The wider cinchona species is used in the production of the anti-malaria medicine, quinine.

But experts say the cinchona tree is in danger of extinction due to government neglect, while many Peruvians can no longer tell it apart from fig trees or quinoa plants.

“Peru has 20 of the world’s 29 cinchona species but already many of them are hard to find due to deforestation, degradation of the soil and the growth of agriculture,” forest engineer Alejandro Gomez told AFP.

“Their habitat is very fragile and they are exposed to extermination due to the burning of large areas of land to grow coffee and other crops, and also for the quality of their wood,” added Gomez, who is managing a preservation project.

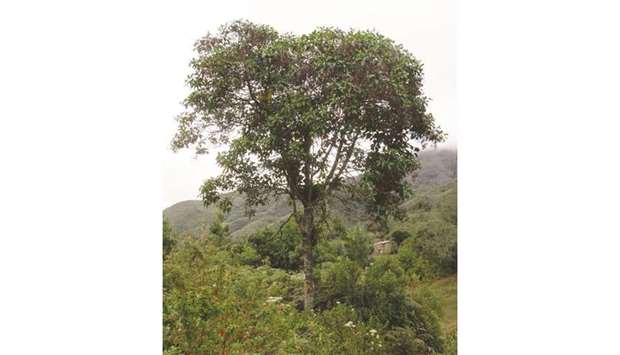

Cinchona trees grow up to 15m in height, in humid forests between 1,300m and 2,900m above sea level, mostly in the north west but also the centre of Peru.

It was first used for medicinal purposes by the pre-Columbian peoples of Peru, Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela to treat fever and pain, but now cinchona is also used in the production of tonic water and angostura bitter, an alcoholic beverage used in Peru’s national cocktail, pisco sour.

According to Jose Luis Marcelo, professor at the National Agrarian University, “six cinchonas that grow only in Peru and containing a high concentration of quinine, are under threat of disappearing.”

The National History Museum at the National University of San Marcos says there are only 500-600 of the ‘Cinchona officinalis’ species, or colourless bark, left in the country.

Specialists have been asking both the central and local governments for help in protecting the trees, but without success.

Marcelo says the Agrarian University has the teams of specialists necessary to “restore this icon of the national coat of arms, but funding is needed.”

Education may also be needed simply to teach Peruvians the difference between the cinchona and fig tree.

On some flags sold in shops ahead of national holidays, researcher Roque Rodriguez has found a picture of the fig tree rather than a cinchona.

The fact that flag makers can’t tell the difference between the two plants “shows the ignorance” of Peruvians when it comes to their national tree, Rodriguez, who is trying to clone the cinchona in order to help reintroduce it throughout the country, told AFP.

Back in 2008, Peru’s congress approved a law declaring various wild species of flora as natural heritage but the text described quinoa as Cinchona officinalis.

But quinoa is a cereal, not a tree like cinchona, says Rodriguez.

While the current Peruvian government may not value the cinchona, its bark was much sought after in Europe once it was brought to the old continent in 1631 by a Jesuit priest.

There it was used to treat scrapie, a fatal disease affecting sheep and goats, and cinchona species have since been planted outside of South America.

The species was named after the countess of Chinchon, after her life was saved by its bark.

Bolivar and the nascent Peruvian Congress then decided in 1825, soon after independence from Spain, to include the cinchona in the coat of arms as recognition of its medicinal benefits.