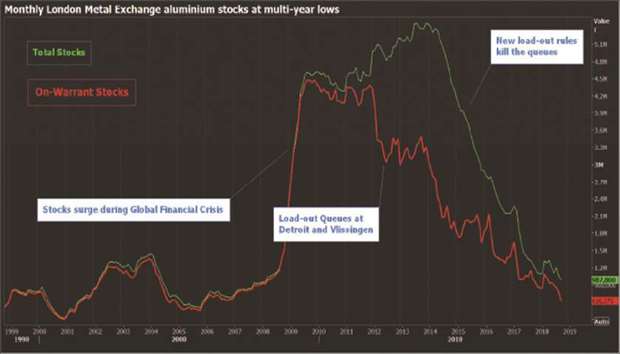

London Metal Exchange (LME) on-warrant aluminium stocks, metal not earmarked for delivery, are at their lowest since January 2006 at 608,050 tonnes — a far cry from the peaks hit over 2010-14.

Appearances, however, can be deceptive. There is a strong suspicion that erosion of LME inventory is as much to do with the exchange’s warehousing function as with market reality.

Exchange stocks of any commodity are only ever part of the bigger inventory picture.

When LME aluminium stocks exploded in 2009, it was partly down to the immediate impact of slumping demand but also to the squeeze on credit, which forced those holding off-market inventory to deliver to the market of last resort.

And when those infamous load-out queues emerged at Detroit and the Dutch port of Vlissingen over the course of 2012-2014, the metal wasn’t going to a consumer but back to cheaper off-market storage. The exchange’s multiple measures to deal with those queues simply accelerated a mass relocation of metal to the statistical shadows.

All of which makes it impossible to say with any certainty exactly how much inventory the aluminium market has been carrying. There are as many estimates as there are analysts.

But it is this metal, not LME-stored metal, that is the market of first resort for the physical supply chain. It is being eroded, but there is no evidence yet of an availability crisis. The LME three-month price, currently trading at $2,090 a tonne, is down 7.5% from the start of 2018. Physical premiums are still unwinding from their post-sanctions highs.

Fourth-quarter shipments to Japan, a benchmark for the Asian region, has just settled at $103 a tonne over LME cash metal, down from $132 in the third quarter. As one Japanese buyer told Reuters: “Producers made a compromise to come down as there were no feelings of supply tightness.”

Rather than signalling a squeeze on aluminium, the scale of decline in LME inventory may be signalling a squeeze on its warehousing companies.

The cumulative effect of the LME’s queue-killing rule changes, particularly the cap on rents and faster load-out requirements, has been to reduce their ability to incentivise metal into their sheds.

And a good thing, too, many physical aluminium players will say. The guaranteed income from long load-out queues allowed warehouse companies to outbid the physical market for fresh units. With no structural load-out queues and this year’s elevated physical premiums, they cannot compete.

That’s a problem for those entities specialising in LME storage — witness the collapse of Worldwide Warehouse Solutions last July. Warehouse operators have even lobbied for the exchange to relax its rules to allow longer queues; a suggestion that provoked outrage when it was floated past the exchange’s users committee.

In truth, warehouse operators may have only themselves to blame for the accelerated departure of aluminium from the LME system. After the exchange broke the old queue model of warehouse revenue, operators evolved ever more ingenious ways to attract metal. One in particular, rent-sharing, may be behind moves out of LME storage.

A “lifetime” incentive allows someone delivering physical metal onto LME warrant and then selling it to receive a share of the warehousing rental until such time as the warrant is eventually cancelled by a new owner. This not only limits the ability of the new owners to negotiate their own rental deals but raises uncomfortable questions about the flow of information between the warehouse operator and original seller with whom the rent is being split. Concerns about such “back-ended” incentives led the exchange to issue a reminder in October 2016 that “the LME expects warehouses to maintain the confidentiality of information it holds on the stock of metal under warrant.” Many market participants are unconvinced, opting for the easier solution of cancelling their metal and moving it out of LME storage as soon as they can.

These new warehousing and stocks dynamics should not come as any surprise.

The LME itself accepted in its “Strategic Pathway” document of September 2017 that the result of its rule changes would mean that “less metal would be expected to reside in the LME system”.

“Indeed, this has been the experience of the market; stocks of metal in queued warehouses (...) have fallen significantly, and the outflowing metal has broadly not been re-absorbed into the LME system, given the inability of any other operator to pay a suitable incentive in the post-queues environment,” the report said. In many ways we’re returning to the status quo that existed prior to 2008, when LME stocks were generally much lower than the amount of shadow inventory sitting off-market.

Given the right market incentive, as opposed to warehouser incentive, the metal will reappear when it is needed. That much was clear in February, April and July this year, when tight time-spreads acted to draw aluminium back into the LME system.

* Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are those of the author.