed. She was put on a heart-lung bypass machine to try to forestall her death.

“Sarah is sedated, intubated, unmoving, and – I fear – already gone,” Janet writes in the book. “It is impossible to believe that we could get the gift of life again after waiting 18 months to finally get the first set. We have not told anyone about the failure. This moment in time is indescribable — the level of pain and anguish, the sheer terror.”

Three days later, Sarah underwent a second double lung transplant — with an adult organ that normally would have been rejected because the donor had pneumonia.

“I have to resize the lungs anyway, so I won’t use that (infected) portion,” the surgeon told Janet. As Sarah finished eating her chicken tenders, she talked matter-of-factly about being, as she says at the end of the book, “mostly whole again.”

She occasionally has nightmares — a common reaction to prolonged intensive care — “but I haven’t had them that much in the past year.” She has profound hearing loss, a side effect of antibiotics, but a cochlear implant has partly restored hearing in one ear. She wears an insulin pump for her diabetes, another side effect of cystic fibrosis.

But she has had no problems with organ rejection — another way she has defied the odds.

Sarah’s admiration, however, is all for her mother.

“She’s a really good person,” Sarah said. “She should be proud of what she did.” — The Philadelphia Inquirer/TNS

“Our story is not unique. “More than anything, we want to tell our story for the families who are out there fighting for survival. You are not alone. We see you”

—Janet Murnaghan, author and mother of Sarah