Natasha Ednan-Laperouse showed, in rare, tragic instances, these can

be fatal. How worried should parents be, wonders Emine Saner

‘Children are more likely to be affected — between 6 and 8% of children are thought to have food allergies, compared with less than 3% of adults — but numbers are growing in westernised countries, as well as places such as China’ — Holly Shaw, nurse adviser for Allergy UK

In July 2016, Natasha Ednan-Laperouse collapsed on a flight from London to Nice, suffering a fatal allergic reaction to a baguette bought from Pret a Manger. At an inquest, the court heard how Natasha, who was 15 and had multiple severe food allergies, had carefully checked the ingredients on the packet. Sesame seeds — which were in the bread dough, the family later found out — were not listed.

“It was their fault,” her father Nadim said in a statement. “I was stunned that a big food company like Pret could mislabel a sandwich and this could cause my daughter to die.”

This horrifying case highlights how careful people with allergies need to be, as do the food companies — not least because allergies have been growing in prevalence in the past few decades.

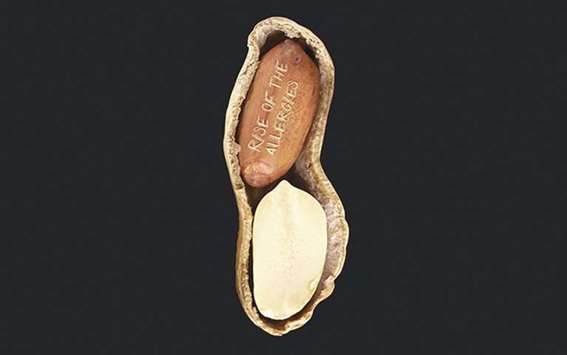

“Food allergy is on the rise and has been for some time,” says Holly Shaw, nurse adviser for Allergy UK, a charity that supports people with allergies. Children are more likely to be affected — between 6 and 8% of children are thought to have food allergies, compared with less than 3% of adults — but numbers are growing in westernised countries, as well as places such as China.

“Certainly, as a charity, we’ve seen an increase in the number of calls we receive, from adults and parents of children with suspected or confirmed allergy,” says Shaw. Certain types of allergy are more common in childhood, such as cow’s milk or egg allergy but, she says: “It is possible at any point in life to develop an allergy to something previously tolerated.”

Stephen Till, professor of allergy at King’s College London and a consultant allergist at Guy’s and St Thomas’ hospital trust, says that an allergic reaction occurs when your immune system inappropriately recognises something foreign as a bug, and mounts an attack against it. “You make antibodies which stick to your immune cells,” he says, “and when you get re-exposed at a later time to the allergen, those antibodies are already there and they trigger the immune cells to react.”

Allergies can have a huge impact on quality of life, and can, in rare cases such as that of Natasha Ednan-Laperouse, be fatal. There is no cure for a food allergy, although there has been recent promising work involving the use of probiotics and drug treatments. The first trial dedicated to treating adults with peanut allergy is just starting at Guy’s hospital.

“There is a lot of work going on in prevention to better understand the weaning process, and there’s a lot of buzz around desensitisation,” says Adam Fox, consultant paediatric allergist at Guy’s and St Thomas’ hospitals. Desensitisation is conducted by exposing the patient to minuscule, controlled amounts of the allergen. It’s an ongoing treatment though, rather than a cure. “When they stop having it regularly, they’re allergic again, it doesn’t change the underlying process.”

What we do know is that we are more allergic than ever. “If you think in terms of decades, are we seeing more food allergy now than we were 20 or 30 years ago? I think we can confidently say yes,” says Fox. “If you look at the research from the 1990s and early 2000s there is pretty good data that the amount of peanut allergy trebled in a very short period.”

There has also been an increase in the number of people with severe reactions showing up in hospital emergency departments. In 2015-16, 4,482 people in England were admitted to A&E for anaphylactic shock (although not all of these will have been down to food allergy). This number has been climbing each year and it’s the same across Europe, the US and Australia, says Fox.

Why is there this rise in allergies? The truth is, nobody knows. Fox doesn’t believe it is down to better diagnosis. And it won’t be down to one single thing. There have been suggestions that it could be caused by reasons ranging from a lack of vitamin D to gut health and pollution. Weaning practices could also influence food allergy, he says. “If you introduce something much earlier into the diet, then you’re less likely to become allergic to it,” he says. A 2008 study found that the prevalence of peanut allergy in Jewish children in the UK, where the advice had been to avoid peanuts, was 10 times higher than that of children in Israel, where rates are low — there, babies are often given peanut snacks.

Should parents wean their babies earlier, and introduce foods such as peanuts? Fox says it’s a “minefield”, but he advises sticking to the Department of Health and World Health Organisation’s line that promotes exclusive breastfeeding for six months before introducing other foods, “and to not delay the introduction of allergenic foods such as peanut and egg beyond that, as this may increase the risk of allergy, particularly in kids with eczema”. (Fox says there is a direct relationship between a baby having eczema and the chances of them having a food allergy.)

The adults Till sees are those whose allergies started in childhood (people are more likely to grow out of milk or egg allergies, than peanut allergies, for instance) or those with allergy that started in adolescence or adulthood. Again, it is not clear why you can tolerate something all your life and then develop an allergy to it. It could be to do with our changing diets in recent decades.

“The commonest new onset severe food allergy I see is to shellfish, and particularly prawns,” says Till. “It’s my own observation that the types of food we eat has changed quite a lot in recent decades as a result of changes in the food industry and supply chain.” He says we are now eating foods such as tiger prawns that we probably didn’t eat so often in the past.

He has started to see people with an allergy to lupin flour, which comes from a legume in the same family as peanuts, which is more commonly used in continental Europe but has been increasingly used in the UK. Sesame — thought to have been the cause of Natasha Ednan-Laperouse’s reaction — is another growing allergen, thanks to its inclusion in products that are now mainstream, such as hummus. One problem with sesame, says Till, is: “It often doesn’t show up very well in our tests, so it can be difficult to gauge just how allergic someone is to it.”

Fox says it’s important to stress that deaths from food allergy are still rare. “Food allergy is not the leading cause of death of people with food allergies— it’s still a very remote risk,” says Fox. “But of course you don’t want to be that one who is incredibly unlucky, so it causes great anxiety. The real challenge of managing kids with food allergy is it’s really hard to predict which of the children are going to have the bad reactions, so everybody has to behave as if they might be that one.” — The Guardian

Adam Fox, consultant paediatric allergist, advises sticking to the Department of Health and World Health Organisation’s line that promotes exclusive breastfeeding for six months before introducing other foods, “and to not delay the introduction of allergenic foods such as peanut and egg beyond that, as this may increase the risk of allergy, particularly in kids with eczema”

FINDING:“If you look at the research from the 1990s and early 2000s there is pretty good data that the amount of peanut allergy trebled in a very short period,” says Adam Fox, consultant paediatric allergist at Guy’s and St Thomas’ hospitals