Bloody, sentimental and shrewdly acted, The Sisters Brothers opens with a conspicuous bang and then clip-clops along a winding path, alternating between sibling-rivalry wisecracks and wry observations of a rapidly changing mid-19th century frontier full of startling new inventions. The toothbrush, for example. Or flush toilets. The way John C. Reilly regards such wonders, you’re reminded of just how good he can be doing the simplest things.

Reilly plays Eli Sisters, the naive, responsible one of the title duo. His alcoholic, dangerously touchy brother, Charlie, is portrayed by Joaquin Phoenix. “We’re good at what we do,” Charlie reminds Eli early on, by which time it’s already clear these siblings need a break – from their job, from their line of work, from the shadow cast by their drunken lout of a father.

The Sisters brothers kill for a living. The film’s opening nighttime ambush reveals their lack of finesse; strikingly photographed by cinematographer Benoit Debie, the melee leads to a burning barn, and in one bizarre, digitally realised detail, a horse on fire, galloping to his death. Nonetheless, they remain in the employ of a shadowy figure known only as the Commodore.

Their latest assignment requires them to hunt down a chemist (Riz Ahmed) who has discovered a way to locate gold in riverbeds all over the West. This miraculous invention poses a threat to the mining companies. Another man in the Commodore’s employ, an Eastern dandy (Jake Gyllenhaal), is sent on ahead of the Sisters boys to find and befriend the chemist until the killers arrive.

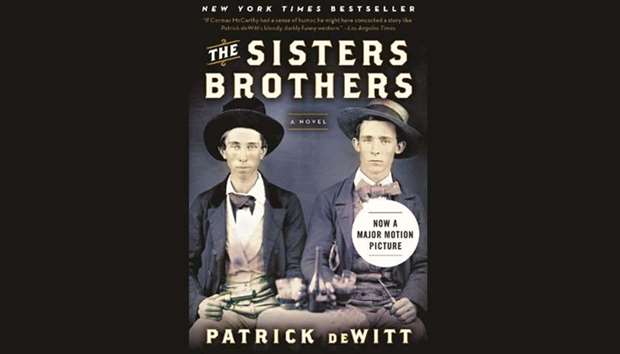

But the chemist’s idealistic talk of a shining utopian community intrigues the Gyllenhaal character, and by the time Reilly and Phoenix get there, The Sisters Brothers has turned into a series of best-laid plans gone astray. The material comes from a book by Canadian novelist Patrick DeWitt, and the film version marks the English-language debut of French director Jacques Audiard (A Prophet, Dheepan). He filmed this loping yarn, set in 1851 Oregon and California, against the landscapes of Romania and Spain. Quite deliberately, it all feels a little off-kilter. Nobody quite knows where they’re going in The Sisters Brothers, or how they’ll react to threats and enticements along the way.

Is Audiard’s movie a revisionist Western? I’m not sure that label means anything anymore. So much dark-hued, deromanticised mythology of the Old West has sprung up in long-form television in the advent of Deadwood, it’s misleading to characterise anything new as revisionist. It’s just as crazy to paint all John Ford Westerns as simple, black-and-white morality tales, or to lump an Anthony Mann creation such as The Naked Spur in with Howard Hawks’ Red River.

By the 1970s the Western genre had fallen into facetiousness and couldn’t get up. (That’s a generalisation, but I’ll go with it.) At its most antic, The Sisters Brothers recalls such ’70s follies as The Missouri Breaks in its reverence for creative actors given all the room in the world to establish a rapport. Reilly and Phoenix make for the best possible screen company under the material’s half-kidding, half-serious circumstances. These “saddlesore Sancho Panzas,” as Robbie Collin put it in the London Telegraph, also suggest a Wild West riff on Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, with Eli and Charlie wondering where they fit into the story pulling them forward. – Chicago Tribune/TNS